The Japanese general election: Shinzo Abe has history on his side

The Japanese proverb “nanakorobi yaoki” roughly translates as: fall over seven times and stand up eight. It urges perseverance, and may be some comfort for Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe ahead of this Sunday’s election.

It has been a busy few months for Japan watchers – fresh QE, another slide into recession, and the calling of a snap election in which Abe hopes to strengthen his mandate. It’s a good time to reflect on where the country might go next.

When interest rates are near zero, central banks can only stimulate demand by raising inflation expectations. Paul Krugman called this a “credible promise to be irresponsible”. But if it works, it gives central banks something that they don’t want. They want to convince people that inflation will be above target in the future. But when the time comes, it won’t want this. Investors, households and businesses know that, so don’t believe the central bank in the first place.

As tricky as this elaborate bluff sounds, Japan did manage to achieve it in response to the Great Depression. While the US and much of Europe enjoyed a boom in the 1920s, Japan grew at less than 1 per cent per annum between 1921 and 1929. Its economy suffered regular shocks (not least an earthquake that flattened Tokyo) and financial panics. Japan’s return to the gold standard in 1930 was timed terribly, coinciding with a deepening of the Great Depression, and the yen was left significantly overvalued.

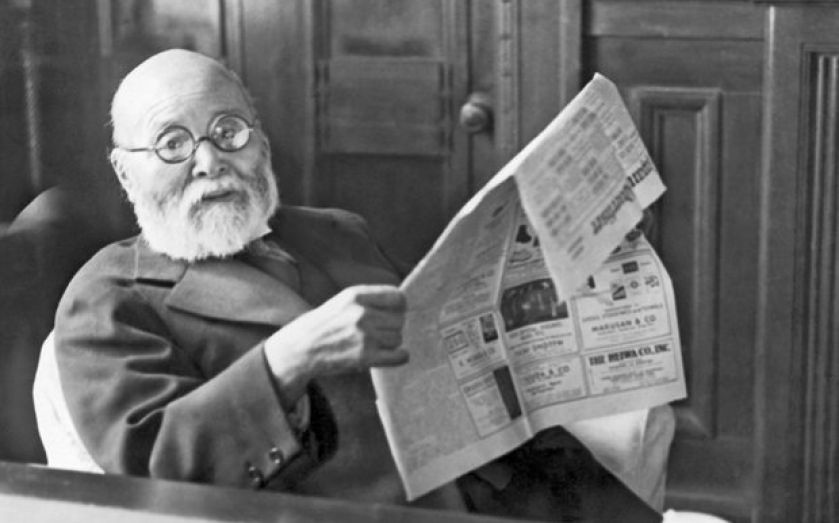

An ensuing debacle in Japan’s management of the gold standard resulted in the government resigning in 1931, bringing the Seiyukai party into power, with Korekiyo Takahashi as finance minister. He immediately suspended the export of gold, and pushed down the exchange rate to help boost inflation expectations.

He then embarked on a number of policies to eschew expectations of deflation and boost growth. In response to this huge fiscal and monetary easing, inflation rose to 7 per cent in 1932 and then 12 per cent in 1933, while GDP was up to 7 per cent and 8 per cent respectively.

Takahashi’s actions were revolutionary. His peers around the world thought countries’ primary goals should be balancing budgets and avoiding abandoning their exchange rates. His policies would have been seen as the height of irresponsibility at the time. But they were incredibly successful, and a testament to the power of monetary and fiscal policy to shift expectations, even in a deep slump.

The historical parallels between then and now are clear. Aggressive monetary easing, coordinated with fiscal policy, can shift people’s inflation expectations and boost growth. This is why Abe’s bold strategy has credence – theory and history are on his side. But this requires political will, relentless and carefully crafted messaging, and the understanding that sometimes being “responsible” is actually grossly “irresponsible” when it comes to escaping from the economic doldrums.

We should expect further easing from the Bank of Japan, and for Abe to continue to prioritise growth. But he’ll have to pick himself up a few times along the way.