Farage wants to reawaken the Brexit mob with a ragbag of populist policies

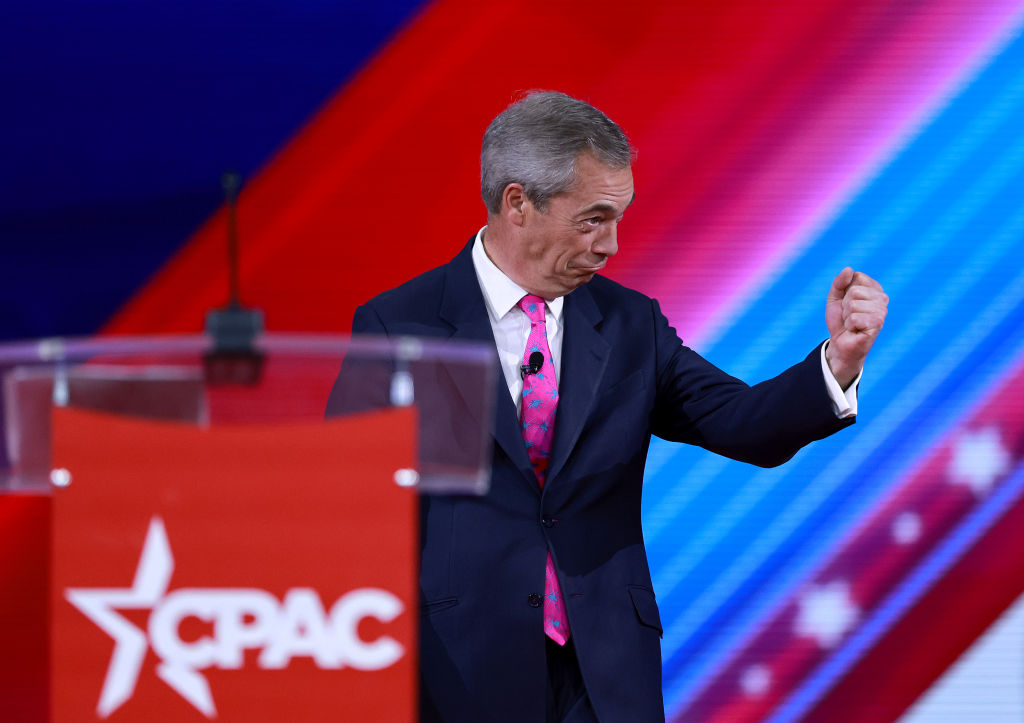

The veteran political journalist Michael Crick recently described Nigel Farage as “the most significant politician of the century so far”. This might seem like a blatant piece of liberal-baiting clickbait, given that Farage has stood for election to the House of Commons no fewer than seven times without success, but Crick is neither a fool nor a hyperbolist. Farage genuinely changed the terms and focus of the debate over Europe, and placed the issue of immigration, especially across the English Channel, beyond the narrow confines simply of cranks and racists.

Farage also seems to have retired more often than Sinatra, but last week he wrote in the Telegraph issuing a message of defiance to his critics. The party he founded in 2018 as the Brexit Party, renamed last year Reform UK, will field candidates across the UK, and will set its face against electoral pacts with the Conservatives or anyone else. They are out to win, not merely to enable.

This is not all about Nigel, we are assured. Although he co-founded the party with financial trader and hotelier Catherine Blaiklock, he is merely its honorary president, the leadership being held by the ambitious but often implausible Richard Tice. Farage admitted that he “communicates regularly” with Tice, but is loath to portray Reform UK as another Farage vehicle.

Ever since Reform UK took over the corporeal existence of the Brexit Party, it has been in search of an animating spirit. It has tried on the clothing of lockdown scepticism, support for low taxation, an increase in direct democracy and opposition to net-zero carbon emissions, but nothing has quite given it the traction it wants. Now it returns to familiar territory, with Farage installing himself as the watchdog of Brexit. In his Telegraph peroration last week, he warned “I didn’t spend 25 years of my life battling to secure a seemingly hopeless cause only to watch Jeremy Hunt give it away”.

Farage was always about Brexit, and now, the UK has left the European Union and no serious body of thought really imagines we will be seeking readmission in the near future. Is he merely seeking to refight old battles and feel the sun of his glorious summer on his face again? He is certainly bullish about Reform UK’s prospects: he points out that the party has been polling as much as 9 per cent nationally of late, modest enough but toe-to-toe with the Liberal Democrats, and that 40 per cent of Conservative votes would consider voting for a party led by Farage (which Reform UK currently is not).

But the shape of the Brexit debate has changed, and while immigration is still very much a live issue in constituencies around the country, it evokes a different kind of antagonism. The European Union served a useful purpose: it was an outside entity for which we could blame all our problems on. Now we have pulled ourselves from its clutches, our immigration debacle – both on the question of asylum and low-skilled workers – is all of our own making.

Nigel Farage is 58. A serious road accident, testicular cancer and a plane crash have not slowed him down, and he remains, whether one likes it or not, one of the most approachable and relatable politicians in Britain.

Perhaps he also sees himself as a man of destiny. He finally delivered what some thought was an undreamable dream and, while he is easily moved to ruddy-cheeked outrage, it is obvious that nothing gives him the existential joy and satisfaction of hostility towards the EU institutions and Remain voters.

Some of this leaves an unpleasant taste. Many people will not be relieved to see Farage as some kind of independent-minded arbiter of loyalty to the cause he has worshipped for so long. And his rhetoric about the failures of the Conservative government, the disappointment of the electorate and their disenchantment with the “usual suspects” plays to a certain crowd who often bemoan “the media”. But Farage knows, better than anyone else, that disenchantment and alienation are among the most powerful political motivators, rarely in a good way.

British politics is due a little bit of change. But the resurrection of Farage as our Brexit inquisitor and pastor, keeping us true to the one faith, is not that change. Reform UK’s manifesto is a ragbag of populist chants placed like baubles on the Brexit Christmas tree. Let us not chase the banality of soundbites and the echo chamber of mutual reassurance. He might be good company, but we can do better than this.