Record number of Brits return to workforce but inflation continues to wipe out pay growth

A record number of Brits are returning to the workforce in a sign that labour shortages that have held back economic growth and pushed up inflation are starting to unwind, official figures out today show.

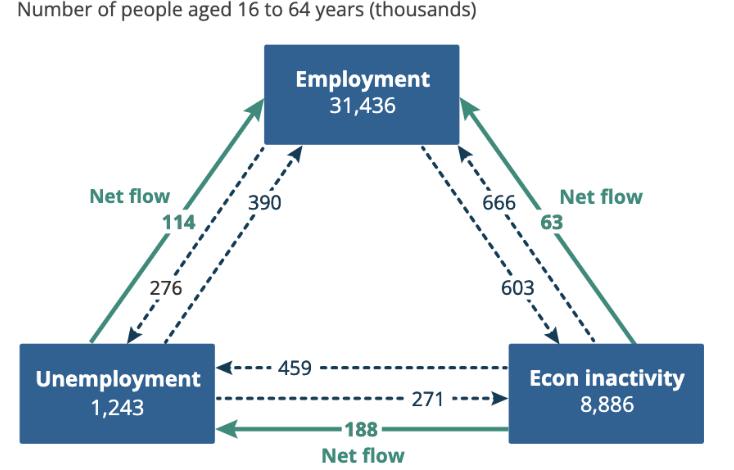

A net 251,000 people flowed out of economic inactivity in the three months to March compared to the previous quarter, the highest total the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has recorded since it started monitoring the data.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, Britain has been grappling with an unusual increase in people dropping out of the jobs market altogether. Other countries in the G7 have registered increases in worker participation.

Economic inactivity – which refers to people out of the job and not looking for one – has jumped since the start of the virus and the ONS said today the rate was up 0.8 percentage points over the same period.

Experts have identified several reasons for the spike in idleness, including long-term sickness possibly related to patients being unable to receive routine care as a result of the enormous NHS backlog.

A net 251,000 people left economic inactivity last quarter

The ONS said the volume of people within the economic inactivity cohort due to persistent sickness climbed to a record high last quarter of just over 2.5m.

There has also been a jump in older workers taking early retirement and a rise in the student population, each of which have raised economic inactivity rates.

An increase of 95,000 students taking up a job or are looking for one over the last quarter was the main factor driving economic inacrtivity lower. An additional 86,000 Brits left the jobs market as a result of being too sick. Some 23,000 came out of retirement and back into the workforce, according to ONS numbers.

“The recent drop in inactivity has been driven by students looking for part-time work and a full reversal of the rise in early retirement seen during the pandemic, both likely due to cost of living pressures,” Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said.

Within the ONS’s figures, there are signs companies are responding to the UK’s economic slow down by trimming staff to shore up their finances.

“The number of people on employers’ payrolls fell in April for the first time in over two years,” Darren Morgan, director of economic statistics at the ONS, said.

Over the last month, payrolled workers – which is tracked using more up-to-date HMRC numbers – fell 136,000, the first drop since the middle of the pandemic and huge increase from the City’s expectations of a 25,000 increase.

Vacancies decreased for the tenth quarter in a row, down 55,000, pushing the ratio of unemployed people per job opening up to 1.2.

Britain’s unemployment rate nudged higher to 3.9 per cent, although that is still historically low. It was mainly pushed up as a result of the influx of people back into the jobs market.

Workers’ living standards continue to be crimped by inflation, which has raged all year and is still running high at 10.1 per cent.

Real wages when accounting for the consumer price index, Britain’s official inflation measure, fell 4.8 per cent, among the largest falls since records began in 2001.

Most of the ONS’s measures of pay growth cooled over the last three months, sparking a number of calls from economists that evidence is building that will convince the Bank of England to pause raising interest rates at its next meeting in June.

“The labour market loosened by a bit more than the Bank of England expected in March. That may alleviate some pressure on the Bank to raise rates,” Ashley Webb, an economist at consultancy Capital Economics, said.

Others said there’s still a risk that last year’s price surge could have shifted firms and households’ behaviours in such a way that could fuel inflation, keeping pressure on Governor Andrew Bailey and co.

“The continued embeddedness of high inflation expectations in the labour market threatens to generate further inflationary persistence, posing a dilemma for the Monetary Policy Committee,” Paula Bejarano Carbo, associate economist at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, said.