Geopolitical shock: regime change in inflation and monetary policy

Globalisation is besieged on multiple fronts. Two years after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and amid growing geopolitical unrest, the decades-long disinflationary headwind has reversed.

Many multinationals have taken steps to address the disruptions to their ultimately brittle global value chains. These companies are re-orienting to prioritise availability over cost-optimisation.

This process manifests in three ways: regionalisation (moving supply chains closer to key markets); nearshoring (shifting supply chains to neighbouring centres of production); and reshoring (reversing, in part, the cost-saving offshoring of previous decades).

Inflation is one key consequence. Reorganising far-flung global manufacturing hubs into redundant regional supply chains demands increased capital investment and resource expenditures on everything from logistics to management. Such improvements cost money, and consumers will ultimately pay higher prices in return for more reliable supply chains.

‘Peace dividend’ could erode further

Globalisation and the increasingly efficient resource allocation of recent decades hinge on the geopolitical stability of the post–Cold War era.

The Soviet Union’s collapse and China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) enabled cost-convergence between once-segmented commodity and labour markets. This created disinflationary pressure in the advanced economies.

In retrospect, the Iron Curtain was a significant barrier that kept bountiful grain harvests and energy resources from developed economies.

Nevertheless, as cracks develop along geopolitical fault lines, new obstacles could emerge to disrupt global trade. The ‘peace dividend’ of the past 30 years could erode further: blockades, embargos and conflict could create costly supply-chain detours.

Inflation ‘paradigm shift’ constrains monetary policy

Against the backdrop of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and prolonged pandemic-related disruptions, Agustín Carstens of the Switzerland-headquartered Bank for International Settlements (BIS) acknowledged last month that ‘structural factors that have kept inflation low in recent decades may wane as globalisation retreats’.

“Looking even further ahead, some of the structural disinflationary winds that have blown so intensely in recent decades may also be waning,” BIS’s general manager warned in a speech.

“In particular, there are signs that globalisation may be retreating,” Carstens told the International Centre for Monetary and Banking Studies. “The pandemic, as well as changes in the geopolitical landscape, have already started to make firms rethink the risks involved in sprawling global value chains. And, regardless, the boost to global aggregate supply from the entry of some 1.6 billion workers from the former Soviet bloc, China and other EMEs [emerging market economies] into the effective global labour force may not be repeated on such a significant scale for a long time to come. Should the retreat from globalisation gather pace, it could help restore some of the pricing power firms and workers lost over recent decades.”

Under Carstens’ framework, a paradigm shift on inflation is also a paradigm shift on monetary policy.

The major central banks have had significant operational freedom to engage in unconventional monetary easing — money printing — thanks to globalisation’s disinflationary effects. Renewed inflationary pressure could shift this dynamic into reverse. Rather than apply quantitative easing (QE) in response to virtually all downside shocks, central bankers would need to calibrate future support to avoid exacerbating price pressure.

How the ECB and Fed have responded

Despite these changing circumstances, both the European Central Bank (ECB) and US Federal Reserve maintained interest-rate suppression policies well into the supply-led inflation spike.

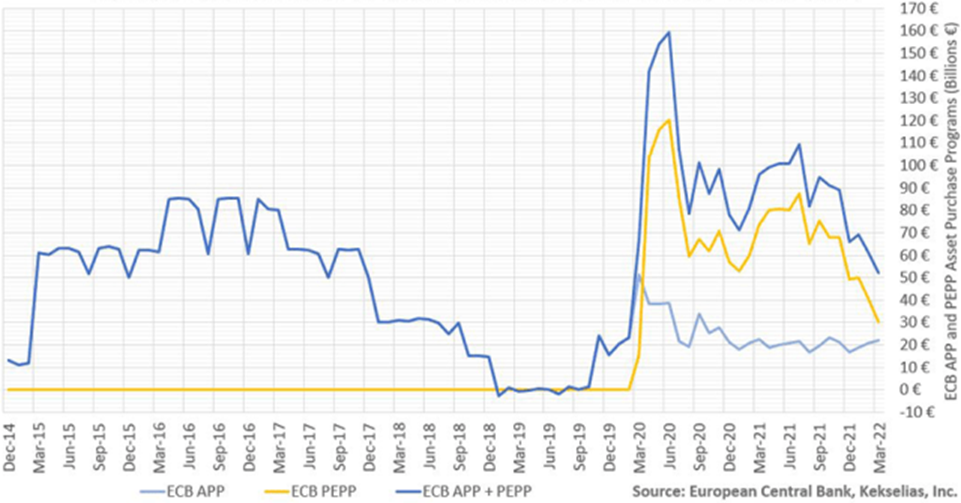

Monthly ECB bond-buying totalled €52 billion (about £44.3 billion) in March 2022 as the eurozone’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) reached 7.5% year-over-year (YoY). As the Fed slowed quantitative easing (QE) flows in February, personal consumer expenditures (PCE) were already at 6.4% YoY.

Despite QE’s role in suppressing long-maturity bond yields, the ECB’s 2022 purchases will fall to €40 billion in April, €30 billion in May and €20 billion in June, before halting ‘sometime’ later.

ECB Asset Purchase Programme (APP) and Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP)

QE programmes have anchored long-term global interest rates and co-movement between European and US long-term yields. Lael Brainard of the Fed’s Board of Governors recognised foreign QE’s ability to lower US long-term bond yields in 2017. Thus, expectations of rising Fed short-term rates amid ongoing foreign QE contributed to the inversion of the US 5s30s (spread between five-year and 30-year yields) Treasury yield curve.

Vineer Bhansali, the chief investment officer of California-based LongTail Alpha and author of The Incredible Upside Down Fixed-Income Market, also noted how policy affects the yield curve. Since central banks can influence all points on the curve through QE, the shape of the yield curve reflects the policy outlook rather than the likelihood of recession.

‘The first and most important signal that the Fed has distorted is the shape of the yield curve,’ noted Bhansali last month. ‘Yield curve inversions, in particular, are well known by market participants to be a reasonably good predictor of recessions. Historically, that is. Right now, the Fed owns so many Treasuries that it has the power to make the yield curve shape whatever it wants it to be.’

To add to Bhansali’s framework, an inverted yield curve embeds the expectation that rate hikes will slow the economy as inflation declines and disruptions ease, thus freeing central banks from policy constraints — a convergence toward pre-2020 ‘old normal’ — which would lower the hurdle of renewed QE to suppress long-maturity yields.

Conversely, an inflation regime change propelled by a more fractured world with scarcity-led reflation demands a reversal of balance sheet expansion or quantitative tightening.

The Fed’s guidance in March as to how it would unwind its balance sheet — at $95 billion per month — exceeded many bond dealers’ expectations.

Consequences of further fragmentation

As geopolitical instability disrupts resource allocation, the relative peace and prosperity of the past 30 years is being reassessed. Could the lack of major power rivalries over recent decades be the exception rather than the rule? And if the atmosphere deteriorates further, what will it mean for today’s globalised value chains?

This framework suggests the potential for supply-led inflation rather than disinflation. More unrest could fuel a de-globalisation process of supply-chain regionalisation and retrenchment that further boosts inflation. Yet, a less expansive supply chain may have benefits from re-expansion once disruptions cease and inflation falls.

In market terms, the current bond yields in developed countries cannot fully compensate investors should markets fragment further. BIS’s Carstens’ theory of an inflation paradigm shift leading to a monetary policy paradigm shift implies significant risks to long-maturity bonds, assuming a worsening geopolitical outlook and further supply-chain disruptions.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

By Victor Xing, founder and portfolio manager of Kekselias, Inc.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images/Thomas-Soellner