Are UK markets overstretched?

With the FTSE 100 and All-Share a wee bit below their all-time highs and valuations above average, many fear equities are too high and will soon fall. However, in our view, such worries are misplaced. Valuations aren’t predictive, and markets routinely set all-time highs during bull markets. We expect UK markets to keep making chart-topping records for the foreseeable future.

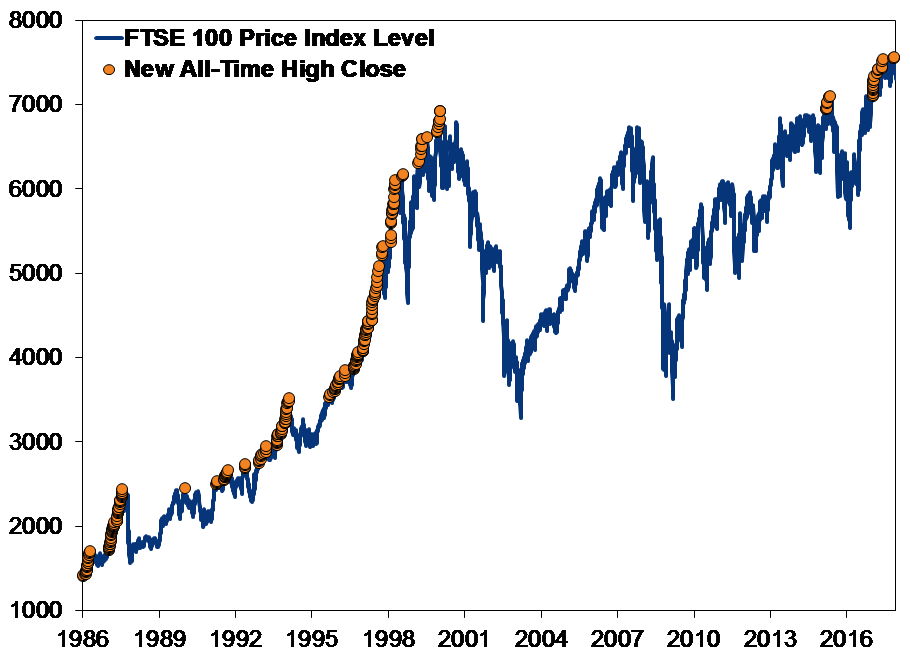

New highs are normal in a bull market. 6 November’s record high was the 32nd since the FTSE 100’s 2009 bottom. We could easily see many more before bull’s end. In the 11/10/1990 through 18/9/2000 global bull market, there were 189, but between then and now there was a 15-year stretch without record highs[i] (Exhibit 1). Perhaps that’s why they seem novel now! The FTSE 100 Price Index peaked before world markets, on 30/12/1999, and never regained that high during the 2003 – 2007 bull, which we believe ended prematurely tied to US financial accounting rule shifts and the government’s inconsistent crisis response. Investors didn’t see new record highs until 2015, but only nine occurred that year before a global correction struck midyear. The rally resumed the following February, and by autumn, the FTSE was regularly notching new highs. Still, the coincidence of a correction beginning soon after the FTSE regained record heights may reinforce investors’ acrophobia.

Exhibit 1: After a 15-Year Stretch, New Highs Resume

Source: FactSet, as of 5/12/2017. FTSE 100 price index, 2/1/1986 – 4/12/2017

But it is mere coincidence—equities often set dozens of new highs during a bull market—sometimes hundreds. Take the US’s S&P 500 for example. Across the pond, up until 4 December, the S&P 500 Total Return Index has set 247 all-time highs during this bull market.[ii]In the 1990s, history’s longest-running bull, it notched 345.[iii] Nothing about the UK’s underlying business dynamism or market fundamentals suggests the FTSE is incapable of matching—or surpassing—these feats.

Old age and record highs don’t kill bull markets. Yes, one record high will eventually be this bull’s peak, but it is impossible to identify in real time. As bear markets roll over slowly, peaks usually aren’t apparent until a few months after the fact. We believe investors who avoid shares because of record highs alone risk missing out on considerable future gains.

The same goes for those who shun equities due to above-average price-to-earnings ratios, in our view. Valuations aren’t predictive. Cheap shares can get cheaper and expensive shares more expensive. P/Es are often sky-high very early in bull markets, as share prices recover before earnings do. Sentiment also influences P/E ratios during a bull. Valuations are usually lower, during younger bulls, when investors have less optimism about future earnings. As bulls mature and investors gain confidence, becoming willing to pay up for earnings P/Es usually rise, but in the UK, we’ve seen markets rising lately against a backdrop of falling P/Es. Although the FTSE 100’s P/E of 21.5 exceeds the historical average of about 15, much of this is tied to matters that are largely behind us.

Falling oil and commodity prices weighed on UK Materials and Energy firms’ earnings for much of the last few years. These sectors represent 24 per cent of the index by market cap. That drove the FTSE 100’s P/E to just over 40 in August 2016. Since then, as earnings in those sectors have begun recovering (and UK banks have largely moved past some large ad hoc regulatory charges that depressed earnings in recent years), P/Es are down by nearly half. Over the same span, UK markets are up 6.5 per cent, notching 23 all-time highs.[iv] Consider this back story, and valuations aren’t as extreme as they’re sometimes made out to be. Either way, even higher valuations didn’t foretell trouble in the last year—highlighting the fact they just don’t predict equities’ direction.

Bulls end by fundamentals deteriorating relative to expectations. This generally comes in one of two varieties—the “wall” or the “wallop.” Equities stop climbing the “wall of worry” when sentiment becomes so euphoric reality can’t possibly meet expectations. The late-1990’s US dot-com bubble was the last prominent example in equity markets. At the top, “new-economy” thinking dominates. During the frenzy, low-quality IPOs—firms without any rational business model and earnings potential—launch to great fanfare. Folks expect them to usher in a paradigm-shifting era of continuous growth, abolishing the business cycle. When the new era fails to materialise, demand for shares dries up, leaving a supply glut, and prices crash. Today, rather than celebrate record highs, financial media use the occasion to warn about downside risks. This is a sign equities still have more “wall of worry” to climb.

Bears can also begin when a huge, unseen negative truncates an expansion before it runs its natural course. To move the needle, it likely must be large enough to render recession globally—a couple of trillion pounds or so. Owing to the UK’s strong global economic and capital markets links, it generally doesn’t diverge from the world much. For the UK to get a bear whilst the world is in a bull would be unusual. 2008’s global financial crisis was a wallop. So was Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia, which forced markets to price in the onset of World War II in 1938, cutting short what we believe was a nascent bull market. We don’t see anything of that magnitude today. Today’s fears are either too small, too widely known or false.

If a wall or wallop were to occur, we would only know it after the fact. Until then, however, trying to call a top and preemptively avoid it carries greater risk for investors. If wrong, you’ll be missing out on upside that can potentially be more damaging to your portfolio’s long-term returns than any prospective bear.

Investing in equity markets involves the risk of loss and there is no guarantee that all or any capital invested will be repaid. Past performance neither guarantees nor reliably indicates future performance. The value of investments and the income from them will fluctuate with world equity markets and international currency exchange rates.

Fisher Investments Europe Limited, trading as Fisher Investments UK, is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA Number 191609) and is registered in England (Company Number 3850593). Fisher Investments Europe Limited Headquarters: 2nd Floor, 6-10 Whitfield Street, London, W1T 2RE, United Kingdom. Fisher Investments Europe Limited’s parent company, Fisher Asset Management, LLC, trading under the name Fisher Investments, is established in the USA and regulated by the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Investment management services are provided by Fisher Investments.

This document constitutes the general views of Fisher Investments UK and Fisher Investments, and should not be regarded as personalised investment or tax advice or as a representation of their performance or that of their clients. No assurances are made that they will continue to hold these views, which may change at any time based on new information, analysis or reconsideration. In addition, no assurances are made regarding the accuracy of any forecast made herein. Not all past forecasts have been, nor future forecasts may be, as accurate as any contained herein.

[i] On a price-level basis. The total-return index, including reinvested dividends, registered a handful of new highs in 2007. But few in media discuss that measure, even though it is a more accurate measure of investors’ experience.

[ii] Source: FactSet, as of 5/12/2017. S&P 500 Total Return Index, 9/10/2007 – 5/12/2017.

[iii] Source: FactSet, as of 22/7/2014. S&P 500 Total Return Index, 16/7/1990 – 24/3/2000.

[iv] Source: FactSet, as of 05/12/2017. FTSE 100 price return, 16/8/2016 – 4/12/2017.