You don’t need more ‘me-time’, you need to do your job better

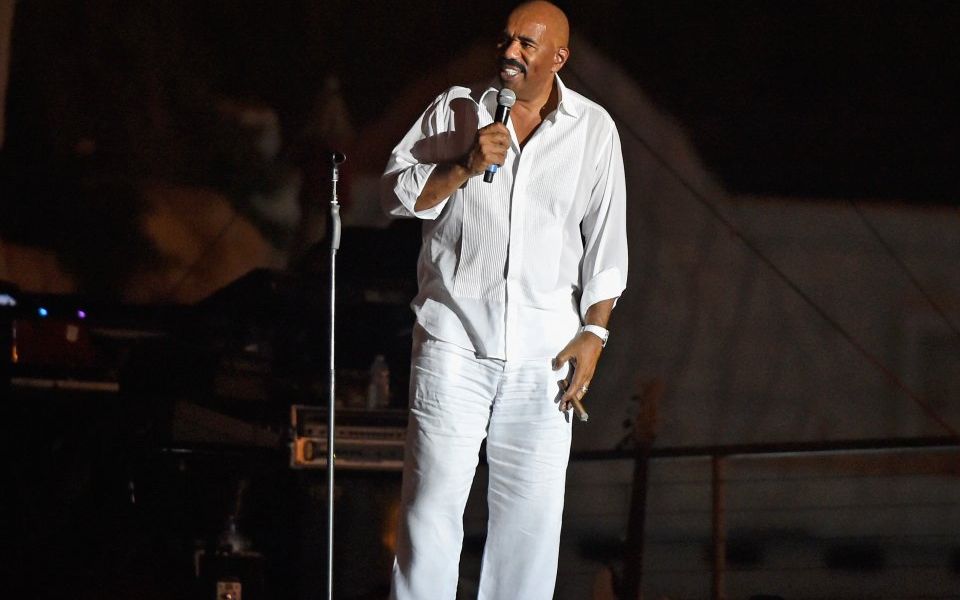

Have you seen a memo that Steve Harvey, the star comedian and host of the eponymous US talk show, had sent to his studio staff?

If you have not, you should. The memo, leaked to a blogger last week, outlines the rules of staff conduct on set.

“Do not wait in any hallway to speak to me. I hate being ambushed. Please make an appointment,” it says.

Also: “I am seeking more free time for me throughout the day.”

Or this, my favourite: “My security team will stop everyone from standing at my door who has the intent to see or speak to me”.

As staff memos go, this one is certifiable. At the same time, I can’t say that I do not share Harvey’s sentiment.

Colleagues are generally distracting. Often annoying. When I worked in an office, my ideal day would have been to draft for a few hours behind the closed doors, then take a short scheduled meeting, then wrap up and go home after a highly productive morning.

Like Harvey, I would hope that no one would “ambush” me in the hallways, so that I would not have to do chit-chat and ask them how their weekend was. Because most of the time, I wouldn’t be remotely interested.

Now that I work for myself, this is exactly how my day is like.

But Harvey is a different story, as he actually works in an office. And no matter how critical his personal input, he is really just a speck in a gigantic effort that delivers his show.

“You have obviously never worked on set”, a Harvey defendant tweeted, implying that top on-air talent needs protection from over-eager employees.

I have, actually. In the early nineties, I did an internship with Peter Jennings, the legendary anchor for ABC World News Tonight. Broadcasting in the golden age of the US network news, Jennings was one of its all-time greats, up there with Edward Murrow and Walter Cronkite – and in terms of power and celebrity, could match Harvey viewer for viewer, fan for fan.

Apart from the sheer drive and energy that took to prepare his broadcasts, Jennings’s work required faultless spontaneity. Things changed constantly: news happened, guests cancelled, leads went cold, footage got lost, scripts got re-written. The set was not a place for protocols or scheduled appointments: staff needed access to the anchor in real time.

When Jennings was writing or interviewing, he closed his office door and no one dared enter. When he finished, he opened the door and a flood of producers, reporters, researchers, assistants poured in. If they had something worthwhile to say, they got Jennings’s attention. If not, they were dismissed quickly and cheerfully. The system worked very well.

Jennings knew that being “ambushed” by colleagues was part of the deal. Not in his wildest dreams would he think of the newsroom as a place for “me-time”.

If Harvey’s staff are really ambushing him – as in chasing after him in the corridors asking to give their cousin a job – he should fire them. If they are approaching him with questions about the show, but he finds these so irrelevant that he feels harassed, he should also fire them and instead hire a team whose opinions he respects.

But if we assume that Harvey’s staff are reasonable professionals who need access to him during the day to prepare his programme, then he is really in the wrong. And instead of holing up in his dressing room and sending out crazy memos, he should try to become – as we like to say in the trade – a team player.