Inside London’s occult bookshops

As I stood outside Watkins Books, the oldest occult bookshop in London, an old man approached me. “Number 23 is the one you want,” he said, pointing down the street. I looked confused. “Murder! A woman stabbed in the basement!”

The man, who quickly walked on, was referring to the 1961 murder of Elsie Batten, a 59-year old assistant who worked in an antiques shop. The crime had nothing to do with Watkins, based at 19-21 Cecil Court, but the brief interaction gave me the sense that it was a mysterious place.

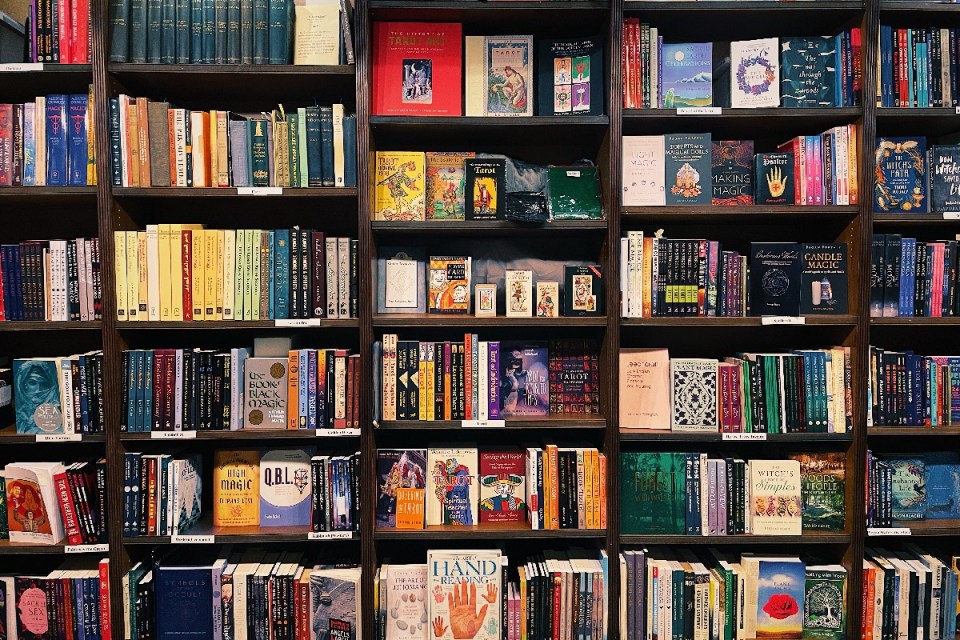

Inside you can find books on folklore and self-help alongside healing crystals, tarot cards and ‘sacred’ sculptures. Downstairs are the books on magic, mysticism and tantric Christianity. It’s an eclectic mix.

Carl Nordblom, the scholarly store manager of Watkins, says the shop embodies “a willingness to explore and seek to have direct experiences – not just theories – of that which all religions talk about, something more than human.” Gulp.

London’s occult bookshops might go unseen by most passers by, but they have seen a lot. Watkins was established in 1893 near Charing Cross, the historic centre of London, moving to Cecil Court in 1901. Atlantis Bookshop, the other mainstay in the city’s occult scene, was founded in 1922, and has been based on Museum Street since 1941.

The two shops are among the oldest bookshops in London. They had a duopoly on the world of occult books until 2003, when Dr Christina Oakley-Harrington established Treadwell’s, which is now based in Bloomsbury. The three are within a 25 minute walk of each other, so visitors to London interested in the occult often visit all three.

But what actually is the occult? “The word means ‘hidden’,” says Geraldine Beskin, co-owner of Atlantis and a self-described practising witch.

”You can plan a party, pick the perfect day and make sure everything is as it should be, but that doesn’t mean the party will be perfect. The occult is that indefinable something. You can’t grasp hold of it, but you can see it working.”

The items stocked in the occult shops claim to help customers to engage with this inexpressible force in a variety of ways, whether through greater self-awareness or elaborate magical practices. Alongside these, there are more familiar volumes on history, philosophy, and nature.

At Atlantis we field questions about witchcraft, from the very basic to very specialist, in a practical way. I’ve been working in the shop for over 50 years so we can hopefully steer people in the right direction

Each shop has its own speciality: “We are like pubs. We each have our different character,” says Beskin. Atlantis has a special connection to modern witchcraft, or Wicca, a religion founded in the mid-20th century by Gerald Gardner. In 1952, Gardner held his first coven in the Atlantis basement, which Beskin says is “arguably the most magical room in London”. That fact alone makes the shop the birthplace of Wicca, the only modern religion Britain has ever produced.

“At Atlantis we field questions about witchcraft, from the very basic to very specialist, in a practical way. I’ve been working in the shop for over 50 years so we can hopefully steer people in the right direction in a gentle way,” she says.

Watkins is more international in its aspirations. The shop was established when theosophy – a religious movement that sought theological insight through mystical intuition – was sweeping the drawing rooms of late Victorian London.

“Theosophists held the belief that at the centre of all religion, was a unified core. You could study all kinds of religiosity and you could find an essence,” says Nordblom.

This helps explain the dazzling variety of books on offer in the shop. Nordblom says international visitors find books they can’t source elsewhere.

Watkins also embraces some of the stranger parts of the occult, with shelves for subjects including ‘paranormal’ and ‘secret societies’.

Treadwell’s, the relative newcomer, avoids the most whacky topics. “Our speciality is that we overlap with the academic world,” says Oakley-Harrington.There’s no self-help, no UFOs and no alternative healing. Part of the purpose of the shop was to help bridge the divide between occult practitioners, who were suspicious of scholars working in the same field, and the scholars, who did not want to be labelled as “weirdos” in the academy, she says.

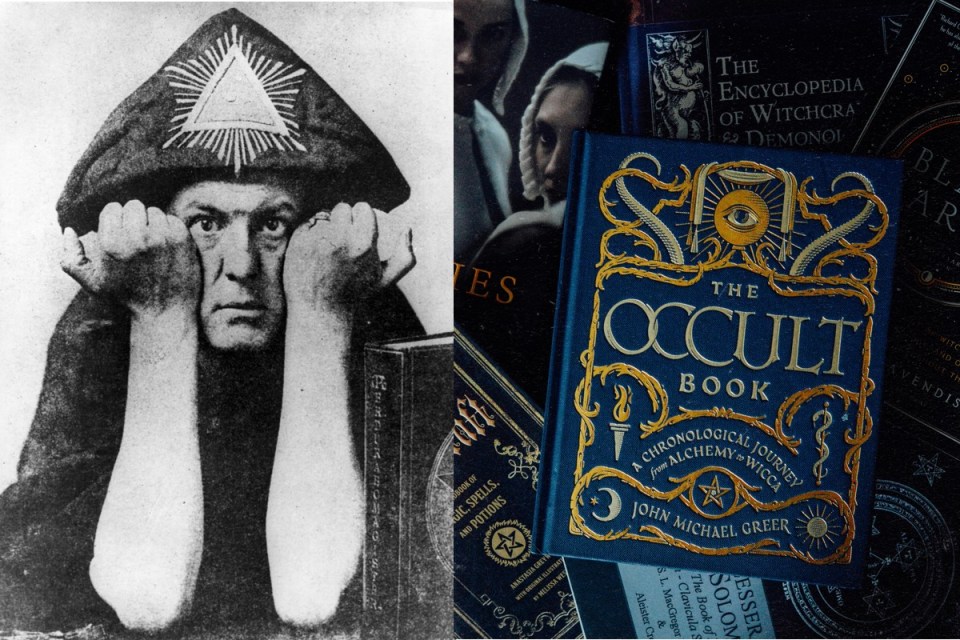

London has had a rich occult history, stretching back to the Roman Age. In the second and third centuries, traders, soldiers and administrators would gather in the underground temple devoted to the Persian god Mithras for secret rites and rituals.

For the next thousand years, some of the most influential Londoners have been deeply immersed in occult practices. In the 16th century, John Dee was an important advisor to Elizabeth I, a founding fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and an occultist. Quite the CV.

Similarly, Isaac Newton spent years of his life studying occult messages in scripture. “Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians,” John Maynard Keynes, the great 20th century economist said of him.

The sacredness of nature is often embedded at the root of occult thought, making it well-suited to modern environmental movements

Although modern science gradually parted ways with the occult in later centuries, it has remained an important influence on religious and cultural life in the city. In the swinging sixties, Mick Jagger was known to go into Watkins Books while Jimmy Page, guitarist of Led Zeppelin, established his own short-lived occult bookshop in Kensington in the early 1970s.

Even in the most modern and most rational parts of the city, the occult still makes its presence felt in unexpected ways. When Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England, published his book dissecting the causes of the global financial crisis, he called it ‘The End of Alchemy’, referring to the ability of banks to simply create money out of nothing. “For centuries, alchemy has been the basis of our system of money and banking,” he wrote. Dee and Newton’s dream was realised at last, not through divine aid but through the wizardry of fractional reserve banking.

So are we living through an occult revival? “There always seems to be an occult revival,” says Nordblom. And in some ways this is true. The occult is such a broad church that some element of popular culture will likely touch on it, consciously or not. Oakley-Harrington says this gives each wave of revival a distinctive character. “This occult revival is different to the Harry Potter revival, or the Buffy the Vampire Slayer revival.”

One distinctive aspect this time around is the importance Gen Z places on that great modern buzzword: authenticity.

“Self-expression and authenticity are very important to young people,” she says. “They don’t want to be in corporate lock-step, so they look to the occult practices of outsiders through the ages, particularly women, for expressions of personal creativity.” Tarot cards and witchcraft are two of the practices enjoying a resurgence.

The lockdowns also generated a wave of enthusiasm for folklore and nature, she says. “We had people of all ages coming in to look for books about how to connect with the land, how to spot trees, and walking routes to megaliths and stone circles.”

While it might seem that spiritual practices adorned with millennia-old symbols might not be the most natural fit for the modern world, many occult beliefs align better with mainstream thought than the major religions. The sacredness of nature is often embedded at the root of occult thought, making it well-suited to modern environmental movements. “Witchcraft is a nature religion,” stresses Beskin.

Witchcraft and feminism also sit comfortably together. After all, the witch is one of the few symbols of independent female power in the Western tradition. And if you are wondering whether a man can be a witch, the answer is yes: “Men make fabulous witches,” says Beskin.

Ronald Hutton, a leading historian of paganism, said there is a “splendid paradox” with modern witchcraft and paganism more broadly. Although witchcraft was first presented as the planet’s “most ancient religious tradition”, its emphasis on feminism, environmentalism and enlightened self-realisation means it is “especially well-suited to radical late modernity.”

Such theorising is all well and good – but it was time to put the occult to the test. Approaching my first tarot reading at Watkins Books, there were precisely two thoughts in my head: “I don’t really believe in this” and “Maybe I am the chosen one”.

“This is a very beautiful set,” says Wendy. “It is benevolent, hopeful, even wonderful. So golden and beautiful. There’s no poverty or destruction, and lots of creativity.

As I arrive, I’m shown to a gloomy corner where Wendy Erlick, my tarot reader, sits in a small alcove. “Welcome to the table,” she says dramatically. I draw the green curtain, pull out my notebook and she begins to turn the cards.

At the centre of my table lie two cards: the four of wands is “blessed and auspicious”, symbolising harmony and celebration. The second card is the three of pentacles, Wendy’s favourite. It’s a card of service and community. “I like working with people who draw this card,” she says.

A succession of other cards follow, showing twists of colour, ghostly figures and an intrepid boat. Apart from a deep, unresolved sadness, things were looking good. “This is a very beautiful set,” says Wendy. “It is benevolent, hopeful, even wonderful. So golden and beautiful. There’s no poverty or destruction, and lots of creativity. But we’ll have to talk about that,” she says, pointing to a sombre looking card adorned with what looks like a pale blue teardrop.

The cards were drawn before I had told Wendy anything about myself. I then explain I am a writer, pursuing the dream of being a freelance journalist, but the climate for freelancer journalists is precarious and I might have to put my dreams on hold. “You will break through,” she says firmly.

I do not tell Wendy that I also harbour musical ambitions, but she knows anyway. She suggests I might have to wait until I turn 28, but that it will be worth the wait. “One day you will write a song that everyone will sing. You can write that down,” she says, gesturing at my notebook. I like tarot readings, I thought.

And what about that unresolved sadness? Well, that’s between me and Wendy. I drew the curtain for a reason.