The British energy giant set to light up America

National Grid boss Steve Holliday has ambitious US plans, he tells Roger Baird

It is entirely appropriate that Steve Holliday, the 51-year-old chief executive of National Grid – which runs Britain’s power network – is a bundle of energy.

The engaging, former fly-half club rugby player gesticulates constantly and frequently bounds across his large London office overlooking Trafalgar Square to grab a chart, better to illustrate points about the £17bn-rated giant business he runs.

But to be fair, Holliday has plenty to get excited about. For a start, last week New York regulators approved £750m of electricity upgrades for his US business.

Upgrading its American and British networks is the basis of the firm’s business model. Approved upgrades by its regulators means it can charge power generators more to distribute their energy along its network.

As Holliday says: “Investment leads to returns.”

National Grid has committed itself to spend £16bn between now and 2012 in Britain and America as it not only upgrades an aging network that dates back to the 1920s but also prepares the system to handle an expansion of green and nuclear energy.

This also puts Holliday, who has led the 28,000-strong group for two years, at the heart of national debates on both sides of the Atlantic concerning security of supply, climate change and soaring energy costs.

Reputation for shrewd deals

Since Holliday has taken over he has gained a reputation in the City for disposing of assets at top prices. He sold the group’s network of mobile phone masts to Macquarie for £2.5bn, a move in which the group doubled its money in less than two years.

In the meantime, the £4.2bn acquisition of US energy group Keyspan, a deal that had been agreed by the previous management, finally won regulatory approval.

But investors are worried about growth in the complex US market, where National Grid reports to four state bodies along the Eastern seaboard and to the federal energy regulator.

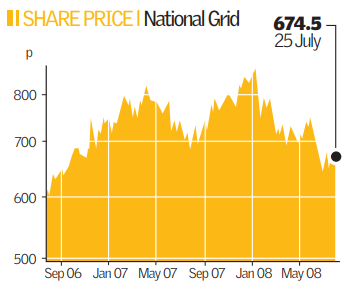

Evo Securities analyst Lakis Athanasiou said: “What the market is really unsure about is visibility in the US market. Part of the reason the share price has fallen recently is because investors are unsure if National Grid will be able to implement their plans there with so many bodies to report to.”

But Holliday points to the New York electricity deal as evidence that the group is able to make progress on its investment plans.

He said: “The US system is complex. But if you can master it, it presents opportunities. And we have a lot of very clever people in the firm who can work on issues like these.”

In the UK, where National Grid will carry out much of its spending over the next four year, Holliday to all intents and purposes expects to be the sole network provider.

The Department of Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR), which handles energy policy, had made noises earlier this summer about letting another provider connect a series of proposed Scottish wind farms to the national network. But National Grid believes it has headed this argument off on cost grounds.

Holliday said: “The scale of our business provides economies of scale and allows us to standardise procedures at a high level. Those are powerful arguments that government and the regulator are listening to.”

Rising debt threat

National Grid is Britain’s biggest issuer of corporate debt after the banks, with around £15bn of outstanding loans. While rising debt costs remain a threat due to the impact of the credit crunch, Holliday does not seem excessively worried.

He said that when the firm closed a £595m bond, priced at 0.8 per cent above Libor, the inter-bank lending rate, in May, he found that there were high lending rates in the market. But when he went to back to his banks a few weeks ago to borrow around £300m, he found these rates had eased.

Holliday said: “In our case, 95 per cent of our cash flow is locked in because of the nature of our regulated businesses. We are a strong business to lend against, and there is an appetite for our debt.”

National Grid is also planning for the building of a new fleet of nuclear reactors, after the government said this will cut carbon emission and ensure a secure energy supply in Britain.

Holliday said the first plants will not be built until 2017 at the earliest, but because they will be twice as big as their predecessors, they will also require upgrades twice as big to connect them to the network.

He said: “We are beginning to think hard about where those plants might be, and what kind of investment from us they will require.” Observers say nuclear upgrades will cost National Grid an extra £3bn-£4bn.

Holliday said the business usually thinks seven years ahead. But with the addition of key questions around security and supply and nuclear investment, its time frame has been pushed out to 20 to 30 years. And that is enough to keep any chief executive on his toes.