Naked houses: Unfinished homes give buyers a discount price – but are they practical?

In case you hadn’t noticed, Britain is in the grip of its worst housing crisis since the 1940s.

The verdict, delivered in a recent report from the Centre for Policy Studies, will be endorsed by anyone who has endured the vagaries of the London rental market, where a ‘cosy one-bed’ can be a garage with a wastewater problem, and ‘compact studio flat’ can mean ‘the bed folds out of the oven’. And if the rental market can feel cruel and absurd, the prospect of buying property in the capital can seem quixotic, a privilege reserved for the children of aristocrats and arms-dealers.

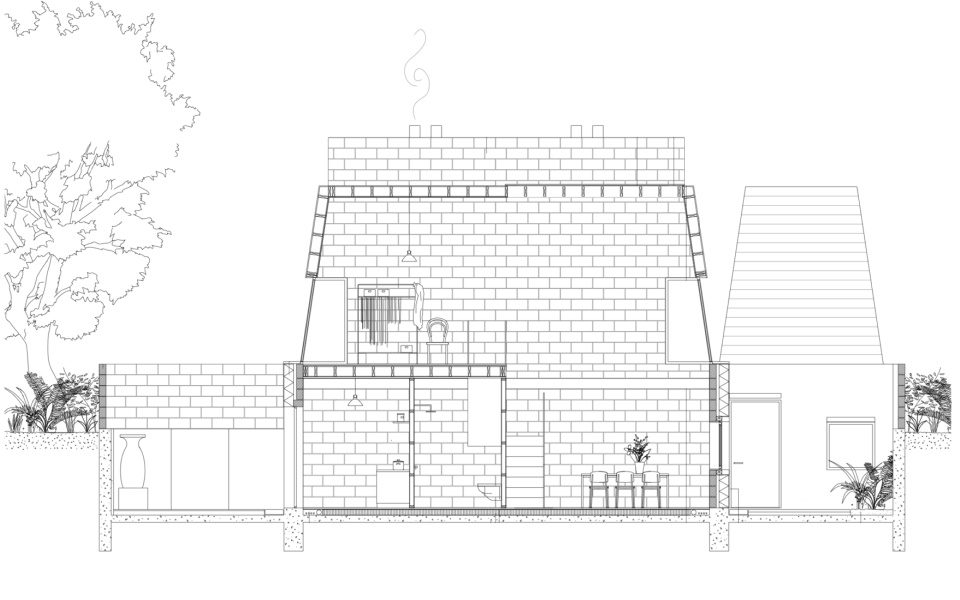

In this dire context, the appeal of property developer Naked House is easily understood. Its pitch is simple: construct sparse, spartan homes stripped of everything but the barest essentials, enabling them to be sold for between £150,000 and £340,000 – an attractive proposition in a city where the average asking price is £618,880.

“Naked” means load-bearing walls but no partition walls; floors but no flooring; a kitchen sink but nowhere to cook. Also removed are any of the accoutrements – rugs, blinds, coffee machines – that jazz up otherwise mundane property brochures, but amplify the price of fully-fitted homes. While Naked House is a non-profit company, it’s found support in exalted places, with the bulk of its funding coming from London Mayor Sadiq Khan.

“The basic idea is to build genuinely affordable homes for working Londoners on moderate incomes,” says Simon Chouffot, one of the company’s founders. “It’s about empowering people to be part of their own solution to the housing crisis. We know around half the population have expressed an interest in custom or self-build but only a fraction do it – a huge unmet demand.” Chouffot has himself felt the sting of the housing crisis: after finding he was unable to afford property in East London, he was driven to living on a boat on the Regent’s Canal.

He’s keen to impress upon me that Naked House has a civic as well as an economic mission, with the building process intended to nourish a sense of common purpose among its inhabitants. “Naked House residents literally build a neighbourhood together,” he says. “This idea of community is so important to many people, especially in a large city like London. Strong communities improve wellbeing, and also reduce reliance on the state through shared childcare and transport costs”.

It’s worth mentioning that there aren’t currently any Naked House residents; while projects are under construction in Lewisham, Croydon, and Enfield, no developments as yet exist.

But Chouffot has cause for optimism. Rival firm Unboxed Homes is currently nearing completion with a similar – albeit more high-end – project, Blenheim Grove in Peckham, which will constitute five terraced ‘shell houses’ selling from £899,995 (two are already under offer) and it has new projects slated for Sydenham and Pound Lane.

When the Dutch studio NL Architects won the 2017 Mies Van Der Rohe prize for its renovation of a dilapidated Amsterdam apartment block, its winning innovation was to allow residents to outfit their own homes. With similar projects already realised in Chile and Manchester, the idea of unfinished housing has begun to solidify into a movement.

So is the end of the housing crisis in sight? Not quite.“Unfinished housing is an interesting concept, but it doesn’t get close to addressing the key issue about the supply of housing, which is the price of land,” says Louise Goodison, director of Cazenove Architects, a firm that focuses on urban regeneration. The real problem, Goodison says, is that progressively more land has been sold to private developers over the past two decades, resulting in the value of London land being driven radically upwards.

There’s also the issue of finishing those unfinished houses, which can be time-consuming, complex and expensive. Housing codes are strict and complex, which means that owners will need to become au fait with London’s often labyrinthine building regulations. They may also find themselves burdened by a host of hidden emotional costs, which Goodison argues are obscured by the “bauble” of an initial mark-down.

Unfinished housing is an interesting concept, but it doesn’t get close to addressing the key issue about the price of land

Louise Goodison, director of Cazenove Architects

“I’ve worked on self-build schemes, and I’ve seen people defeated by it. I’ve seen lives be swallowed up,” says Goodison. “If you’re a certain kind of young person, and have the time and energy to spare, then great. But if you have kids, or work a fifty hour week, will you be able to construct something worth living in?”

Chouffot avoids answering my question about how much it’s likely to cost residents to “finish” their unfinished property, although he argues they are technically habitable from day-one, “in a minimalist sense”. But while a Nespresso machine probably isn’t an immutable feature of the Good Life, many would argue that the privacy afforded by partition walls are.

The housing crisis is not a monolith. For a niche subset of people – young, time-rich, proficient at manual labour – Naked House might provide an answer. But for many others it won’t, and Chouffot’s claim about “empowering people to be part of their own solution to the housing crisis” has the distinct whiff of overreach.

“In some ways I like the idea,” Goodison says. “Self-build projects can be empowering and creative. But this isn’t a solution to anything.”

• For more information go to nakedhouse.org