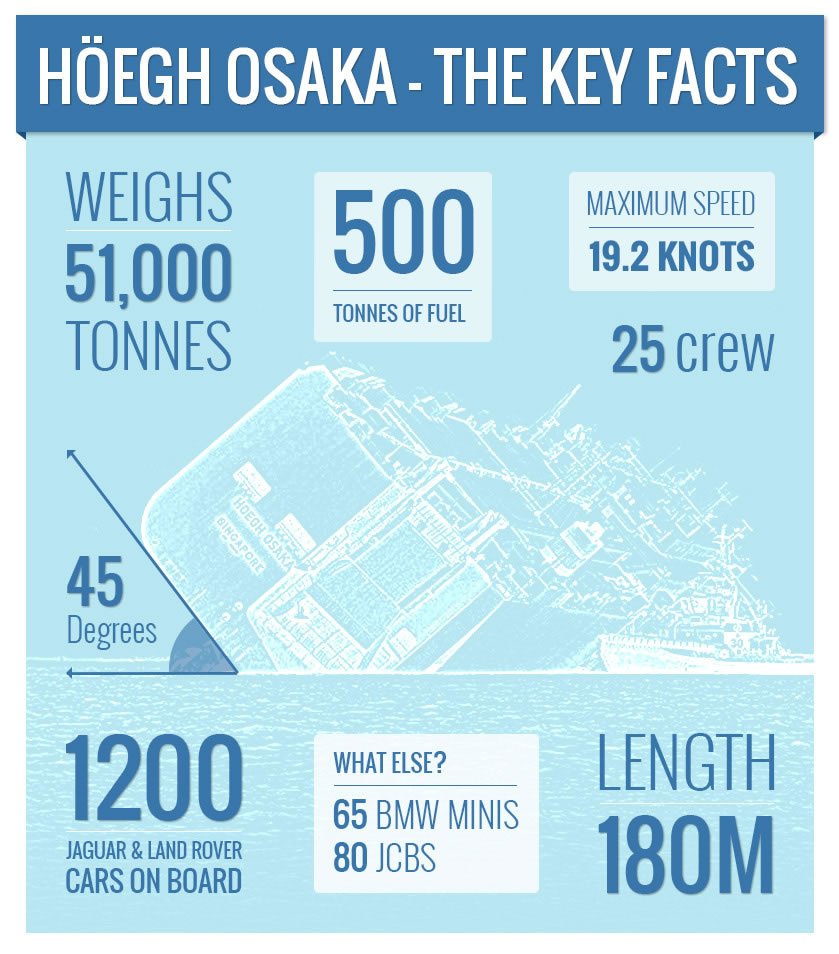

Here’s what could happen to the 1,400 luxury Jaguars, Minis and JCBs aboard the grounded Höegh Osaka

As most people tucked into their roasts on Sunday, the Hampshire Constabulary reported a strange phenomenon: car parks around Calshot, a peninsula down the coast from Southampton, were filling up as tourists flocked to the area to take a look at a stricken car carrier, which had been deliberately run aground.

The 51,000-tonne Höegh Osaka had begun to list dangerously shortly after it left port on Saturday night, and the pilot and master had taken the decision to beach it, in an effort to save its cargo.

“This showed great skill and seamanship on behalf of our crew,” said Ingar Skiaker, chief executive of Höegh Autoliners.

The crew had chosen the Bramble Bank, a narrow area in the channel between the south coast and the Isle of Wight, where at certain times of the year the sands are so exposed by the low spring tide, yacht clubs from the two sides of the channel stage an annual cricket match.

But even once it was grounded, the 590ft vessel was listing at a dangerous 45-degree angle.

The good news is the ship’s 25-strong crew were all safe shortly after. The bad news? Even though it was only at a third of capacity, the Osaka was carrying luxury cars and machinery worth millions, with 1,200 high-end Jaguars and Land Rovers, 65 Minis and as many as 80 JCBs aboard.

Although Jaguar Land Rover told us in a statement that the most important thing “is the safety of the crew”, the FT reckons its portion of the cargo could be worth as much as £60m, assuming those cars, which were en route to be sold in the Middle East, go for £50,000 apiece. So what happens next to the cargo?

Höegh confirmed it has appointed Svitzer, the marine salvage company, whose team has already boarded the vessel. There are high hopes the cargo can be extracted safely, particularly as all the cars will have been tightly strapped down before the ship set sail to avoid damage in rough waters.

But the wrecking of car-carriers isn’t an uncommon event, and although it’s all fully insured, for the cargo, the record doesn’t look optimistic.

In 2006, the MV Cougar Ace, carrying 4,700 Mazda cars, partially capsized in the North Pacific. As work began on the salvage of the vessel (it was eventually rescued, albeit with the loss of one life: a marine architect, whose job it had been to make an on-the-fly 3D model of the ship, fell as he was leaving it), Mazda was faced with questions over what to do with the cars on board.

On the surface, most were perfectly fine: only 68 had been jogged free of their bindings, or damaged by those that had. And although some had been damaged by water, most looked as brand new as the day they were loaded on to the ship. They even had that new-car smell.

Quadcopter footage shows the Osaka listing

But by the time the vessel was righted, the cars had languished for more than three weeks at an angle of 60 degrees, which could, it was decided, make the company liable in the event of any accidents in the future. In particular, the electrolyte in the batteries concerned the company.

“On their sides, it’s not bad. But the saltshaker motion [of the ship at sea] added a lot of damage,” Robert Davis, Mazda North America's then-senior vice-president of product development and quality (now its senior vice president of US operations), told US-based magazine Car and Driver.

So instead of being sold, the Cougar Ace Mazdas – including 2,804 Mazda 3s, which now retail for £16,995 and 295 MX-5s, which start at £18,995 – were painstakingly dismantled, fetching an estimated $250 (£164) apiece at scrap.

One by one, the Mazdas were loaded into an Overbuilt portable crusher and tamped down into five-high stacks about five feet tall with 2400 psi of hydraulic pressure.

A representative of Svitzer has told the BBC that the salvage operation for the Osaka could take “several days”, rather than weeks. But for the cars on board, rescue could be the beginning of the end.