What is your belief system?

Everyone has a belief system that drives their behaviour.

To be successful, we should understand the major beliefs that influence our work. If we believe that equity markets are efficient, for example, we might not choose a career in active management. If we believe that money is the root of all evil, we might not choose an investment career at all.

Our beliefs are not always at the forefront of our consciousness — this is what makes them challenging. We are perplexed when asked outright about our ‘beliefs operating system’. It is always running in the background, like Windows on a PC, but we don’t actively acknowledge it. If our PC gets a virus that attacks the operating system, however, then it could slow down or completely disable our computer.

Like computers, people can have viruses — negative beliefs — that attack their operating systems and make them less effective.

Positive beliefs, such as “I’m a talented and capable person,” support our work efforts and should be encouraged. Negative beliefs — “Only suckers put in extra time at work” — however, don’t serve us well.

We can’t surface and evaluate all our beliefs. We have thousands of them and many are irrelevant. The key is to identify and prioritise those that affect our work. We need to address any negative ones and replace them with healthier alternatives. We need to substitute those that don’t bring value for those that do. For example, many active investors believe, “We can beat the market by hiring smart, hardworking people.” Evidence suggests that superior performance requires more.

Another key investment belief involves our investment edge. If good performance requires more than smart, hardworking people, what is our edge? What gives us our competitive advantage? Some might say that a competitive edge connotes a strategy, but beneath our strategy lies a belief about how the markets and investors work.

To illustrate, certain investors believe that quantitative methods are superior to fundamental analysis. Others believe that a mix of both is optimal. CIOs and their investment teams should surface and formalise these beliefs. I once worked with a fundamental equity team that included one quantitative analyst. The quant was convinced — his belief — that fundamental value analysis added nothing over and above what the quant screens delivered. Eventually, he and the team parted ways. The two belief systems were incompatible.

So, what beliefs are important to investment professionals? If you are an active investor, you should be clear about your market and investing beliefs. For example:

- How efficient is the market you trade in?

- What is your competitive edge?

- Is collaboration with teammates important to success?

- Is investment skill learned or innate? Can you teach it?

- Is superior performance achieved with dedicated teams or centralised research?

- What is the maximum number of companies an analyst can follow?

- Are decisions best made by one person or a group?

- Will diversity on your team improve performance?

This list is not exhaustive, but it gives a feel for the exercise. Distinguish and address the key beliefs that underlie your investment philosophy and process. Debate them and then formalise them.

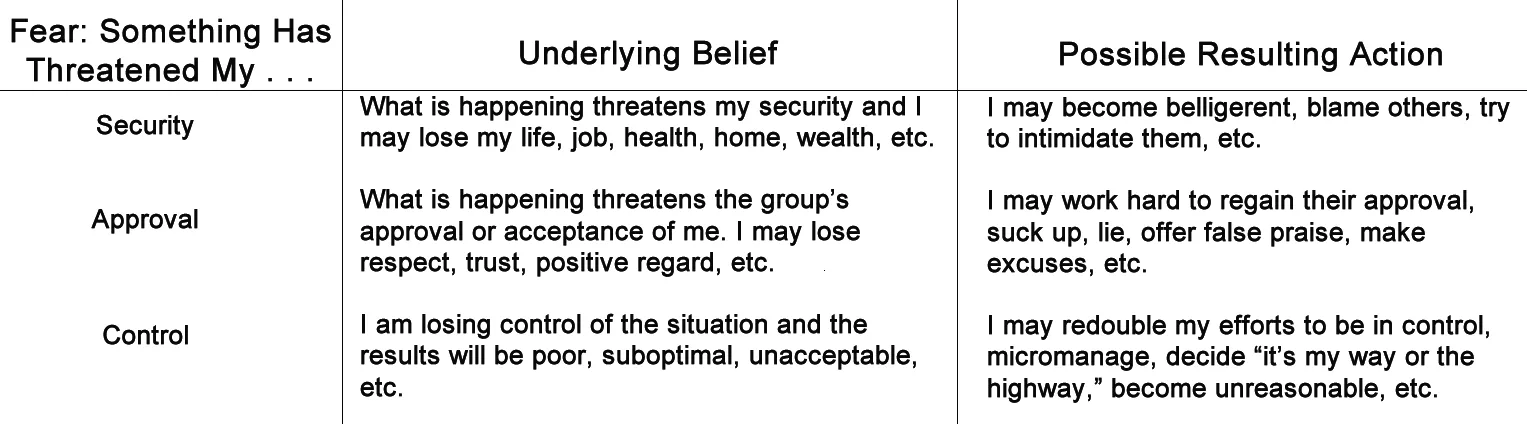

Other beliefs that are useful to examine: those that cause emotional drama. Three major factors drive much of this behaviour: security, approval, and control. When we feel that one of these is threatened, we become fearful and reactive in a predictable way: dramatically. The table below shows the beliefs that my firm has uncovered when coaching investment professionals.

The better choice is always to remain level-headed and accept what is happening so that you can respond appropriately. Unfortunately, we often get sucked into our beliefs and react in a suboptimal way: whether bullying, accommodating, or micro-managing.

We all experience these fears to varying degrees, often leaning toward one in particular. In my case, it’s approval. I’ve learned that I have a deep-seated belief that the way to successfully navigate relationships is to win people over as friends. Sometimes it’s useful. I’m not arguing against friendliness, but often it’s irrelevant. And ineffective.

Years ago I asked an investment professional if he liked his boss. He looked at me with genuine confusion and said, “Why would that matter?” My own belief system skipped a beat. I thought that approval mattered to everyone. Aren’t all of us concerned about friendship with our bosses: Do they like me? Do I like them? Since then, I’ve had to disabuse myself of that belief to be more effective.

But the opposite belief can be just as harmful. If you think that professional relationships don’t matter, you can find yourself marginalised if that is what the team values.

In either case, understanding our own operating system — and those of the people around us — is important.

If we can isolate the beliefs that are truly influential in our professional work, we can improve our success rate.

We must always ask ourselves, “What do I believe is true? And how does this affect my decisions and behaviour?”

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.