Political risks rising in the Eurozone

The rise of populist parties across the bloc and high unemployment may lead to more market volatility, writes Liam Ward-Proud

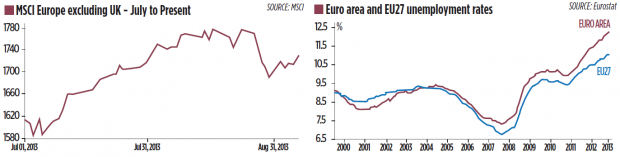

RECOVERY in the Eurozone is certainly underway. The region ended its 18-month recession in the second quarter, posting growth of 0.3 per cent. European equities, despite a few blips, have also performed strongly, with the MSCI Europe index (excluding the UK, see graph) rising from lows close to 1,547 at the end of June to its current level of 1,729. Moreover, the euro has strengthened against major currencies in the past six months, moving above $1.326 and ¥132.14 yesterday, compared to the less than $1.30 and ¥125 at the beginning of March.

Despite these encouraging economic indicators, some see the signs of deep-rooted political risks re-awakening across the bloc. “The political situation in the Eurozone remains highly precarious,” says Joe Rundle of ETX Capital. Former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi has threatened to bring down the country’s coalition government if a senate committee decides to ban him from parliament. The precise outcome of Germany’s 22 September election remains uncertain – even if Angela Merkel stands to be re-elected. And the unresolved issue of further financial assistance for Greece and continued austerity in the peripheral economies means “political instability will come back to haunt us again and again,” says Rundle .

ITALIAN CRISIS

Barclays Capital’s Fabio Fois said in a recent note that a further escalation of the Italian political crisis could “lead to political paralysis,” halting the country’s crucial economic reforms and potentially denting the Italian FTSE MIB Index. The index fell from its August highs of over 17,677 to the current level of around 17,000 amid the tensions.

Worryingly, Benedetto della Vedova, a member of the committee deciding on Berlusconi’s ban, recently said that “the decision could take weeks not days.” Such protracted uncertainty, according to Michael Hewson of CMC Markets, “distracts from the absolutely vital issue of long-term structural reform in Italy”. The nation’s public debt stands at over €2 trillion (£1.68 trillion), and is second only to Greece in the Eurozone as a percentage of GDP. Despite budget cuts and tax hikes implemented by the government of Mario Monti between November 2011 and April this year, Italy’s public debt rose by €600m in June compared to May, according to the latest figures from the Bank of Italy.

Deutsche Bank’s Gilles Moec says that “we have not seen anywhere near enough progress on reforms in Italy”. Moec points out that the situation is “very fragile”, but the real danger is that it detracts from further action to restore the public finances.

GERMAN ELECTIONS

Chancellor Angela Merkel’s coalition government (composed of the Christian Democrats and the liberal Free Democrats, their junior partners) looks set to be re-elected. But Schroders’s Europe economist Azad Zangana sees “increased political risk and market volatility” as likely in the aftermath of the elections.

According to Zangana, the German election itself is “unlikely to yield a result that will immediately change the outlook for the Eurozone”, but the increased influence of the rival Social Democrats (SDP) could mean “a tougher stance on banks”. In an attempt to win votes from the SDP, Merkel’s coalition has announced plans for wealth taxes, levies on banks and financial transaction taxes, which will hurt financial institutions and investors, Zangana says.

Ladbrokes, in association with The Election Game, yesterday had the current coalition of Christian Democrats and Free Democrats as odds-on favourite to form a government, at 4/6. But they say they are “reluctant to write off SDP involvement in government”, and yesterday offered 2/1 on a coalition between the socialists and Merkel’s Christian Democrats.

Hewson highlights the candidates’ reluctance to address Greece’s funding needs. “The idea of a haircut for holders of Greek debt is politically toxic, and the lack of serious debate on the issue is worrying.” The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has estimated that a third package for Greece of around €11bn will be necessary, but Merkel refuses to be drawn on the issue. The Chancellor’s ambiguous stance, according to Hewson, “conflicts with the IMF, and sets them up for a potential standoff in November.”

The possibility of a disunited Troika, with Merkel under pressure from a German public tired of bailouts, could prove destabilising for markets, and will hurt Greece’s chances of recovery, he says.

DEEP TENSIONS

Beyond these immediate concerns, Rundle thinks that the political implications of austerity may not have entirely played out yet. “Remember that the peripheral economies (Greece, Spain and Portugal among others) will stay in a recession for some time.” Eurozone second quarter GDP growth was low at 0.3 per cent, and this was driven mainly by the core countries of Germany and France.

The peripheral economies are not showing convincing signs of recovery, with Greece yesterday posting an 8.1 per cent year-on-year fall in industrial production for July, while Spain and Italy’s GDP both shrank in the second quarter.

Rundle suggests that the combination of low growth, high unemployment (see graph above) and fiscal contraction risks stoking anti-EU sentiment across the bloc. “There will likely come a point when austerity becomes so painful for these nations that a minister resigns,” he says. When the Portuguese government looked close to collapse at the beginning of July, the country’s PS120 stock index fell by over 5 per cent, and the euro fell from around $1.30 to the $1.28 mark.

“We have already seen fringe anti-euro parties gain influence in the polls,” Rundle notes. Syriza and the Five Star Movement have gained traction in Greece and Italy respectively, while Germany’s Alternative for Deutschland party, while lagging in the polls, opposes the funding of debts for financially weaker nations. According to a May poll, in France, the eurosceptic leader of the Front Nationale Marine Le Pen would have unseated incumbent Francois Hollande if a Presidential election had been held that day.

“The political sustainability of the core countries supporting struggling ones remains unclear,” Rundle says. This may be especially concerning when the signs of growth between Germany and the rest of Europe are so different. Purchasing Managers’s Index figures for Germany in August were 53.5, compared to figures below 50 (signalling contraction) for Greece, Spain, Italy and even France.

THE GRAND BARGAIN

But Christian Schulz of Berenberg Bank says that this two-tier support system is how the Eurozone has always operated. “The grand bargain in the Eurozone is that the strong countries support the weak, but the weak accept conditions,” he says. Germany and France “do not want to waste their money on shaky crisis countries. But they also do not want the enormous political and economic crisis that would come if the euro were to break up.”

Deutsche Bank’s Moec, meanwhile, argues that “growth has come at a very good time in terms of political attitudes to the EU. If we were seeing a much higher unemployment rate, and the region as a whole was still contracting, the danger of populist policies and civil unrest would be much higher.” As long as there are no surprises in the German elections, Moec says, “hopefully we’ll be in for a quiet Autumn.”

Schulz says that the unemployment rate across the Eurozone is key. “The faster unemployment starts falling,” he says, “the faster some of these political risks will recede.” Given that the jobless rate remains at 27.6 per cent in Greece, and 26.3 per cent in Spain (with youth unemployment close to 65 per cent in the former according to the latest figures), the prospect of political instability derailing the Eurozone recovery will not disappear any time soon .