British Politics: The 2014 events that will settle the next election

WE ARE in a state of unusually high political uncertainty. By this stage in the electoral cycle, one usually has a sense of who the next winner is likely to be. But this time we have a high level of unpredictability.

The 2015 election will be the first ever with the date known well in advance. It will also be the first when we have gone from coalition to a widespread expectation of another coalition afterwards. This will itself change the nature of the campaign, as people start plotting possible post-election deals. In this context, 2014 will bring two key events that will determine the next government.

The first is the Euro election in May. The EU is particularly unpopular at the moment, having lost its sense of direction while continuing to pose critical challenges for national decision-making. David Cameron has been forced to take a more active position than he likes, and Ed Miliband – by staying quiet – makes it likely these elections will be focused heavily on the contest between the Conservatives and Ukip.

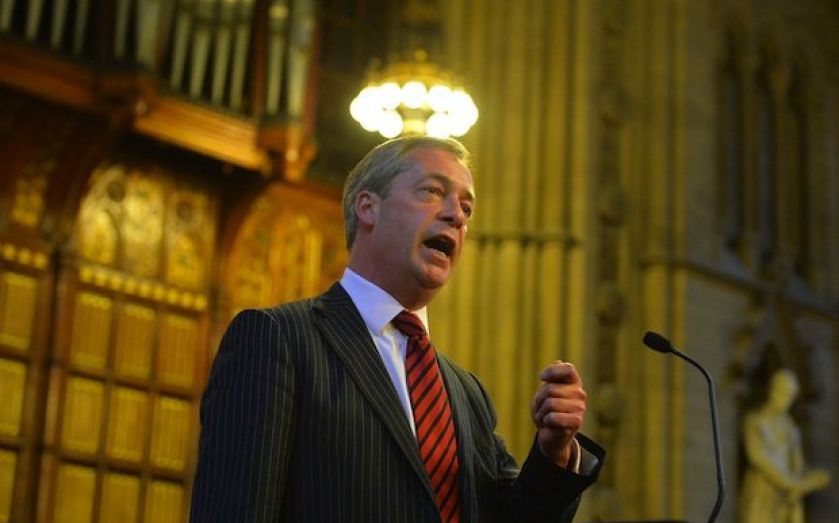

It is possible Ukip will win the Euros. Measuring their real support between elections is difficult because most people don’t think much about the smaller parties except close to the day itself, so support can fluctuate strongly as we get closer. But many Conservatives will vote for Ukip because they want to “send a message” to the Tory leadership. The trouble for Cameron is the more he responds to that pressure, the more “messages” they want to send.

Nigel Farage claims he takes votes from all parties, but the Tories suffer far more heavily than the others from his insurgency. If Ukip does get a big vote, it will create real turbulence. Not only could Tory MPs panic about the prospects of being unseated, but the odds will increase that, even if they do hold on, they will be imprisoned in another five years of a coalition they hate. A number will feel motivated to rebel, and the dynamic could get dangerous for Cameron. He may feel forced to play the EU referendum card more strongly, and risk losing the centre-ground. There are two tried-and-tested election-winning strategies: change (“kick this lot out”) and continuity (“don’t risk it now that things are going well”). The coalition, with its uncomfortable compromises, has undermined both for the Tories.

The second big electoral event is Scotland’s referendum in September. Polling suggests the vote to split from the UK will fail – the conventional wisdom is that, to radically overturn the status quo, you need powerful momentum, and that just doesn’t exist at the moment. But Alex Salmond has proved a highly effective campaigner, and the opposition to him has been weak. Many expect him to pull a rabbit out of the hat – maybe a promise of a second referendum to confirm the deal once real arrangements are in place. Unionists fear that could tip the balance. Yet even if the independence movement fails, it will have added significantly to the turbulence of the year.

Against these two events we must set the bigger picture: the economy is improving, so the Tories can claim the credit for sticking to their guns on the most important issue of all. Most people don’t like change and, in spite of some gains on the cost-of-living issue, Labour has failed to make a strong argument that they have something positive to offer. They don’t even seem minded to try. Many will therefore see a coalition of some kind as a safe way of the future, and my guess is there will be no big shifts in voting patterns: we will continue to see the polls indicating that no party will win a working majority.

Stephan Shakespeare is co-founder and chief executive of YouGov.