End of Bank of England £800bn bond buying scheme poses headaches for Treasury and taxpayers

The magic money tree is shedding its leaves.

Over a decade of cheap cash propping up the global economy has been toppled by a once in a generation inflation problem.

QE was a necessary response to the batch of shocks ricocheting around the global economy since 2008. Now it’s shifted into reverse.

But how did we get here?

Central banks across the world created new money to support the financial system after the 2008 banking crash caused credit to dry up.

The world’s largest lenders were burnt from handing out money to people who, once the economy experienced a downturn and their incomes were knocked, couldn’t afford to repay their debts.

Fellow banks also became very weary of extending handing money to each other. The global financial system seized up.

The likes of the US Federal Reserve, Bank of England and European Central Bank slashed their official interest rates in a bid to get money flowing again. Those moves were supported by QE.

QE supports official deposit rates falling by putting downward pressure on rates in international debt markets by jolting demand. Bond prices and yields move inversely, so when demand rises, rates drop.

Central banks buy government debt hoovered by lenders in exchange for pumping up their reserves.

Government debt is an instrument that’s contained in financial markets, though it is highly liquid, meaning it can be exchanged for cash immediately. But a bank would never lend an individual a gilt or a treasury.

When banks have a greater amount of cash on their balance sheet held at the central bank, it pushes the amount of money they need to hold in reserve above the necessary threshold, freeing up money to distribute to businesses and households.

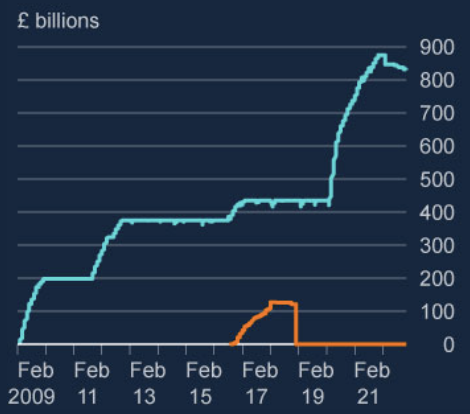

Bank of England’s cumulative bond buying has topped £800bn

As a result, the banking sector is incentivised to boost lending, giving businesses more opportunities to expand and households more avenues to spend. Rates are lower, so people should be more comfortable taking on debt.

The sum total of this complicated process is that, in theory, it boosts spending in an economy.

This massive bond buying regime has been a fixture of the global economy since 2008. This has now changed drastically, sparked by a severe inflation problem.

Inflation took off due to a combination of supply failing to respond quick enough to a sudden burst in demand after pandemic restrictions were lifted. It was turbocharged by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine roiling international commodity and energy markets.

Now most of them are selling bonds into the market – known as quantitative tightening – spearheaded by the Bank of England.

That, combined with investors demanding a higher rate of return, has pushed down prices and sent yields higher.

You might be thinking: this is all academic isn’t it?

Yields on 10-year gilt have risen sharply of late

Well that dynamic has hit the UK’s public finances. The Treasury pays for any losses the Bank accrues on QE bonds. It should be said that the Bank was sending profits to the Treasury when rates were low.

The Treasury in January paid the Bank over £4bn to cover losses accrued on its bond purchases, a trend that will continue throughout the year as the Bank shrinks its balance sheet.

Banks’ reserves held at Threadneedle Street receive interest equivalent to the UK’s base rate, which is now four per cent. Yields on the Bank’s bond portfolio is lower than that, again, prompting the Treasury to cover the spread.

That dynamic has left “the British state with a large risk exposure to rising interest rates,” Paul Tucker, a former deputy governor at the Bank, said in a report published by the Institute for Fiscal Studies late last year.

He urged Chancellor Jeremy Hunt and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to examine whether paying interest on a fraction of lenders’ reserves would limit the public finances’ exposure to losses accrued on the QE scheme.

Doing so could save the UK “£37 billion over the next few years” on its debt interest bill, he reckons.

However, a tiered reserve remuneration system would suck income out of the banking sector. A tax rise in all but name.

After over a decade of cheap money flooding into the world’s biggest economies was slayed by the historic inflation surge, trade offs on how best to wind down money printing schemes are going to have to be confronted.

As Tucker rightly acknowledges: “As of now, however, there are no easy options.”

WHAT I’M READING

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and, well, the whole government is “unwilling to admit [a growth] problem even exists”. That’s according to former rate setter Michael Saunders, who in a note for his new employers, Oxford Economics, set out his blueprint for lifting the UK economy out of its low growth malaise. Encouraging young people to study science, maths and other STEM subjects; using the state’s balance sheet to absorb eye watering childcare costs and raising public investment were all tabled as ideas by the former Bank of England man.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Yet more upbeat data on the UK economy. Consumer confidence climbed seven points in February, a much punchier increase than analysts expected. However at minus 38 points the level is still low by historical standards.