Billy cycling

In May last year, Abdelkhalak Lahyani, a married man of 47, was knocked from his bike as he cycled to work at the Oxo Tower restaurant. He was pronounced dead at the scene, his killer a lorry.

At the time, Leon Daniels, Transport for London (TfL) managing director of surface transport, said TfL was consulting regarding plans to redevelop the roundabout. "We know HGVs are a disproportionate cause of death and serious injury and are taking a number of steps to tackle this,” he said.

How many people are getting injured?

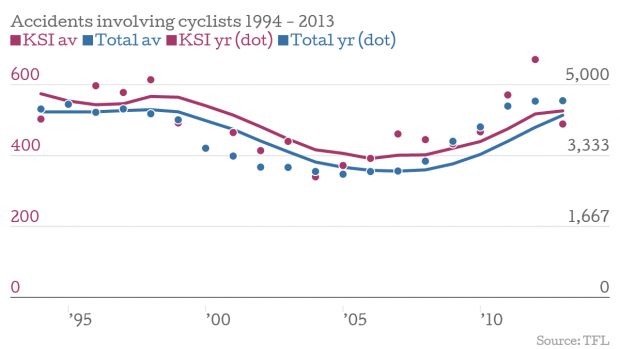

The first glance may be misleading. Since 1994 the number of daily journeys taken on a bike (to and from work would equal two journeys) has increased from 270,000 to 580,000. With the number of bike journeys increasing the number of serious accidents has fluctuated; first falling and now seemingly rising again. But even as the number of injuries seems to rise, it is not increasing the number of injuries at the same rate, or to say that the two are definitively linked. Correlation is not causality, after all.

The graph below shows a three-year rolling average of the number of people killed or seriously injured, against the number of car and bike journeys taken each day.

The ratio of bike journeys to accidents has dropped, as has the number of car journeys: the problem is that more people on the streets means more accidents, even if the risk to the individual may have fallen.

With the government trying to increase the number of cyclists on the roads, the problem could well rise. After all, the problem isn't the number of dead per 100,000 journeys, it's that the number of people dying needs to come down.

In 2013, on average, there were 12.7 accidents involving cyclists every day, against 580,000 journeys. That means you would have to cycle to work and back every day of the year, including Christmas, weekends and bank holidays for 62 years before you had an accident. For many cyclists, myself included, this doesn't hold true: reported accidents are likely merely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to slight injuries as victims are unlikely to call the police.

I remember the fear as I realised what he was doing and that I couldn't get any closer to the parked cars without hitting one. That feeling of danger happens at least once a ride, especially at busy times when drivers and riders are more impatient.

Cyclists who have ridden on the other side of the channel, in Spain, France, Portugal, and Belgium, often say they feel drivers there give cyclists more room, even in big cities. Several times, tackling Spanish climbs with friends, I've had people wave and shout encouragement "sois grandes". On a climb in Kent I dived into a hedge because I wasn't sure the combine harvester bearing down on me was going to get his angles right. We don't like cyclists here and sometimes with good reason: lycra lout isn't always a misplaced insult.

Rush hour dangers

Rush hour is the most dangerous time to be on the road. Tempers fray and people are desperate to get home. The statistics overall say each journey is less likely to result in injury as car journeys decrease, but the target must be for fewer deaths. There are more cyclists on the road than ever.

According to TFL, cyclists now account for a quarter of the traffic during the rush hour, including 36 per cent of traffic at the Elephant and Castle north roundabout, that notorious black spot. Unsurprisingly, the likelihood of any kind of traffic accident is at its highest during rush hour.

Volume of traffic is a huge contributing factor, but not the only one. Severity of injury often varies substantially depending on the other vehicle involved in the accident.

The danger of frieght

If cyclists make up a quarter of the morning rush, frieght, and the big vehicles it hauls with it, make up 28 per cent. These vehicles are of particular danger to cyclists due to impared visibility for the drivers and the huge weight of the trucks. TFL is moving towards a solution, it says, which would include retiming deliveries to reduce congestion and improve efficiency, as well as helping with cycling safety. Freight operators and TFL have been trialling elements of the scheme, including Changing loading only restrictions from 10:00–16:00 to 19:00–23:00.

Of the largest vehicles listed in TFL’s data, the => 7.5 tonne category, there were only 47 accidents, yet over 20 per cent of those resulted in death or serious injury. 28 per cent (4 of 14) of all fatalities came from this class of vehicle. The high proportion of serious injuries in the "other" vehicle type can be explained by some of the vehicles in that category. According to the Metropolitan police, examples include

Ambulances, fire engines, motor caravans, electric scooters (powerchairs) and motorised wheel chairs, quad bikes, motorised scooters, pedestrian controlled vehicles with a motor, refuse vehicles, road rollers, mobile cranes, tower wagons and army tanks.

The map below shows collisions by vehicle type. Use the buttons to add and remove vehicle categories. The larger the dot, the more serious the injury.

Towards a solution

Andy Cawdell co-founder of the London Cycling Campaign (LCC), thinks that one of London’s major problems is its antiquated transport system and the grinding gyratories that lead cyclists to clash with traffic.

A look at the map above appears to support Cawdell's conclusions; the Elephant and Castle north roundabout has a spattering of dots. In 2011-2013 there were 51 collisions reported there: 44 slight and seven serious. TFL is planning to redevelop the roundabout at a cost of £20m, transforming it thus:

The scheme, says TFL, was popular with residents, garnering 80 per cent support. Cawdell doesn’t believe this goes far enough. He says that the roundabout is especially vulnerable to what cyclists know as the left hook; when a vehicle turning left collides with a cyclist continuing straight. The road at the roundabout itself is wider than its tributaries, meaning that cars accelerate when entering the roundabout and traffic is forced together when leaving it.

The solution, Cawdell believes is to be more radical. The roundabout, and others, need a system where traffic is filtered by direction. This would eliminate left hooks and make cyclists and traffic far more predicable. In addition, traffic should be segregated, with cyclists kept as far from motor vehicles as possible. Thirdly, it says, cyclists would be safer kept next to the kerb as often as possible; not meandering with intent through streams of cars.

The LCC has other ideas, too. TFL has organised cycle routes that avoid the roundabout, but they are slow and inconvenient, attracting what the LCC says is a mere 10 per cent of cyclists. At Elephant and castle it proposes a redirection, improving the efficiency of the route to increase the number of cyclists using it.

The problem is a complex one: how do you reinvent a city that has been built and rebuilt without cyclists in mind? On the one hand, the data shows something is working. You are now less likely to become a recorded statistic than you were in the past. But as the government encourages more and more people to take to their bikes, the total number of casualties is stubborn. Fourteen dead cyclists is always too many, especially with so many serious incidents centred around the same danger points.