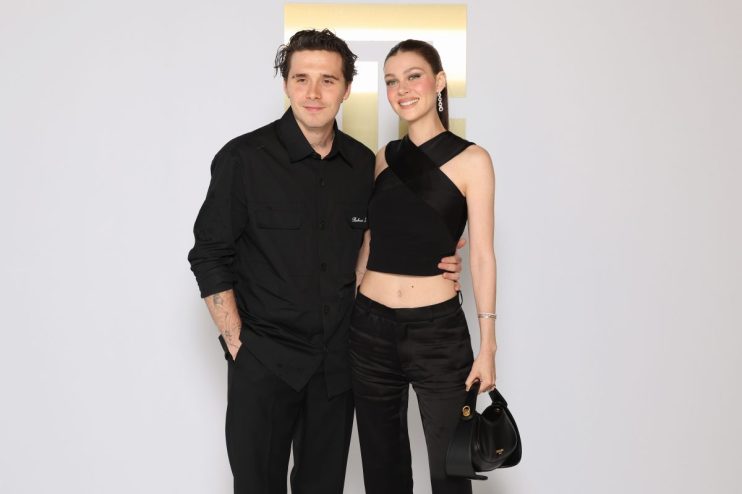

Brooklyn Beckham and why rich parents should help write their kids’ pre-nups

The fall-out from Brooklyn Beckham’s wedding will feel familiar to many wealthy parents, says Richard Hogwood

The recent discussion surrounding Brooklyn Beckham’s marriage and parental influence and involvement in the lead up to (and at) the wedding is an issue that will feel familiar to many advisors working alongside wealthy families. Where wealth is connected to a particular name or brand, or built up over a number of generations, a child’s marriage often gives rise to considerations that extend well beyond the usual party planning.

For many high-net worth families, when a child’s wedding is approaching, the legal consequences of that marriage come into sharper focus. This is the moment at which the concept of “risk” becomes tangible. In England and Wales, marriage creates enforceable financial consequences between spouses – something which is not the case when parties are simply living together. Where assets are potentially tied up in brands, businesses, trusts or long-standing investment structures, that ‘wedding’ shift can feel significant and often prompts parental intervention. It is perhaps understandable that parents who have spent years building a brand or protecting wealth want to ensure it remains secure for the future. Often, this instinct is not about trying to influence the relationship itself, but about long-term planning. What is ‘right’ for the overall family can feel in conflict with what is ‘right’ for the couple.

Increasingly, pre-nuptial agreements have become a key element of the wealth protection ‘toolkit’ for families who understand both the value of what they have built and the importance of a child entering into a marriage with clarity rather than uncertainty. For many wealthy families, a pre-nuptial agreement is intended to be a practical safeguard (an insurance policy, intended to avoid potentially costly, lengthy, polarising and public legal proceedings if the marriage does fail) rather than a sign of distrust. Since 2010, pre-nuptial agreements will generally be upheld where certain safeguards are met: the agreement must be entered into freely, with a full understanding of its implications, ideally supported by independent legal advice and proper financial disclosure and bringing about an outcome that is fair in the circumstances.

Those safeguards go to the heart of whether an agreement will stand up to scrutiny. It is also where family involvement, even when well-intentioned, can cause friction. Parents may have perfectly legitimate concerns about protecting a family business, an investment structure or inherited wealth intended to benefit future generations. For an incoming spouse, however, being told that certain assets are ‘off the table’ and not to be shared with them can feel hurtful. It can feel like, from the outset, the family expects the marriage to fail or does not somehow trust them and their intentions.

Questions of ownership and influence also often emerge in these negotiations. Parents may be funding a wedding, helping with a property purchase or providing broader financial support. While that generosity is usually well meant, it can blur boundaries. It creates a risk that the negotiations impact on the relationship between the family and the child as well as between the family and the new child-in-law.

Early conversations, well in advance of a wedding, tend to reduce tension and allow all parties to engage with the process properly. Open dialogue, supported by independent legal advice, gives each person the opportunity to express their priorities and understand the wider family context, dynamics and aims. It enables a ‘weaker’ financial party to be heard and helps them to be comforted and reassured that their needs on a divorce (and the needs of any children) would be met. It also avoids the complications that can arise when agreements are introduced late in the day, when emotions are heightened and deadlines loom.

Financial disclosure

Another key element is financial disclosure. In families with complex structures, this can be challenging. Trusts, shareholdings and inter-generational arrangements are not always straightforward to explain or quantify and both parents and their children may be hesitant to lay bare their private finances. While courts do not require forensic detail, they do require clarity. Clear and proportionate disclosure, often by way of a structured summary, is both legally effective and reassuring. It signals openness rather than defensiveness and helps the incoming spouse understand the financial landscape they are joining.

Where matters become more complicated, whether because of time pressure, international elements or the emotional weight of the discussions, professional support can be invaluable. Mediation or solicitor-led negotiations can help keep conversations constructive and focused. If a pre-nuptial agreement cannot be concluded properly before the wedding, a post-nuptial agreement may offer a sensible alternative once the pressure of the ‘Big Day’ has passed. Provided the same safeguards are met, the courts will treat such agreements with equal seriousness.

Ultimately, a pre-nup is an exercise in thoughtful preparation. For many families it is about keeping relationships and existing structures intact, rather than risk them being dismantled in the future. The aim is not to diminish the romance of the occasion, to detract from the relationship, or to leave the incoming spouse in some way vulnerable or ‘high and dry’ were there ever to be a divorce. Instead such an agreement is there to ensure that the legal and financial realities of marriage are approached with the same care and foresight families bring to other aspects of their planning. In my experience, when these conversations take place early and are handled openly and fairly, they often strengthen rather than strain the relationships that will shape the new family for years to come.

Richard Hogwood is partner at law firm Stewarts