COP21 Paris climate summit: Here are four things you need to know about climate change, from the global economic impact to fossil fuel subsidies

World leaders are sitting down for a second day of talks in Paris, hoping to secure a strong deal at what has been billed as the most important climate summit for years.

The eyes of the world are trained on the outcome, with hundreds of thousands marching worldwide on Sunday to demand stronger action on climate change.

What will come from the Paris talks is still unknown, of course, but whether increased financial aid to poorer countries likely to be more ravaged by rising temperatures or the holy grail of a global emissions trading scheme, answers will become clearer over the conference’s remaining ten days.

Here are four things we already know about climate change.

1. The global economy is set to shrink by a quarter

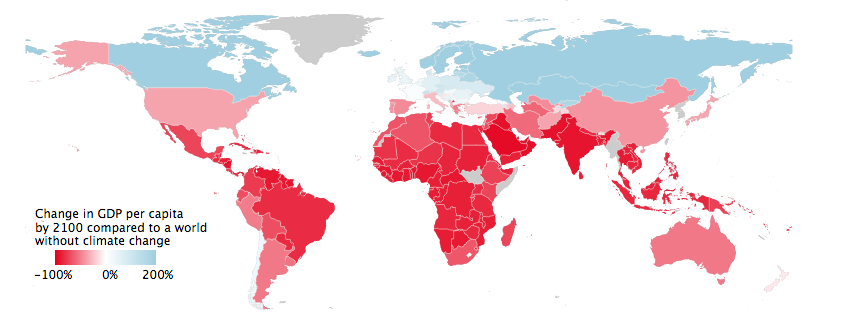

The financial impact of climate change is enormous – and is set to widen global inequality, as it hits poorer countries disproportionately hard.

A recent study by Berkeley researchers found people living in the poorest 40 per cent of countries will have a 75 per cent reduction in income by 2100, while the richest 20 per cent might have slight gains.

(A very few already rich countries, like Scandinavia, Canada and Russia, could actually benefit economically, as the warming climate opens up new opportunities, for instance in mining.)

The world’s richest countries pledged $100bn in financial aid by 2020 at previous summits in Copenhagen and Cancún, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, US President Barack Obama and UK PM David Cameron are among those who’ve promised to make further support to poorer countries a priority at the negotiating table this year.

2. Nearly 180 countries have pledged to bring their emissions down

Countries have been putting together their individual emission reduction promises ahead of Paris. Some 178 have submitted Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs).

This is seen by many as reason for optimism: there is a near-universal will to have a strong deal come out of Paris, and not just from politicians. UK business has thrown its weight behind an “ambitious, lasting deal”, and interest is high among the general public, with hundreds of thousands joining Sunday’s global climate marches.

Green Energy boss Juliet Davenport wrote in City A.M. yesterday:

This time, we will see ambition, agreement and a collective push towards the action we so desperately need.

The question is, will this be enough? The collective pledges so far put global greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 at 55-60bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. This is lower than the 68bn tonnes the UN has predicted we’ll emit by remaining at status quo – but still far from the 50bn (or lower) goal needed if we hope to avoid a warming of two degrees.

And speaking of that…

3. The magic two-degree goal is probably already out of reach

The Earth is already 1.7 degrees Celsius warmer than pre-industrial temperatures. Two degrees warming is seen as the crucial limit if we’re to avoid some of the worst consequences of climate change.

But many scientists believe we’re already there.

The chart above comes from a recent paper by Robert Jackson, Pierre Friedlingstein, Josep Canadell, and Robbie Andrew. The researchers from Stanford University suggest we’re rapidly running out of time:

Without immediate and substantial mitigation […] time has nearly run out for two-degree mitigation.

4. We spent $5 trillion subsidising fossil fuels in 2015

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggests global fossil fuel subsidies will hit $5 trillion before the year is out, with the cost of local air pollution and climate change accounting for three-quarters of the cost.

This sends the real cost of using coal skyrocketing to more than $200 per tonne (…and you thought renewables were the expensive option…).

Economists and climate change experts like Nicholas Stern and Amar Battacharya agree that getting rid of these subsidies is key to developing sustainable infrastructure:

Paris can set the course for bolder actions on the elimination of fossil fuel subsidies and the wider and faster adoption of carbon pricing that together fundamentally distort investment choices and have such a deleterious impact on health and well-being.