Are we working more than ever?

Furlough and working-from-home have dispersed workers into a diverse range of new working patterns. Social media is filled with anecdotes from workers who start their day late and finish early but still get more done by virtue of not having to commute to an office. There are those who have already returned to and embraced their return to the office, thankful to be away from the distractions of home. And of course, there are those who never stopped working, most notably essential workers and healthcare professionals.

Events of 2020 and 2021 have inevitably led to talk about the nature (and location) of work being changed forever. Coronavirus is a black swan events that is beyond what is normally expected, severe in impact and extremely rare. But rather than fundamentally changing how and where we work, the black swan of 2020 and 2012 may instead simply be accelerating a pattern in our working hours that actually started 150 years ago.

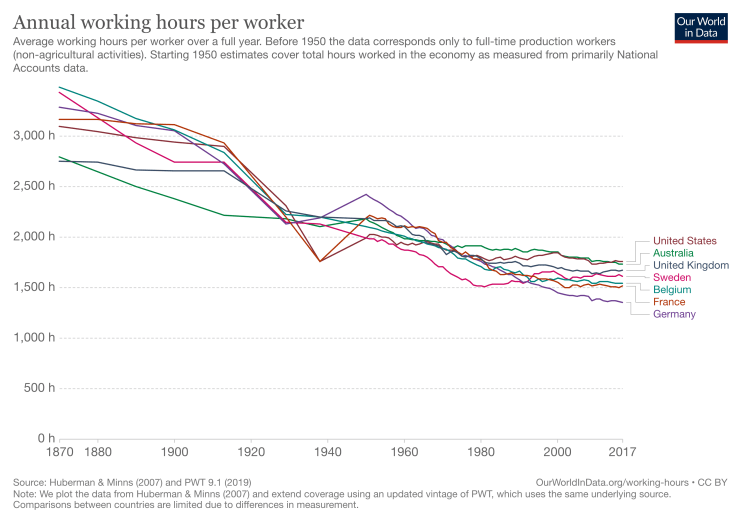

Compared to every year that precedes us, today we work fewer hours each day, fewer days each week, and fewer weeks each year. In fact, research by the economic historians Michael Huberman and Chris Minns shows that average working hours have declined dramatically for workers in early industrialized economies over the last 150 years.

In 1870, workers in most Western countries worked more than 3,000 hours annually — equivalent to 60–70 hours each week for 50 weeks per year. Today those working hours have been roughly cut in half. In Germany, annual working hours have decreased by nearly 60% — from 3,284 hours in 1870 to 1,354 hours in 2017. And in the UK working hours have decreased by 40% since 1870.

Whilst falling working hours can be traced back to 1870, it was between 1913 and 1938 that the trend accelerated amidst the powerful socio-political, technological, and economic changes of World War I, the Great Depression, and the lead-up to World War II. There was a small climb in working hours during and after World War II, but then the decline in working hours continued for many countries, albeit at a slower pace than the early 1900’s.

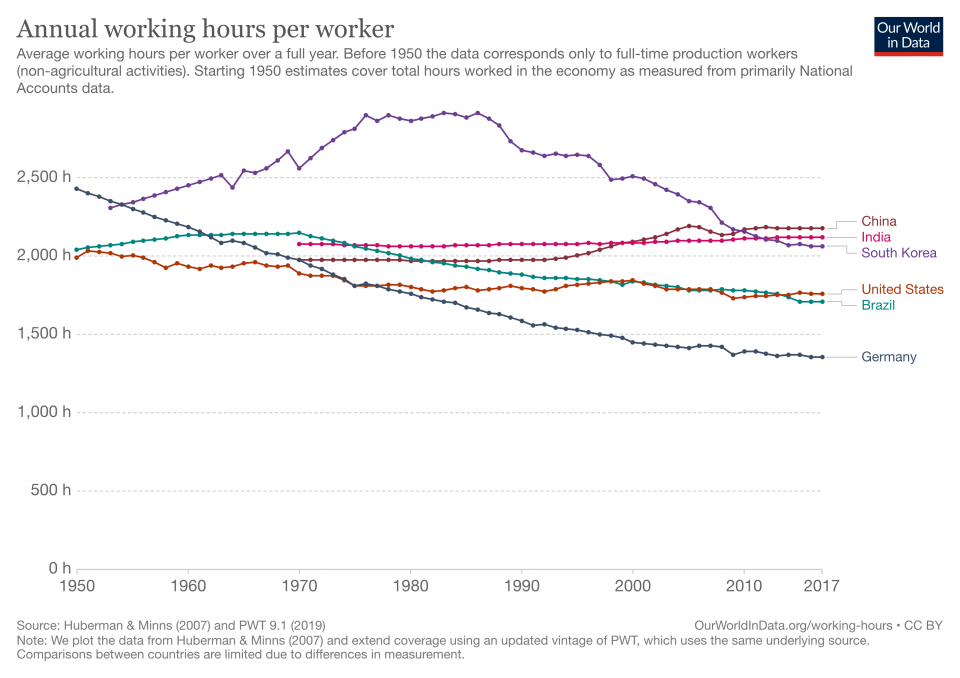

As the wider world has industrialized and developed over the last 70 years, there has been a continued decline in working hours. There have also been large differences between countries. For some countries, such as Germany, working hours have continued their steep historical decline; whilst in the USA, the decline has levelled off in recent decades.

In some countries we see an inverted U-shaped pattern in working hours. In South Korea, for example, hours rose dramatically between 1950 and 1980 but have been falling again since the 1980s. In China, working hours rose in the 1990s and 2000s before levelling off.

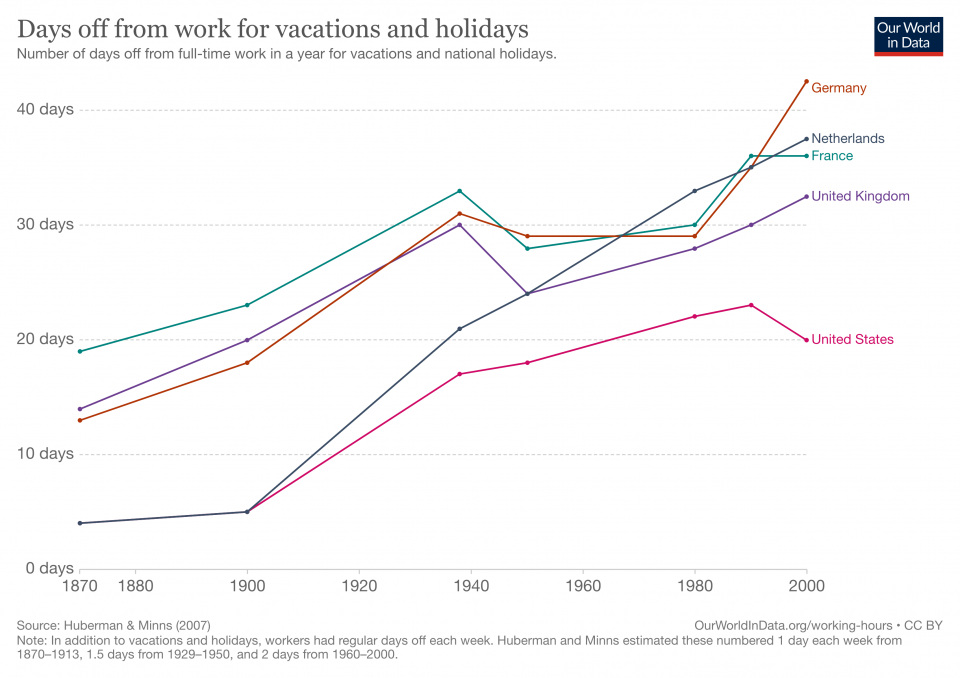

By 1940 the typical work schedule was 8 hours a day, 5 days a week, but the year-long average working hours were reduced further by relatively new innovations to the pattern of work including vacations, holidays, sick days, personal leave, and earlier retirement.

Having two days off for the weekend became typical in the 1940’s. And taking days off for holidays increased everywhere by the year 2000. In The Netherlands in 1870 workers typically had just four days off for vacation. By the year 2000 the average had climbed to 38 days.

The average worker in a rich country today really does work substantially fewer hours than the average worker of 150 years ago. Whether the aftermath of Coronavirus will accelerate this trend remains to be seen. Perhaps more likely is that artificial intelligence and automation will start to reduce the burden of work that falls upon humans, allowing economies to become even more efficient and workers to enjoy even more time at leisure whilst living longer lives.

To cater to this future, in 2019 Bill Gates proposed a ‘robot tax’ to slow down the transition toward automation so that society can cope with the transition and to replace the income tax lost as robots replace workers. In 2020 technologist Tej Kohli similarly proposed a tax on the data centres that will be required to power a “revolution” in artificial intelligence.

Regardless of the primary catalyst, it seems certain that workers will be working less in the future. Whether society is ready for it is another question altogether.

This post is based on an article first published by Our World In Data at: https://ourworldindata.org/working-more-than-ever