The Long View: The robots are coming – but the power of human ingenuity will save our jobs

I FOR one don’t welcome our new robot overlords. Don’t get me wrong – I’m all in favour of the liberating potential of new technology. I’m also conscious that worries about jobs lost to mechanisation have a history of being misplaced: the jobs go but new and even better-paying ones appear elsewhere.

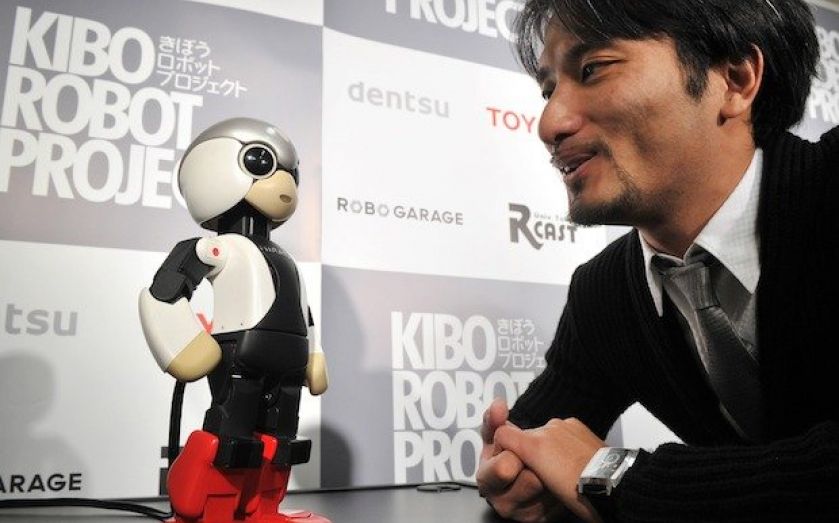

What’s worrying right now is a strain of fatalism among the world’s intellectual elite. Seeing the impending arrival of a host of robots and expert systems able to perform tasks previously only possible for skilled humans, they predict a future in which the middle of the jobs market becomes hollowed out, providing opportunities only at the very top – and bottom – of the heap.

Don’t think this trend can’t affect you. The probability, for instance, that accountants and auditors will see significant job losses to computerisation in the next twenty years is startlingly high. It is calculated at 0.94 in a 2013 paper on the future of employment by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne, which also places the probability for economists at an unsettling 0.43. Financial journalists can’t rest easy either – firms like Narrative Science are already invading our territory.

All this is why, at the World Economic Forum in Davos earlier this month, Google chairman Eric Schmidt declared that the loss of middle class jobs to technological advance would be the defining issue of the next thirty years. Yet when it came to solutions, he didn’t appear to have much more to offer than better technology.

That shouldn’t be much of a surprise. In a situation like this, we need the very opposite to Davos thinking. A cosy elite insulated from the crisis, and which discusses it only as a kind of abstract intellectual puzzle, is hardly a likely forum for useful insight.

But the tech companies themselves may demonstrate part of the answer – not in the brilliance of their gadgetry but in the way they manage their businesses.

Tech firms in recent years have developed management styles antithetical to the Davos mindset. Firms like GitHub, Valve and Zappos.com have created significant value by shifting from a top-down to a style of organisation where the best ideas can surface wherever they come from.

It is a reminder that there are huge efficiencies firms can find beyond the technological. Such reforms work in businesses of all kinds: the book Freedom Inc by Brian Carney and Isaac Getz discloses similar success stories at firms like Harley Davidson, WL Gore (of Gore-Tex) and Sun Hydraulics.

Technology is a great enabler. But it can make us lazy. Riding on the back of Moore’s law into an ever-faster digital future, we forget the economic power of human agency.

Unchaining ourselves from top-down systems has already done so much to improve the world’s economic prospects. It is easy to miss the potential that remains, in fields from business to education. The robots are coming. But if we stop treating one another like robots, we can discover more human ways to add value while the robotic jobs disappear.

Marc Sidwell is managing editor of City A.M.