The sanction spiral: Russia and Europe may fall into recession

A trade “tit-for-tat” would hit both sides extremely hard

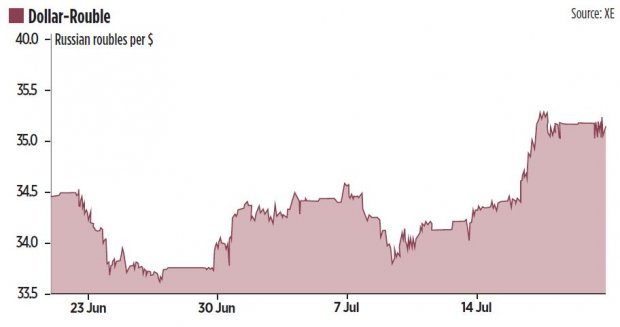

EVEN before the tragic Malaysia Airlines plane crash in Ukraine last Thursday (allegedly the work of Moscow-backed separatists), Russia was already reeling from the US’s tightening of the screws. The country’s Micex stock index tumbled 2.3 per cent to 1,440.63 last week after news that financial sanctions would be stepped up. Deutsche Bank’s respected Russia strategist John-Paul Smith said he expects Russian stocks to be 10 per cent lower by the end of the year – “I don’t think that Russia is a place that non-dedicated investors should really invest in, despite the very low valuations.”

Now, with anti-Kremlin opinion intensifying after Thursday’s plane disaster, and evidence piling up that Moscow may be indirectly linked to the tragedy, the situation looks likely to get even worse for Russia – and the economies of Europe could be dragged in. “I felt last week that markets were too quick to dismiss this,” says Capital Economics chief global economist Julian Jessop. Since then, gold has jumped to almost $1,320 per troy ounce (compared to $1,294 last Tuesday), and Western stock markets have fallen. Fears of a “new Cold War” and a sanctions tit-for-tat between Europe and Russia have spread –“the consequences of all this could be horrible,” says Jessop.

HOW LIKELY IS A SANCTION STEP-UP?

Before the Malaysian jet crash, the consensus was that European leaders would resist stepping up sanctions to target whole sectors of the Russian economy (rather than just Putin’s inner circle). These “tier three” sanctions now seem to be back on the agenda, with Prime Minister David Cameron yesterday saying he had raised the issue with other European leaders. German Chancellor Angela Merkel is likely to be less susceptible to the idea than Cameron, given Germany’s relative proximity to Russia and the interdependence of the two countries’ economies.

But there are several reasons to think the European response could involve measures directly targeting sectors of the Russian economy. First, Europe will not want to seem out of kilter with the US on this issue, argues Ross Denton of law firm Baker & McKenzie. The ongoing negotiations with Iran over its nuclear programme has highlighted the importance of Western unity to many of Europe’s leaders, and they will not want to further break ranks with the US while these talks are live.

Second, Russia would have far more to lose from a sanctions tit-for-tat than the West, says Jessop. Coupled with Putin’s intransigence so far, European leaders could quickly come to the conclusion that much stronger sanctions are the most credible threat to Moscow’s elite.

WHAT MIGHT SANCTIONS LOOK LIKE?

The US has already stepped up financial sanctions, using the dollar’s status as an international currency to hurt key Russian firms. Some commentators, including Eurointelligence president Wolfgang Munchau, have argued that Europe and the UK should pursue similar action against Russia. But according to Denton, this would be difficult. “It would involve acting extra-territorially,” he says.

The US may be prepared to exercise its powers and track down transactions worldwide to enforce sanctions (as the recent fine against BNP Paribas showed), but Europe would be less willing. “Instead, I’d expect them to do more on the trade side,” says Denton. If tier three sanctions are pursued, he says, defence items would likely be the first to go. “And eventually you’d start to see some thought given to oil and gas, given how important these sectors are to Russia.”

WHAT MIGHT THE FALLOUT BE?

Clearly, such measures would hit companies with a significant exposure to Russia hard. Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell and BP have had a difficult month already (see graph). BP lost roughly $4.4bn (£2.58bn) in market value last Thursday, and its relationship with Rosneft (it owns a 19.8 per cent share of the Russian state-owned oil company singled out by US sanctions) could see it dragged down – although Jessop says that a higher oil price could offset part of the pain for the energy firms.

The main casualty is likely to be Russia. The country was already seen as vulnerable to a recession this year, and recent events have only exacerbated the danger. Saxo Bank’s Peter Garnry yesterday said: “It’s almost a certainty Russia is heading into recession this year.” Others have argued that the country’s GDP could shrink by as much as 2 per cent this year. It’s difficult to see how its stock market could recover in such an environment.

And the consequences of a trade sanction tit-for-tat between the EU and Russia would not leave Europe unscathed. “Applying sanctions to Russia is an entirely different matter to Iran or Libya,” says Denton. “Its interests are so interwoven with those of the West.” An obvious issue is over the flow of gas to Europe, and whether Moscow decides to retaliate against energy sanctions and turn off supplies. But the country is also a large export market for many economies in Europe – Italy and Germany have been highlighted as particularly close to Russia.

Jessop says that a trade tit-for-tat would be a “significant headwind for the Eurozone’s recovery”, even tipping it back into recession in the worst case scenario. “It’s difficult to see how this could happen given the hard numbers,” he says. Stocks of natural gas are high, and producers like Norway and others in the Middle East could increase supplies. But combined with an already-fragile recovery, and recent signs of a possible slowdown in Germany (Eurozone manufacturing surveys plummeted to the lowest levels this year in June), it’s dangerous to rule out a further setback to growth. “I wouldn’t underestimate the impact this could have on sentiment – not just in financial markets, but among businesses and even consumers.”