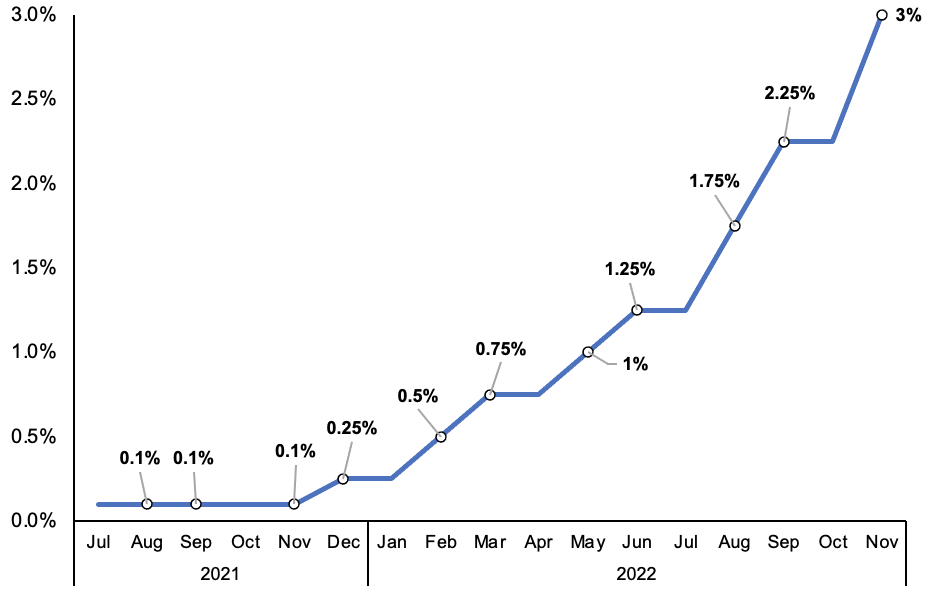

Bank of England delivers largest rate hike since 1989 and signals more to come

The Bank of England today hiked interest rates by the largest amount since 1989 and signalled more rises are coming.

The Bank’s rate setting committee voted unanimously to lift borrowing costs 75 basis points to three per cent, the highest level since 2008 and the eighth rise in a row.

The pound shed more than 1.5 per cent against the US dollar on the news, while the FTSE 100 fell 0.5 per cent.

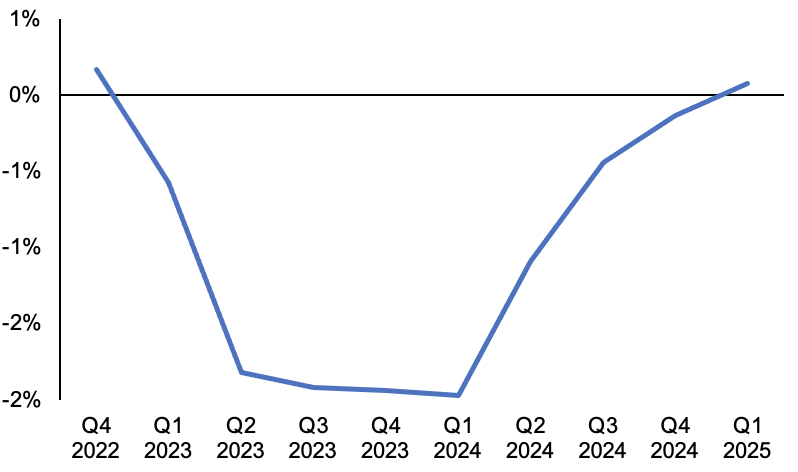

UK households and businesses are set to shoulder the longest recession since comparable records began at eight quarters.

The slump will last until the end of 2024 and is likely to be the longest recession since the 1920s, officials forecast.

Consumers are likely to respond to soaring mortgage rates, eye watering energy bills and a higher cost of living by cutting spending, plunging the economy into the record contraction.

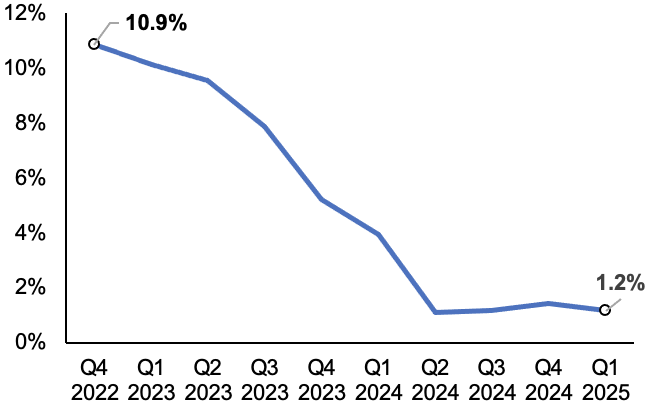

Despite the warning, the Bank will have to pile even more pressure on to Brits to stop inflation rising beyond a peak of 10.9 per cent.

Interest rates have climbed eight times in a row

Governor Andrew Bailey said borrowing costs “may have to go up further” but to “less than currently priced into financial markets”.

His comments illustrate the Bank is now trying to rein in market expectations, something rate setters typically avoid.

The Bank’s bleak forecast is based on interest rates hitting market expectations from mid-October of around 5.2 per cent, which the Bank has previously indicated it is unprepared to do. Rate bets have since fallen to around 4.75 per cent.

In fact, if they stay at three per cent, the current level, inflation falls below the Bank’s two per cent target over the long run.

But, if borrowing costs follow the market path, the economy will shrink just under three per cent over the course of the entire slump.

Just a couple months ago, Bank officials said the recession would be mainly driven by elevated energy bills and would last 15 months.

However, higher mortgage rates are now set to play a big part in steering the slump. Rates have topped six per cent, mainly caused by banks passing on a bond yield surge in the immediate aftermath of former prime minister Liz Truss’s mini-budget.

Bank of England’s GDP projections are bleak

Markets were betting the Bank could lift rates as much as 125 basis points today and send them to a peak of more than six per cent in the days after Truss’s disastrous fiscal statement.

Investors have since been calmed by prime minister Rishi Sunak and chancellor Jeremy Hunt scrapping nearly everything in that package, causing mortgage rates to edge lower.

A 75 basis point hike today was in line with current market expectations.

The Bank’s forecasts were produced without accounting for Sunak and Hunt’s budget on 17 November.

The pair are expected to jack up taxes and slash spending to fill a £50bn hole in the public finances, meaning the length and severity of the recession could be worse than the Bank expects.

“The most important thing the British government can do right now is to restore stability [and] sort out our public finances,” Hunt said.

“There is potential that” tougher government and monetary policy could “actually exacerbate the economic situation,” Martin Beck, chief economic adviser to the EY Item Club, said.

Analysts also said the government’s stricter stance could shoulder some of the inflation fighting burden, meaning the Bank is unlikely to raise rates above four per cent and may even start cutting them sooner to revive the economy.

“The threat of a substantial tightening of the fiscal stance means the risks are now skewed towards a lower peak in Bank Rate and towards subsequent rate cuts starting sooner,” Andrew Goodwin, chief UK economist at Oxford Economics, said.

Inflation is expected to fall below the Bank’s target

Seven members, including governor Andrew Bailey, of the nine strong monetary policy committee (MPC) backed kicking rates 75 basis points higher.

One, Swati Dhingra, favoured a 50 basis point rise, which the Bank had done twice in a row in August and September.

Another, Silvana Tenreyro, wanted a small 25 basis point rise.

Inflation has climbed to a 40-year high 10.1 per cent, more than five times the Bank’s two per cent target, forcing it to hoist borrowing costs from a record low 0.1 per cent.