The UK economy has defied gloomy expectations. Can this continue?

The UK economy has surprised pundits again and again this year, growing at a much faster rate than almost anyone had expected.

In the first quarter, the economy grew 0.7 per cent, making it the fastest growing economy in the G7. After May’s GDP figures, which showed a 0.4 per cent expansion month-on-month, many economists think this could be repeated in the second quarter.

A raft of forecasters, both in the City and beyond, have been bumping up forecasts for the UK, with consensus for annual growth now approaching one per cent. At the start of the year it was nearer 0.5 per cent.

So why has the economy performed so much better than expected?

Sanjay Raja, chief UK economist at Deutsche Bank, said last year’s shallow recession might actually be contributing to stronger growth this year, reflecting what economists call ‘catch-up’ effects.

Last year the economy grew just 0.1 per cent, well short of its potential growth rate. This means there was unfilled capacity in the economy which is now, unsurprisingly, being utilised.

The fact that the UK is growing more strongly than expected suggests that economists had underestimated the UK’s output gap, how far output is from its potential output. This meant the ‘catch up’ effects this year were stronger than anticipated.

The backdrop for consumers has become significantly more supportive over the past few months too. With inflation back at two per cent and wage growth still strong, households are receiving a significant boost in disposable income.

Disposable income rose by 0.7 per cent in the first quarter, which helped consumer spending to rise by 0.4 per cent in the same period.

Ashley Webb, UK economist at Capital Economics, expected this supportive backdrop to continue. The consultancy expects real household income to climb by 2.5 per cent across 2024 and between 3.0 and 3.5 per cent next year.

While consumers have played their part in fuelling economic growth, there could be more to come. Households are spending more than they were during the cost-of-living crisis, but they are not spending anywhere near as much as they were in the 2010s.

Data released this week by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) showed that the savings ratio climbed to just over 11 per cent in the first quarter of this year. During the 2010s the savings ratio averaged 6.3 per cent.

The savings ratio measures the amount of disposable income which consumers squirrel away rather than spend. The significant increase in savings since the pandemic is likely a reflection of the many different shocks households have faced over the past few years.

Higher interest rates will have also made it more attractive to save.

The ONS noted that consumers in the US have been much more willing to spend, which has been “an important factor in supporting household consumption and economic growth”. The spike in savings suggests there is further scope for consumption to increase if sentiment improves.

It also means that household savings exceed debt for the first time on record. “UK household balance sheets haven’t looked this strong for quite some time,” Raja said.

With inflation more or less back under control, the Bank of England is likely to start cutting interest rates in the next couple of months, which should provide a further tailwind to growth.

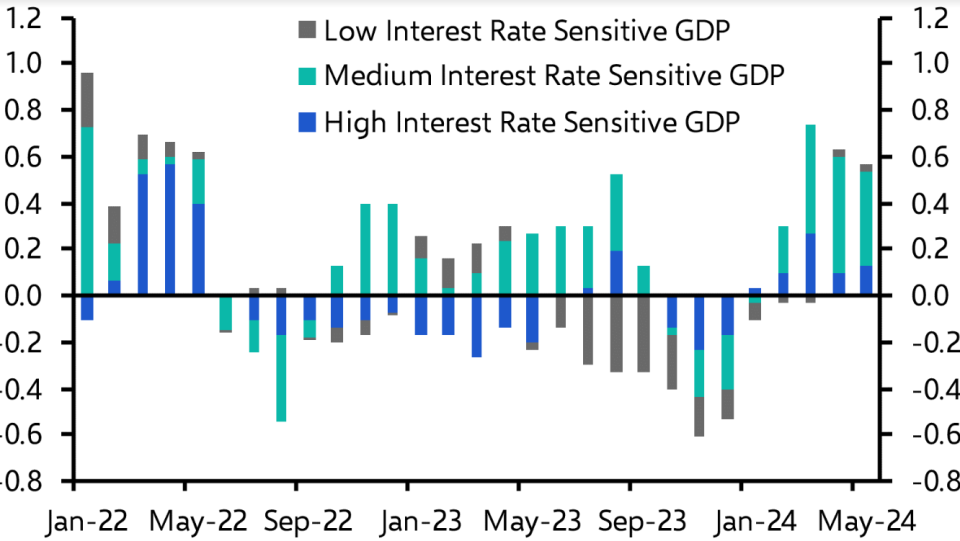

Indeed, the prospect of lower rate cuts already has. Analysis by Capital Economics suggests that the sectors more sensitive to interest rates have contributed the most to GDP growth. This includes construction, retail and hospitality.

There’s still plenty of work to do. Potential growth has fallen dramatically over the past 20 years while living standards have barely increased since 2017, so Labour’s “national mission” to make the UK the fastest growing major economy in the world is welcome.

But the foundations are likely a little stronger than most observers thought at the beginning of the year.