Innovation Diary: Three things we can learn from the high growth small business gazelles

OVER 350,000 new firms have been launched in the UK this year, and confidence is rising. Aldermore Bank research, released on Friday, saw small to medium-sized enterprise (SME) confidence in the economy climb for the fourth consecutive quarter.

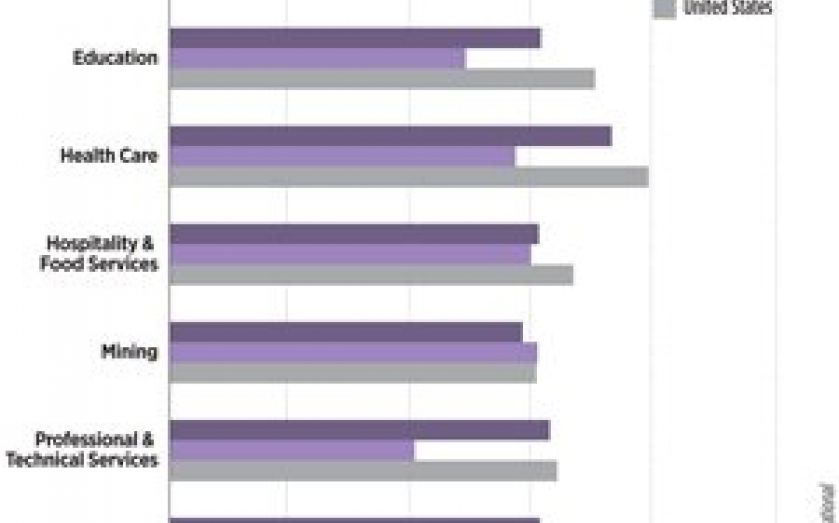

Yet this tells us little about what it takes to succeed as a UK startup. As Mark Hart of Aston Business School wrote in City A.M. earlier this year, it’s normal for a quarter of a million businesses to start up annually, but 70 to 80 per cent will be gone within 10 years. And the UK may be worse at this than others. RSM International has found that UK firms born in 2008 were less likely to survive to 2011 than their US or Australian counterparts in a range of industries. Just 40 per cent of 2008 UK startups in professional services still traded in 2011, for instance. And the trend won’t necessarily end with the economic upswing. Aldermore notes that SME insolvencies rose by 14.1 per cent between the second and first quarters of 2013.

Meanwhile, Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses UK research discovered that just 1 per cent of companies (high growth SMEs) were responsible for 23 per cent of new employment between 2007 and 2010. What can we learn from the growth gazelles? Here are three ideas.

AVOID LIFESTYLE BUSINESSES

Mark Doleman, head of entrepreneurial business at Deloitte, suggests a distinction between two types of startups. “Lifestyle” firms, he says, are not entrepreneurial. Typically founded out of necessity, they make tiny margins and profit by keeping overheads low. He cites estate agency. Even if the market is expanding and you set up an agency, you may struggle to become a big cheese without a fresh angle. And you must be seriously determined to disrupt. Zoopla (now considering a £1.3bn listing) is the real innovator. Such companies “won’t accept the status quo,” says Doleman.

Yet the line between lifestyle and growth firms is not always distinct. As Doleman says, “it’s hard to define the spark” that differentiates a success from a jobsworth. Julie Deane of the Cambridge Satchel Company, started her leather goods firm in 2008 to pay her daughter’s school fees – out of necessity. Yet her turnover quickly rose to £8m by 2011. Why? She brazenly marketed her product to a range of fashion editors, for instance. But Doleman thinks it’s down to vision. Deane probably thought “on a bigger scale” to just another bag maker. “That vision is the starting point,” he says.

LEVERAGE TECHNOLOGY AND OTHERS

Yet Doleman acknowledges that “technology makes it easier to do.” With advances in online shopping and small-scale low cost production, “good quality lifestyle companies could become high growth.” Many product-based or service businesses can sell globally and at low cost over marketplaces like Etsy or business-to-business platforms like Blur.

Alternatively, Hart’s research has shown the value of mentoring and professional help. Among the participants of a training programme he is involved in, 69 per cent thought formal training had enhanced their prospects of winning finance, while 83 per cent said they understood the investment options better. “Contacts and intelligence are two of the most important currencies for all companies. But particularly for those looking to grow,” he says.

CHOOSE SERVICES, NOT PRODUCTS

As Peter Lawrence, author of Enterprise in Action, has said, “The mature economies of the West seem inhospitable to entrepreneurial penetration.” High competition, saturated markets, and big business dominance look like near impossible road blocks. Yet flip this view on its head, and sophisticated markets are full of opportunities for doing old things better. But he notes that, in this sphere, “business creation has been decoupled from product innovation.” In short, the bulk of the most innovative companies are in services – able to access large company supply chains in an imaginative way.

Tom Welsh is business features editor at City A.M.