Chasing Tesla: how traditional carmakers are revving up their electric vehicle production

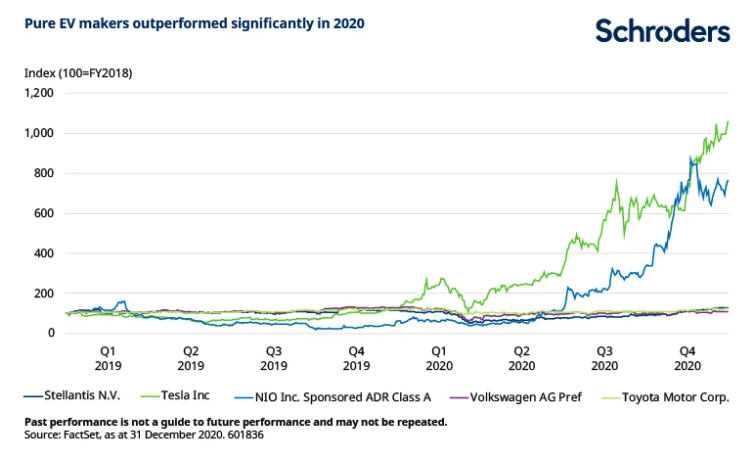

Equities generally had a strong year in 2020, but few parts of the market could match the runaway share price gains of the pure electric vehicle (EV) makers.

Tapping into investor (and day trader) demand for two popular themes – tech and sustainability – such companies became extremely highly sought after.

US group Tesla is the poster child for pure EVs, with China’s NIO its counterpart in Asia. The chart below shows how their shares fared over the two years to the end of 2020, in comparison to three more “traditional” automakers: Volkswagen, Toyota and Stellantis (formed by the merger of Peugeot with FiatChrysler). The contrast is stark.

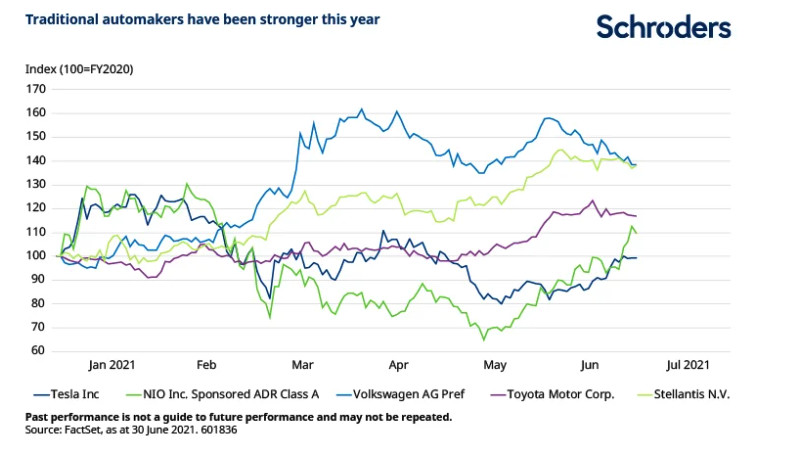

However, the old guard are fighting back. The chart below shows the share price performance of the same companies so far this year, and tells a rather different story.

Volkswagen is the top performer of the five over this time frame, helped by a sharp upward move in its share price in March. Meanwhile, the pure EV companies have languished as the prospect of rising rates has weighed on high growth stocks and the market has rotated into more lowly-valued areas.

It would seem that Volkswagen’s latest investor day finally convinced the market that it is a serious player in the EV space. After the “dieselgate” affair of 2015, Volkswagen has sought to change its spots by becoming a leader in EVs. This March, Volkswagen said it would deliver one million electric and hybrid vehicles in 2021, almost ten times the number in 2019.

The table below further highlights the disparity that had emerged by the end of 2020 between the valuations of the pure EV players (Tesla and below) and the traditional carmakers (Great Wall and above).

As we can see, the EV pure-plays were far more expensively valued compared to their expected 2021 revenues, or their expected 2021 car production. At year end, each car rolling off the production line at NIO was valued by the market at almost one hundred times as much as a new VW Golf (or e-Golf).

Part of the issue, as the table suggests, is that the pure EV manufacturers have become highly valued, but they don’t produce all that many cars (yet). Sales of pure EVs grew 39% in 2020, but this still only took them to a 4.5% share of the overall market (according to data from Canalys).

Fund manager and global sector specialist Katherine Davidson said: “The market has been paying handsomely for anticipated future growth at ‘new world’ carmakers. Meanwhile, ‘old world’ companies like Volkswagen have – at least until recently – been valued as though they were going out of business.”

Could this year’s uptick in Volkswagen’s shares, and downward moves for Tesla and NIO, be a sign that investors are reappraising the valuation gap between the pure EV players and the ’legacy’ carmakers? There are potentially several reasons to think so: the growing consensus that battery EVs are the “winning” technology; the efforts of traditional carmakers to focus on this area; and the possibility of entirely new entrants into the market.

Consensus building around pure EVs

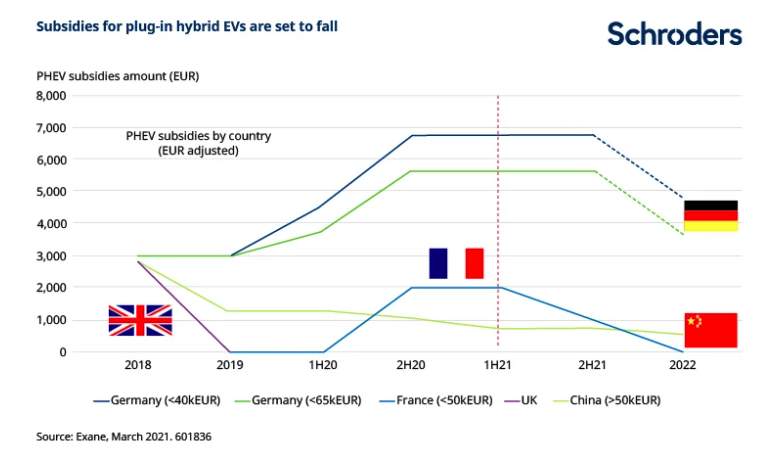

Firstly, the car industry now seems to be coalescing around the view that battery EVs, as opposed to hybrids or other fuel sources, will be the winning technology.

Katherine Davidson said: “Hybrids – even plug-ins – are increasingly being seen as legacy technology. They have been popular with consumers, given concerns over battery range, but that is lessening with improving battery technology and the build-out of charging networks.

“Plus, the tendency of consumers to drive hybrids mostly in conventional fuel mode means they’re nowhere near as helpful in terms of reducing CO2 emissions as the labelling would suggest, and regulators are wising up to this.”

“Costs are coming down very fast on the battery side, and customers are getting more comfortable with the technology”, Katherine Davidson added. “This means that other technologies, like hydrogen fuel cells, are a bit of a sideshow when it comes to private cars. The investments required to build a hydrogen refuelling network would be enormous, though governments in Japan and Korea are subsidising some projects.

“They are, however, a useful technology for heavier vehicles like trucks where the size of battery needed would make a pure EV impractical.”

Rodrigo Kohn, European Equities analyst, said: “The dynamics around the pure EV market have changed substantially just in the last couple of years. Batteries have become cheaper, vehicle ranges are improving, governments have come out with more subsidies, and the cost of production is coming down.

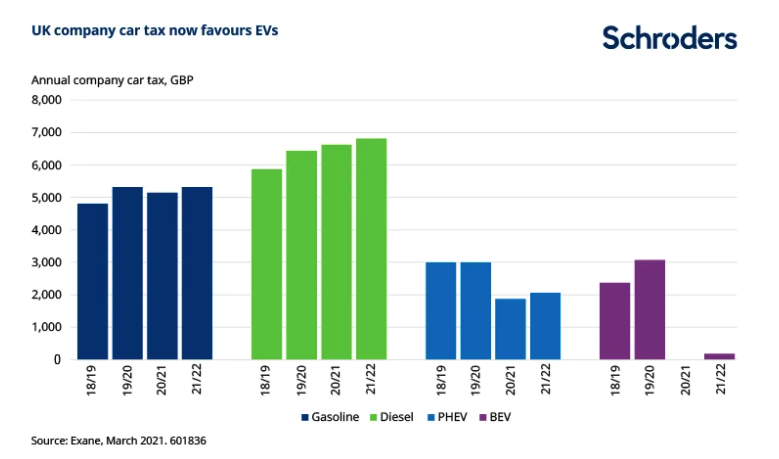

“For a consumer buying a car on a two-year lease, as is common in many developed markets, the cost is often less than a combustion engine vehicle or even a hybrid, especially for company cars.”

Increasingly stringent regulations are another factor, especially in Europe where car companies face fines if the average emissions for their fleet exceed 95g of CO2 per kilometre.

Katherine Davidson said: “The potential fines companies face for exceeding emissions limits could be more painful than selling EVs at a loss. The demand for EVs in Europe is a mixture of ‘pull’ from consumers and ‘push’ from regulators.”

It’s a slightly different picture in Japan, according to Japanese Equities analyst Tetsuo Iwashita: “Hybrids remain popular in Japan, largely due to the highly efficient and attractive models offered by Toyota. Indeed, even in Norway – where EVs outsell hybrids and internal combustion engine cars – a Toyota hybrid is a popular choice for a second car.

“In addition, the carmakers are large employers and the Japanese government is wary of encouraging an abrupt switch to pure EVs as this could cause significant disruption to the workforce. This means we could see a slightly slower transition towards pure EVs. Japan is set to phase out new sales of internal combustion engine cars by 2050, compared to 2030 in the UK, although this could change if the carmakers themselves speed up development of EVs.”

Another factor is that fossil fuels still dominate electricity production in Japan. Switching to EVs therefore doesn’t have the same overall impact on emissions as it would in countries with a higher proportion of electricity from renewable sources.

Discover more at Schroders Insights or click the links below:

– Why is digital infrastructure so important for real estate investing?

– What does China’s stock market meltdown mean for investors?

– Why emerging markets could be the next digital frontier

Conventional automakers catching up

Given the growing consensus around pure EVs, the conventional automakers have no choice but to re-focus their efforts on this area.

Energy transition fund manager Alex Monk said: “Without Tesla, it’s unlikely that the EV and clean mobility industry would be where it is today. But the conventional carmakers aren’t just sitting back and watching. Volkswagen is not only ramping up EV production; it’s also building out battery capacity as well. Toyota is another that has been active in battery research and development.”

Indeed, while hybrids continue to be a success story for Toyota, the company is innovating when it comes to EVs, as Tetsuo Iwashita explains: “Toyota has been working on the development of solid-state batteries, as opposed to the lithium-ion batteries used in most EVs currently. Toyota holds over 1,000 patents relating to solid state batteries. It is targeting 2025 as the release date for a solid-state battery EV and that is the point when we could really start to see EV adoption take off in Japan.”

Cars with solid state batteries are expected to take less time to charge and have twice the distance range per charge. The batteries themselves have a higher energy density relative to their weight and a lower risk of fires.

While some companies are focusing on their own innovation when it comes to EVs, others have joined forces. Ford will use VW’s new EV platform to produce all its European models, leaving it to focus attention on electrifying its highly profitable pick-up trucks in the US. The merger of Peugeot with FiatChrysler, forming Stellantis, is another example.

Rodrigo Kohn said: “Peugeot is a very efficient producer and its release of the mass market e-208 model has allowed it to steal a march on competitors and gain market share. By contrast, Fiat has been much less efficient and in recent years has been slow to refresh its fleet and develop new technology. It’s underinvested in Europe, focusing on the more profitable US market with the Chrysler brand. But both companies have enormous production facilities in Europe. The merger brings greater scale and should make the development and production of new vehicles more efficient and economical.”

The arrival of these traditional carmakers to the EV market could pose a challenge for the likes of Tesla, but also creates investment opportunities.

Alex Monk said: “These companies, simply due to their size, will sell far more EVs than Tesla can. It will take time for these conventional automakers to transition their business models but the valuation disconnect between pure-play firms like Tesla and the conventional players is enormous.”

Low barriers to entry

A third reason why the pure EV players are facing greater competition is that the barriers to entry for new EV manufacturers are low. EVs have far fewer moving parts than a traditional internal combustion engine car so they are simpler to manufacture. What’s more, the most important components – the battery and power electronics – can be bought ‘off the shelf’ from any number of sophisticated suppliers.

These low barriers to entry, combined with the market’s appetite for all things tech and sustainability-related, means there are plenty of new companies with designs on the EV market.

Lack of customer loyalty is another factor in the success of new entrants.

Katherine Davidson said: “The experience in China suggests that customers are receptive to new brands, contrary to the received wisdom that consumers will be risk-averse and brand loyal when buying big-ticket (and potentially lethal!) items. The EV transition seems to be coinciding with a greater focus on customer-centric design, slick operating systems and ‘infotainment’ options – making the car more like a smartphone.”

Some of the new entrants in the market are entirely new companies focusing exclusively on electric vehicles. Others are existing companies turning their hand to EVs. One such is Foxconn (HonHai), better known as the assembler of Apple’s iPhones, which has signed an agreement with Fisker to co-develop and manufacture an EV. Meanwhile, rumours persist that Apple itself could enter the EV market.

Rodrigo Kohn said: “It seems likely that there will be non-traditional entrants into the market but the question remains over the scale of their ambition. Will they really want to compete with the incumbents, given the huge amount of capital they would have to spend to do so? Companies like Google and Microsoft have been mooted as potential EV players too, but they would perhaps be more likely to create a small fleet that can gather data to enhance their software products, and then sell these products to the OEMs.”

On the other hand, the addressable market is huge. Katherine Davidson said: “The growing software content in a car and the gradual shift towards autonomous driving has the potential to fundamentally shake up the competitive set.”

Tetsuo Iwashita added: “Tesla has so far had an advantage over the traditional carmakers in terms of its software; it’s probably two to three years ahead of the likes of Volkswagen and Toyota. But can it retain this advantage, especially if Apple and others enter the field? We’ve seen rapid change in the industry in recent years and the next few years will also bring enormous change.”

Can the car market grow?

Governments around the world are providing incentives for consumers to switch to EVs as a key part of their strategy for achieving the Paris climate goals, and penalising carmakers who drag their feet. EVs are therefore making up an increasing part of the automotive mix, and their share will grow further.

Estimates from Statista project EV car sales to be 26% of the overall global car market in 2030, rising to 72% in 2040 and 81% in 2050, though prior estimates have been repeatedly revised higher as EV adoption has accelerated.

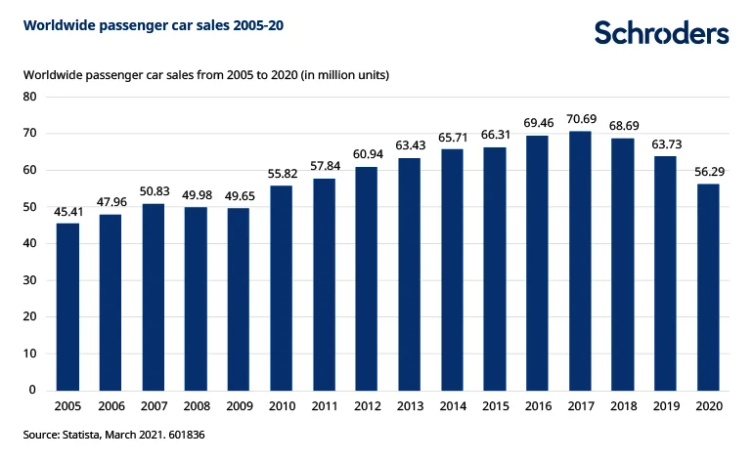

But what of the growth of the overall car market? The chart below shows that, while 2020 was clearly a peculiar year, car sales have been falling since 2017.

“In terms of passenger car sales, developed markets may have already peaked”, said Katherine Davidson. “China is no longer unchartered territory and growth from here will come from less developed emerging markets. They tend to be dominated by small cars, low average selling prices and poor infrastructure which is particularly problematic for EVs.”

Developed markets could even see a more protracted decline in car ownership.

Katherine Davidson said: “Ageing – or even shrinking, in much of Europe and Japan – populations could put pressure on car sales, as could car-sharing schemes which were growing in popularity before the pandemic. There may also be lower demand from commuters if work from home trends persist – maybe you only need one car per household instead of two. Urban planning is also increasingly hostile to vehicles, with governments encouraging people to walk, cycle or use public transport.”

That said, the timing of any reduction in overall car ownership in developed markets remains very uncertain and would differ by geography.

Rodrigo Kohn said: “Europe’s higher population density may mean ownership drops off faster than in the US, but it’s hard to predict when that would happen. Meanwhile, take-up of EVs in Europe has increased dramatically and there are some signs of overall demand trends being more resilient since the start of the pandemic.”

What does this mean for investors?

The transition to EVs is occurring rapidly. Battery technology, driving range and access to charging points are all improving. Sweetened in most markets by government subsidies, these improvements are helping to make EVs an increasingly popular choice for consumers. However, the possibility that the overall market for cars could remain flat or even decline in some geographies means investors will have to choose carefully to select the winners of this transition.

Being first off the mark with any new technology isn’t always a recipe for long-term success. Tetsuo Iwashita said: “In Japan, Mitsubishi and Nissan were the frontrunners in EV development 15 years ago. They were very innovative but the cars they produced weren’t popular with consumers: they were seen as too small and inconvenient to charge.” But on the other hand, carmakers who are too slow to recognise the transition taking place may find they lose market share irretrievably.

Car companies, and those who invest in them, will need to plot a careful course through the rapidly changing landscape of technological advances, consumer tastes, and ambitious government targets.

Tesla’s Elon Musk may be the “technoking” of the EV sector now, but there are plenty of others seeking to take that crown.

– For more visit Schroders insights and follow Schroders on twitter.

Topics:

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.