Grapes of wealth

Wine investment requires patience and special knowledge and is not a way to make a quick profit — you need to be in it for the long run, says Toby Walne

Wine lovers can savour a fine vintage not just in a glass but also as a tasty investment. Despite the wine market being notoriously difficult to predict, over the past decade the best vintages have grown in value by an average of 5 per cent a year.

Premier Bordeaux wines have soared by up to 36 per cent in value over the past 12 months with the top 30 clarets growing by an average of 8 per cent in value.

Justin Gibbs, a director of Liv-ex, which tracks the wine market, says: “There is no doubt this has been a very good year for wine investment.

“However, it is important to be wary of short term rises and only invest as a wine lover. If you feel pressured into joining the market you are making a mistake.”

Gibbs believes fine vintages can offer an excellent long term investment but points out recent speculative punts could leave a bad taste in the mouth.

Proposals allowing wine investments in Self Invested Personal Pensions (Sipps) from next April have fuelled a price boom but the rules have yet to be rubber-stamped and Sipps providers have not yet signed up to offering tax-free wine investments within a portfolio.

With demand for top wines always limited, however, Gibbs believes that it is unlikely an investment bubble will burst but rather that growth rates will slow down.

Over the past decade annual wine consumption has doubled to 30 bottles per person in Britain, creating a knock on effect with investments. New rich wine buyers from Russia and China have also helped push up prices at the top end of the fine vintage market.

France’s famous Bordeaux wines are the best bet when it comes to investing in wine and they account for the vast majority of the market. The biggest guns to look out for are the five first growths — premiers crus — of HautBrion, Lafite, Latour, Margaux and Mouton-Rothschild.

These are deemed the best blue chip names for investing along with Cheval Blanc, Ausone and Petrus.

Other great producers include superseconds Pichon-Lalande, Leoville-Las Cases, Cos d’Estournel, Lafleur, Montrose, Leoville Barton, Palmer, Lynch Bages and Angeles.

The year the wine is produced also plays a crucial factor in values as the weather dictates the final quality of wine. Classic past vintages include 1982, 1989, 1990, 1995, 1996, 2000 or 2003.

At the highest quality level France also offers red and white burgundy, Rhone, Alsace and champagnes that have also produced winners over time.

The top end New World wines rarely succeed as investments, though some producers in Australia and California have started to attract investment.

Wine lovers typically put aside between £500 and £3,000 a year for investing but should ensure it is never more than 5 per cent of an investment portfolio.

The best way to boost potential profits is to take the high risk of buying the wine before even bottled — en primeur — in spring.

An army of wine critics and merchants descend on Bordeaux in March and April to sample young wines while still in the bottle.

Investors must therefore rely heavily on the quality of wine merchant advice and not just their own nose for a good tipple when picking a classic vintage.

Jasper Boersma, a wine merchant for Bibendum, says: “Anyone can take a punt on a vintage but unless you have ten hours a day to spare to study wines it is prudent to seek expert guidance on what to buy.

“Do not rush headlong into buying a wine without thinking first. You may make some money but the primary concern is to enjoy the experience.”

Bibendum is among the leading wine merchants in London. Others include Farr Vintners, Premier Cru and Berry Bros & Rudd.

Unfortunately, the wine investment market is unregulated and littered with rogue traders. When considering a wine merchant first check on the website www.investdrinks.org, which has a list of dubious traders.

The Wine Advocate magazine also has a huge impact on whether a fine glass of wine is just a great drink or a superb investment as well.

No matter what other tasters may think, if its influential American wine connoisseur Robert Parker gives a wine his personal thumbs up values will soar.

Parker marks everything he sips out of 100. Anything over 96 is classed as “an extraordinary wine” and turns a fine drink into a superb investment winner.

However, Boersma points out that you have to second-guess his views before they are published if you are to hit the wine jackpot.

The biggest success story over the past 12 months is Lafite Rothschild ’82 and Latour ’82 which have both soared 36 per cent in value, according to Liv ex. A case of the Lafite Rothschild now fetches £5,800 — more than £480 a bottle, while Latour is £6,200 — about £516. When the wines were first bottled you could have purchased a 12-bottle case of either for £275, just over £22 a bottle.

You must also make sure any investment is stored in a bonded warehouse, ensuring that no VAT or duty will be paid on your wine until or unless released. The wine can avoid tax when traded if it remains bonded. By being bonded the owners should also get a certificate of ownership, which offers proof of ownership and history when traded later on.

Bonded warehouses will store the wine safely in dark and cold areas, which are temperature controlled and free from any vibrations.

A fine wine can be ruined if stored for a long time in the fluctuating atmosphere of a kitchen or living room — it may also offer a temptation to uncork as a drink.

Storing wine under bond will typically cost between £5 and £15 per case a year and this should include insurance against loss or damage.

Most wines are made to be drunk within a few years but if you buy the very best — particularly if in big magnum or double magnum bottles — there is no reason why your investment shouldn’t last 40 years. A top wine should typically be stored at least 10 years as an investment opportunity although jumps in the market may mean trading within a year is possible.

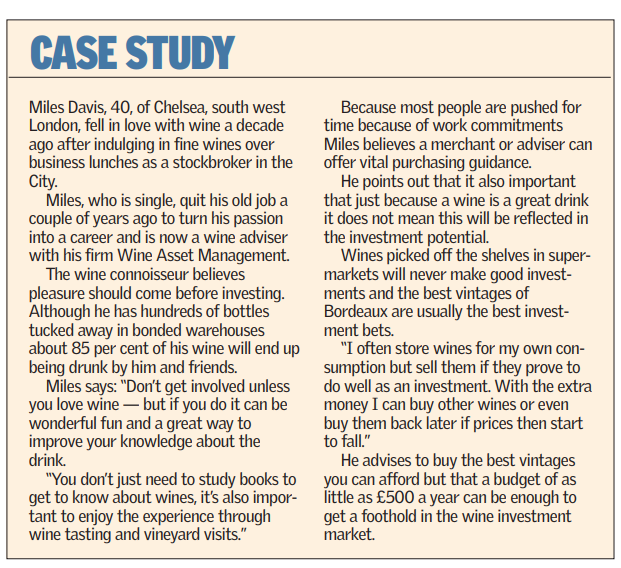

“Buying a fine vintage is far easier than selling it. The typical option is to sell it back to the merchant but you can also take it to auction yourself,” says Boersma. If a merchant purchases the wine they are likely to take a cut of at least 10 per cent of its market value. Auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s also demand a seller’s premium of about 10 per cent. The taxman regards wine as a “wasting asset” so is not normally liable for capital gains tax unless it has been collecting dust for at least 50 years.