Starmer’s EU deal risks stifling the UK’s thriving gene editing sector

Aligning with EU on genetically modified food and agricultural products will create a regulatory cliffedge for a sector which has investors queuing and in which Britain has the chance to lead the world, says Matthew Bowles

Last week, Sir Keir Starmer unveiled plans that could risk quietly derailing one of Britain’s fastest-growing scientific sectors, all in the name of “alignment”. Starmer announced controversial plans to reopen the post-Brexit EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, raising many eyebrows. Among the proposals discussed during the Summit were extending European trawlers’ access to UK waters until 2038 and an agreement for the United Kingdom to dynamically align its agri-food standards with the EU.

Much of the commentary has since focused on fishing rights and food trade. But buried beneath these headline-grabbers is a deeply concerning – and largely ignored – detail, the reintroduction of the EU’s Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) regime, a strict set of rules governing food and agricultural products that could heavily restrict gene editing applications. Whilst it may sound like dry trade policy, for the UK’s flourishing gene editing sector, it’s a regulatory iceberg.

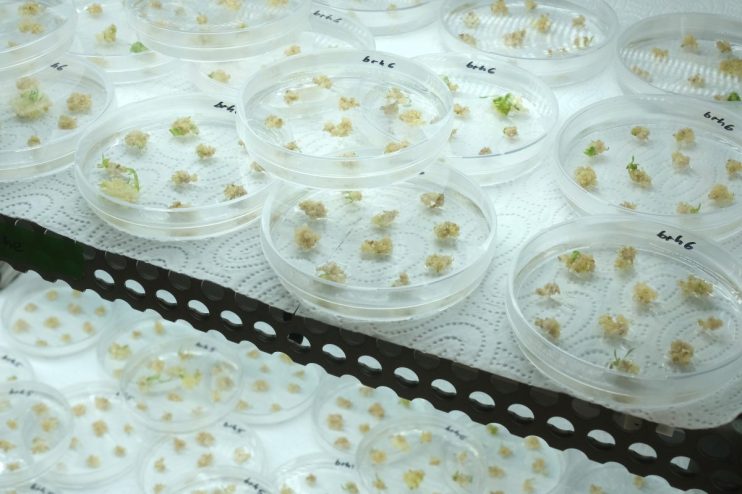

Picture a biotech lab in Cambridge. White coats, centrifuges humming, and a team of scientists celebrating a breakthrough in gene editing that promises to revolutionise crop yields or eliminate a rare disease. A queue of investors are lined up, start-ups are scaling, and Britain, finally free of the EU’s scientific red tape, is leading the world in this cutting-edge field.

Then suddenly, this is no longer possible. Under the guise of regulatory “cooperation,” realignment with EU rules would re-impose the very framework that drove our brightest innovators overseas in the noughties. This isn’t just hypothetical; it’s a political decision unfolding in real time.

In the early 2000s, Europe became a hostile environment for biotech innovation, particularly relating to gene editing and genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Driven by the innovation-harming precautionary principle and mounting public suspicion of “Frankenfoods”, the EU adopted an increasingly rigid regulatory framework. This culminated in an effective moratorium on new GMO approvals and a labyrinth of red tape that made even experimental trials an ordeal. This signalled an existential threat for UK-based biotech firms, many of which were at the forefront of agricultural and medical gene technologies.

The result? An exodus. Ambitious startups and research outfits packed their bags for more scientifically literate jurisdictions. Countries such as Canada and the United States provided an alternative science-led, transparent approval process.

Thorben Looje, Director of Valto, moved operations from the Netherlands to Canada, citing more straightforward regulations and a greater space for product development. Syngenta, the last company with significant GM crop research capability in the UK, expanded its research and development in North Carolina, USA, investing a total of $72m in a new advanced crop laboratory in 2013. This move was part of a broader strategy intended to focus on markets with more supportive regulatory environments. This is an issue for all EU countries, not just the UK.

Brexit was a fresh start

Brexit, however, offered the opportunity of a fresh start, with a regulatory framework tailored for innovation. But with the latest murmurings of dynamic alignment under the Starmer government, history risks repeating itself.

In recent years, the UK’s gene editing sector has rapidly emerged as a world leader, attracting both global attention and investment. According to the Cell and Gene Therapy annual review, the financial year ending March 2024, the sector drew in nearly a billion in funding, a notably impressive vote of confidence in British scientific innovation. This may sound like quite a small figure, however when compared to our European counterparts, UK companies secured 55 per cent of Europe’s cell and gene therapy VC funding in 2023, putting us only behind the United States and China in overall life sciences investment.

This surge in investment is not merely financial; it reflects the UK’s unique ability to blend academic excellence with commercial application in biotechnology. For example, T-Therapeutics, a Cambridge-based biotech company focused on developing next-generation T cell receptor (TCR) therapies for cancer and autoimmune diseases, raised £48m through a Series A financing round.

Equally striking is the UK’s regulatory agility post-Brexit. In a landmark move, British authorities approved Casgevy, a CRISPR-based gene therapy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, in 2023. This made the UK the first country in the world to greenlight a CRISPR treatment for clinical use, which underscores not only scientific leadership but also our potential to deliver life-changing therapies to patients faster than other nations. Gene editing technologies (like CRISPR) have been regulated under the strict framework as GMOS by the EU, following a 2018 European Court of Justice ruling.

A one-size-fits-all regulatory framework

Re-aligning with the EU’s SPS measures may very well resurrect the regulatory barriers that stifled the UK’s life sciences and biotech sector in the 2000s. Professor David Collins of City Law School has been vocal about the potential fallout. Collins warns that realignment with the EU could severely restrict the UK’s regulatory autonomy, particularly in areas like gene editing and precision breeding. Such a move may not only hinder domestic innovation, Collins argues, but also jeopardise burgeoning trade relationships with key partners like Canada and Australia… countries that have adopted more science-based, permissive approaches to biotechnology regulation. In other words, re-adopting EU rules could alienate allies and partners, and the echoing of previous setbacks: innovation fleeing to more welcoming jurisdictions.

Ultimately, the UK stands at a crossroads. On one path lies a forward-looking regulatory framework that champions innovation, nurtures our gene editing sector, and cements Britain’s position as a global leader in biotech. On the other is a retreat into the stifling embrace of EU SPS measures, rules that have already contributed to an exodus of pioneering companies and investment.

Post-Brexit Britain has a chance – albeit a small one – to become a country where nimble regulation enables the economy to flourish. Despite there not being many sectors where this is evidenced, the UK’s gene editing industry comes closer than most. With a billion invested in the sector, and approval of groundbreaking CRISPR therapies like Casgevy, the momentum is real. But it is also fragile.

Re-aligning with Brussels on SPS risks imposing a one-size-fits-all regulatory framework that could limit this growth just as it begins to gather pace. As Professor David Collins warns, such a move could also sour relations with allies and trading partners like Canada and Australia, whose more permissive approaches have positioned them as biotech hubs in their own right.

If this government, like its predecessors, believes in “science superpower” rhetoric, now is the time to prove it — not by shadowing Brussels but by backing British ambitions with regulatory courage.

Matthew Bowles is strategic partnerships manager at the Institute of Economic Affairs