| Updated:

It’s a mistake to take Pareto’s 80/20 law too literally

The Pareto principle is a rough rule of thumb, not a silver bullet.

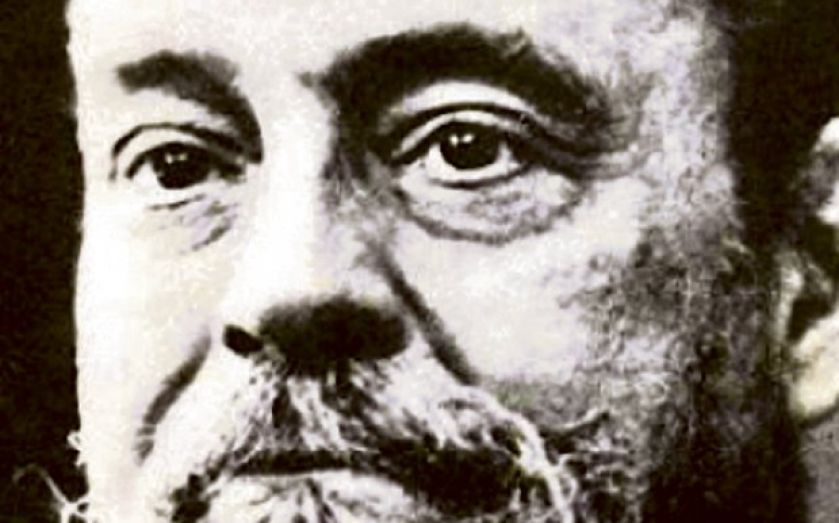

Business books tend to be full of seductively simple rules for achieving success. But few have proved as enduring as the 80/20 law (or the Pareto principle, after Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian engineer and economist who provided the germ for the idea in 1906).

Pareto noticed that around 80 per cent of land in Italy was owned by roughly 20 per cent of the population, and that 80 per cent of the peas in his garden grew from just 20 per cent of the pea pods.

Decades later, US management consultant Joseph Juran would repurpose the idea for businesses. He argued that 80 per cent of production defects, for example, are typically caused by just 20 per cent of potential causes, or that 80 per cent of sales come from 20 per cent of customers. Managers should focus on the “vital few”, not the “trivial many”. More recently, career development writers have revived the idea in the popular imagination, with bestselling author Timothy Ferriss using it in his guide to achieving the elusive “four-hour work week”. But is the principle the panacea so many claim?

AN EMPTY SLOGAN?

The rule has certainly come in for its share of criticism. Used as a productivity tool (focus your efforts on the 20 per cent of emails that relate to the majority of your outputs at work, for example), it’s been accused of vacuousness. “Spend time on important things” doesn’t exactly constitute useful advice in itself. How to go about identifying the activities that account for 80 per cent of outputs? As Lifehack’s Dustin Wax asks, “What would ‘80 per cent’ of my productivity even look like?”

Others have associated the 80/20 principle with a tendency towards myopia. In the wake of the magnitude nine earthquake that struck Japan in 2011 (triggering the disaster at Fukushima nuclear power station), companies using the 80/20 rule to manage supply chains were severely disrupted. Writing in the Disaster Recovery Journal, supply chain expert Patrick Brennan said the typical supply chain risk programme looked only at the 20 per cent of suppliers that made up around 80 per cent of supply chain spend.

Only when disaster struck did they realise that among the 80 per cent of less important suppliers were functions that could halt the whole chain. “When the lack of availability of a $1 part prevents a company from making a $30,000 product, something needs to change,” wrote Brennan. In a similar vein, Juran eventually came to soften his phrase “the trivial many” to “the useful many”, referring to the 80 per cent of less crucial tasks.

A HELPFUL STARTING POINT

Pareto’s modern disciples, however, reply that many of these problems stem from poor implementation or misunderstanding, rather than a flawed concept. Andre Kibbe of Work Awesome argues that a common stumbling block is taking the principle too literally. The rule is really just a “fancy way of saying that a few elements in a set have a lot more leverage than most elements,” he says. The crucial tasks could just as easily be 20, 10, 5 or even 1 per cent of your activities – getting wrapped up in the specifics misses the point.

Instead, it might be better to think of the Pareto principle as a rough “filtering mechanism”. In the modern office, it’s all too easy to get overwhelmed by trivial tasks. The 80/20 rule just reminds us that some are far more consequential than others.

Make mind mapping easy

MindNode

£2.99

£2.99

Mind mapping has come in for a lot of criticism in recent years, with scores of educational psychologists calling its touted benefits into question. But for those who still like to have a visual representation of the connections between their ideas, MindNode is an awful lot easier than scribbling all over a sheet of A3 paper. Start with a central thought, and then slowly build up from there. And the app’s software will handle the layout, so you don’t need to worry about running out of space.