Anxious East Africa holds its breath: Still no election winner while fraud claims start to fly

NAIROBI – East Africa is holding its breath this Friday morning as Tuesday’s cliffhanger elections in regional powerhouse Kenya still has not produced a clear presidential winner.

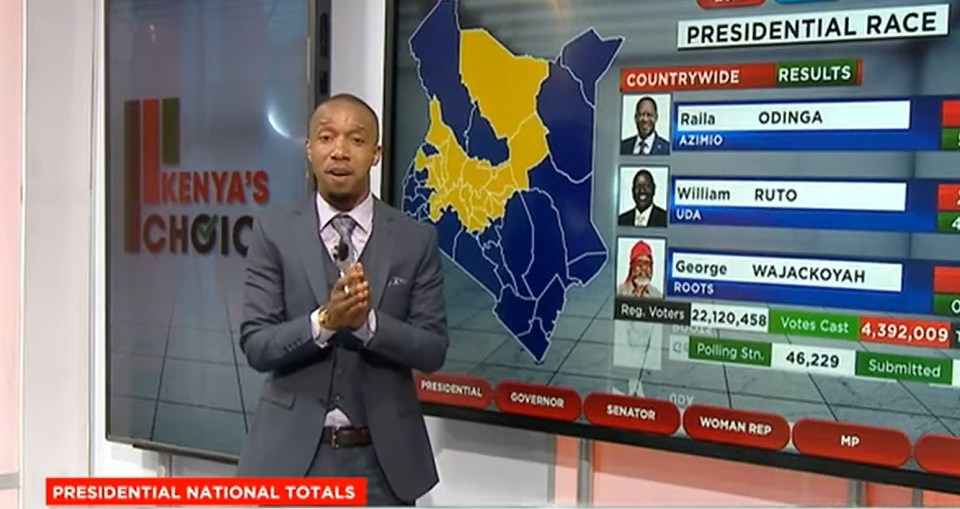

While vote counting in the country is reaching its final stages, in an extremely close race between the two main candidates, confusion is growing as a range of national and regional TV stations and newspapers report different results.

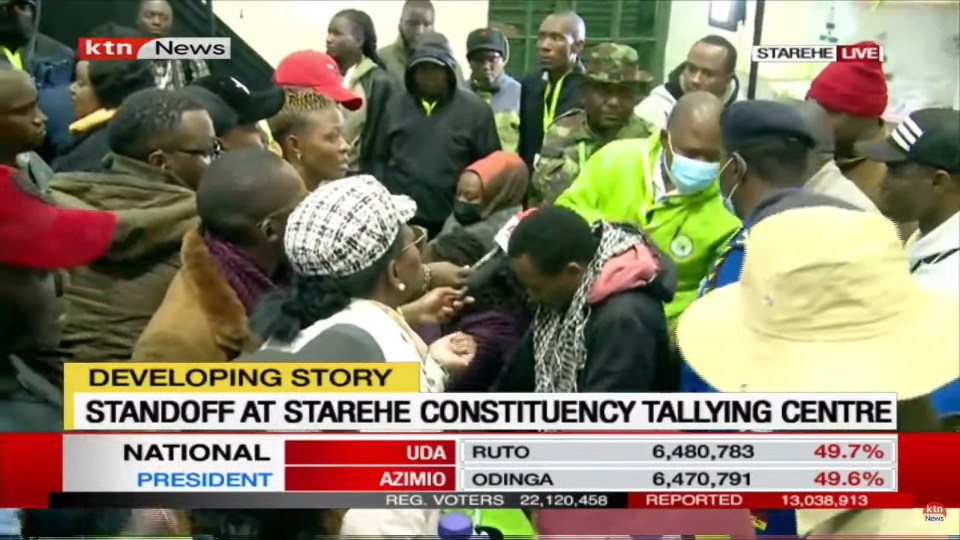

Moreover, several standoffs and scuffles have broken out across the country, primarily at polling stations and mostly disputes over vote counting and submitted or incomplete ballot papers.

‘Hustler’ taking a slight lead

Since Tuesday evening an extremely close race has unfolded between the two main candidates for the presidency, with millions of Kenyans holding their breath as they wait what Friday will bring.

Opposition leader Raila Odinga, who is backed by the outgoing president and seen as the establishment candidate, faces deputy president William Ruto, who styles himself as an outsider and a “hustler”.

Both Odinga and Ruto are polling close to 50 per cent of the vote, but according to most media, the ‘hustler’ is taking a slight lead at 49.91 per cent of the vote, versus Odinga at 49.41 per cent, as of 8 a.m. UK time on Friday morning (10 a.m. local time).

Others, such as the TV network KTN put Ruto at a lead of 49.7 per cent, versus Odinga at 49.6 per cent.

By law, results must be announced within one week, so before this coming Tuesday.

Either Odinga or Ruto will replace outgoing President Jomo Kenyatta leaving government after a decade at the helm.

More than 22m registered voters had the chance to endorse their favourite candidates in 46,232 polling stations across the country on Tuesday.

However, fewer Kenyans voted. Turnout was just under 60 per cent as polls closed with some voters citing little hope of real change.

Eerily quiet

Since Tuesday’s elections many Kenyan streets are deserted, as millions of people nervously wait at home what the results will bring.

Apart from chaotic scenes at polling stations, most streets are eerily quiet, and there is less traffic than normal.

Public transport is also at a minimum and in capital Nairobi a large police presence can be spotted on the street.

Nevertheless, Tuesday’s election was considered close but calm.

This is partly because economic issues such as widespread corruption and rising cost of living were of greater importance than the ethnic tensions that have marked past votes with sometimes deadly results.

Regional powerhouse

Kenya is a standout with its relatively democratic system in a region where some leaders are notorious for clinging to power for decades.

Its stability is crucial for foreign investors, the most humble of street vendors and troubled neighbours like Ethiopia and Somalia.

2007 election violence

Elections can be exceptionally troubled, as in 2007 when the country exploded after Mr Odinga claimed the vote had been stolen from him and more than 1,000 people were killed.

Mr Ruto was indicted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity for his role in the violence, but his case was terminated amid allegations of witness tampering.

In 2017, the high court overturned the election results, a first in Africa, after Mr Odinga challenged them over irregularities.

He boycotted the new vote and proclaimed himself the “people’s president”, bringing allegations of treason. A public handshake between him and Mr Kenyatta calmed the crisis.

This is likely Odinga’s last try. Mr Ruto and Mr Odinga have said they will accept the official results — if the vote is free and fair.

“It is every Kenyan’s hope,” the president told journalists on Tuesday.

Rising food prices

Rising food and fuel prices, debt at 67 per cent of GDP, youth unemployment at 40 per cent and corruption put economic issues at the centre of an election in which unregulated campaign spending highlighted the country’s inequality.

“We need mature people to lead, not someone who abuses people. Someone who respects elders,” said 55-year-old teacher Rosemary Mulima.

She still has “very high” hopes for Mr Odinga on his fifth try.

The top candidates are Raila Odinga, a democracy campaigner who has vied for the presidency for a quarter-century, and 55-year-old Deputy President William Ruto, who has stressed his journey from a humble childhood to appeal to struggling Kenyans long accustomed to political dynasties.

“In moments like this is when the mighty and the powerful come to the realisation that it is the simple and the ordinary that eventually make the choice,” Mr Ruto told journalists on Tuesday evening.

“I look forward to our victorious day.”

Raila Odinga last night

He urged Kenyans to be peaceful and respect others’ choices.

“I have confidence that the people of Kenya are going to speak loudly in favour of democratic change,” Mr Odinga told journalists on Tuesday evening. A cheering crowd jogged alongside his convoy as he arrived to vote in Nairobi.

To win outright, a candidate needs more than half of all votes and at least 25 per cent of the votes in more than half of Kenya’s 47 counties. No outright winner means a run-off election within 30 days.

Results must be announced within a week, but impatience is expected if they do not come before this weekend.

“What we want to try to avoid is a long period of anxiety, of suspense,” said Bruce Golding, who leads the Commonwealth election observer group.

Outgoing President Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Kenya’s first president, cut across the usual ethnic lines and angered Mr Ruto by backing long-time rival Mr Odinga after their bitter 2017 election contest.

But both Mr Odinga and Mr Ruto have chosen running mates from the country’s largest ethnic group, the Kikuyu.

Mr Odinga, 77, made history by choosing running mate Martha Karua, a former justice minister and the first woman to be a leading contender for the deputy presidency.

The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission estimated that final turnout would be above 60 per cent, far lower than the 80 per cent in the 2017 election. That would make it Kenya’s lowest turnout in 15 or even 20 years.

The electoral commission signed up less than half of the new voters it had hoped for, just 2.5m

“The problems from (the previous election), the economy, the day-to-day life, are still here,” said 38-year-old shopkeeper Adrian Kibera.

“We don’t have good choices,” he sighed, calling Mr Odinga too old and Mr Ruto too inexperienced.