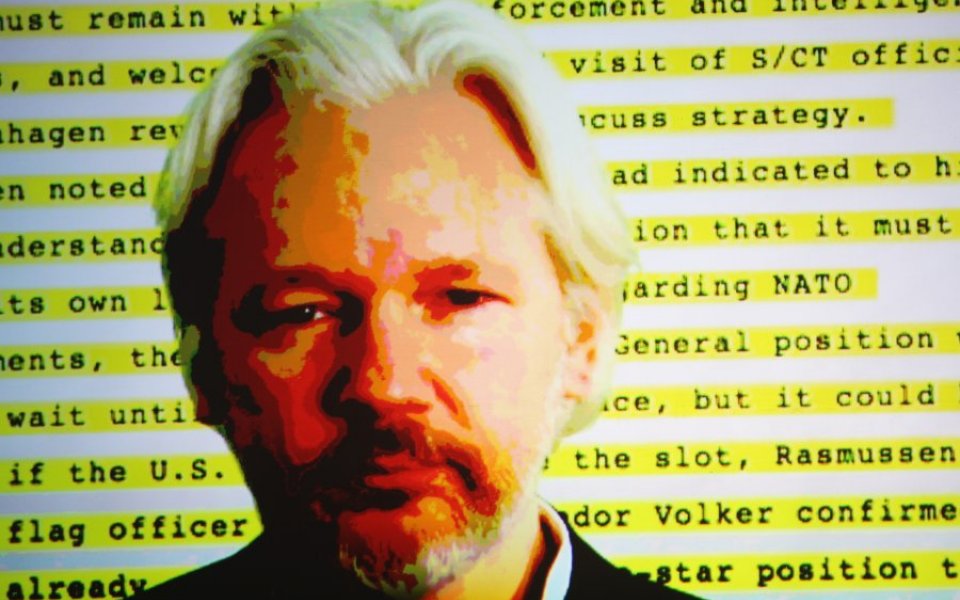

Why Julian Assange shows that only intelligent machines can be truly rational

Is Julian Assange rational? There are no prizes for guessing the responses of most City A.M. readers to this question. He faces questioning over allegations (which he denies) in Sweden, and he claims that America will try to extradite him and put him in prison for a very long time. Assange has chosen instead to live within the confines of the Ecuadorian embassy in London for over three years.

On one level, economic theory can easily account for his behaviour. As a rational decision-maker, he estimated the potential costs and benefits of alternative courses of action, compared them to his preferences, and made what for him was the best possible decision. He probably considers the embassy to be preferable to life in a maximum security US jail. All standard economics textbook stuff: the costs of leaving the embassy outweigh the benefits.

But in forming his views on the costs and benefits, Assange had to make some quite difficult assessments of the likelihood of future events. What are the chances of him being charged by the Swedes? What is the probability of the Americans both trying and succeeding in getting him extradited? What is the likelihood of being found guilty if he is ever bundled over to the US? The answers are not obvious and there is no easy solution.

Even his ploy of getting the ludicrous United Nations panel to pronounce that he has been “arbitrarily detained” shows the inherent uncertainty around future events. Assange could have been almost certain that it would find in his favour. But it would have been hard for him to anticipate the ridicule with which this has been received, even among the liberal left. Making choices which involve future consequences is a much more difficult problem than simple economic choice theory might lead us to believe.

Assange could perhaps have benefited from the remarkable algorithm developed by a team at Google DeepMind, and described in a paper in the top scientific journal Nature last month. Their work seems to be a very important step towards creating intelligent machines. The programme defeated the European Go champion 5-0. “So what?” you might say. But Go is an immensely harder problem than chess to attack by purely straightforward computational power. Success depends much more on a deep intuition of what does or does not constitute a good position. The astonishing feature of the algorithm is that it makes moves, in positions which have occurred previously in human games, which even the strongest human players simply cannot understand.

The implications spread far beyond the game of Go. The algorithm faced a challenging decision-making task. The precise consequences of a move cannot be computed. The optimal solution is so complex that it is infeasible to approximate. Yet the algorithm succeeded. Maybe humans have created the first truly rational thinker.