Ed Warner: In defence of the Premier League’s laudable financial rules

The Premier League may be losing the PR battle over their spending rules but they should be applauded for making clubs do the right thing, argues Ed Warner.

Days after Manchester City edge a five-goal thriller, the Premier League’s product is brought back down to earth with a crash. A table already sullied by Everton’s 10-point deduction for breaching financial regulations is now overlaid with added uncertainty through to the end of the season, possibly beyond.

A points penalty for Forest? Another for Everton? And what of Chelsea’s case after its new owners dobbed their club in? And the outstanding 115 charges against City themselves?

The Premier League’s profitability and sustainability rules (PSRs) are biting. Last week Newcastle’s CEO, Darren Eales, made clear they were holding back the ability of his club to capitalise fully on the backing of its new-ish Saudi owners. Wolves have a weakened squad this season, having offloaded players to operate within the league’s restrictions.

You may wonder at many clubs’ predilection for spinning their squads. Eales used a simple example to explain the need to sell players to fund progress, even if the transfer fees for those bought and sold are identical – and the players are of possibly similar quality.

“What’s the point in doing that, you might say? It is risky as we’ve already got that player here and we know what they can do, but if you sell a £50m player and bring in an identical one for £50m, on the same wages, but amortise over the five years the player you are bringing in, that’s only £10m a year. So you are creating £40m of headroom.”

Darren Eales

The key is that transfer costs are spread over the length of a player’s contract in the club’s accounts. Standard accounting treatment for any business asset.

Eales’s example is replete with ifs and buts. It assumes the fee received for the sold player represents a full £50m profit over and above his (depreciated) carrying value on the club’s balance sheet.

Something like this will often pertain for homegrown players, or those bought cheaply when young and developed into Premier League stars. This is one reason why Chelsea have offloaded products of their academy, who have zero or little carrying value on the balance sheet.

The London club have also tied some new recruits to eight-year contracts, reducing the annual amortisation charge against its profit and loss account, so easing their ability to remain within the permitted limit of £105m of adjusted losses over a three-year period. The Premier League has now responded by restricting the period any future contracts can be spread over to five years when assessing compliance with its financial regs.

For some years I chaired a partnership in the financial sector whose approach to remuneration was colloquially termed “sticky up/sticky down”. If successful, you weren’t immediately moved to the profit share commensurate with your contribution. Instead this happened over a few years if you maintained your success. Conversely, if you underperformed you were cushioned for a while to give you the chance to turn things around.

In many ways, the Premier League is operating on a similar principle. New-found wealth can only be fully deployed over time – a process accelerated if new backing helps trigger an upturn in a club’s regular income, from ticket sales and sponsorship.

Parachute payments partially protect those clubs relegated at the end of each season. Taken together, these help level the playing field (jeopardy being a core attraction of the Premier League), encourage some clubs to take more risk, and protect others from the folly of over-extending themselves.

Above all else, PSRs reward those who grow talent rather than buy it in, and who invest in infrastructure that has the potential to generate greater income in the long term. Spending on youth development and the depreciation of tangible assets – think stadia and academy buildings – are excluded from the £105m ceiling on three-year losses. Aren’t those just the priorities you would want your life-long team to have?

The Premier League may be losing the PR battle on PSRs. Its rules and their implementation both certainly need refining. But their underlying intent is laudable. The clue is in the middle initial – sustainability.

Your country needs you

Just when cricketers are turning down contracts with their national teams in favour of the Indian Premier League and rugby stars are choosing (overseas) club over country, the top African and Asian footballers have packed their bags for the Africa Cup of Nations and the Asia Cup at the mid-point of their European club seasons.

Long may this willingness to represent their countries prevail, as this is what wide-eyed kids dream of (even if cynical fathers claim not to care what their national team does so long as their favoured club side prospers).

Africa has only hosted the football World Cup once, in South Africa in 2010. There are many who will say that this isn’t the “real” Africa, such is the politics of the continent. They may take similar issue with Morocco’s upcoming role as one of three joint hosts in 2030. The Olympics have yet to take place on African soil.

Both Fifa and the International Olympic Committee would love the opportunity of a viable solo host from one of Africa’s heartland nations, if only because their leaders are regularly shored up at election congresses by votes from the continent’s delegates. Money – or the lack of it – is clearly the issue, though.

“We find empirical evidence that China employs stadium diplomacy to secure natural resources and to secure diplomatic recognition in line with the One-China policy.”

Hugh Vondracek

Perhaps the two cash-rich owners of the world’s biggest sporting events could engineer soft-power support for African hosts. On a more modest scale precedents exist.

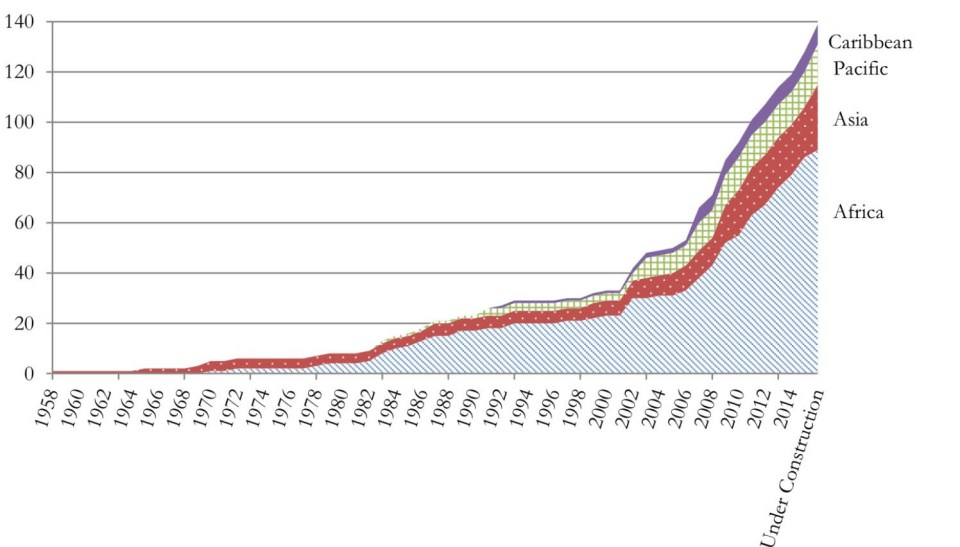

I remember a visit to the Mandela National Stadium in Kampala a few years back. Home for Uganda’s national football team as well as athletics, it was funded by the People’s Republic of China. Just one of 142 examples across 61 countries of Chinese “stadium diplomacy”, an accelerating phenomenon scrutinised by academic Hugh Vondracek in a 2019 study. I was told on my trip that the stadium was an ‘off the shelf’ Chinese design replicated elsewhere in Africa.

You can read Vondracek’s paper here. His graph below shows the cumulative growth of the 142 Chinese-funded stadia by region, as well as the acceleration of the programme. Africa is very much to the fore.

‘I just smell money’

No prizes for guessing those are the words of Barry Hearn. Prompted by this month’s Luke Littler darts mania, a reader who remembered my praise for Hearn’s ability to re-package sports in a recent column sent me a link to a 2022 interview with him on The Darts Show Podcast. Listen here.

“I think any major sportsman that’s sacrificed and really paid his dues, could be a really good business person, if they take the same rules of life and extend that to business, because there’s no short cuts.”

Barry Hearn

A compelling hour. The pod roams across darts, snooker and boxing. Pinches of salt might be needed for some of the promoter’s claims, although his suggestion that viewing figures on Sky for a routine darts competition are four times those for the equivalent golf tournament is quite the showstopper – and would give heart to many secondary and tertiary sports if only they could find their equivalent business alchemist.

Ed Warner is chair of GB Wheelchair Rugby and writes his sport column at sportinc.substack.com