Antony Gormley at the Royal Academy: An existential crisis has never felt so invigorating

This giant Antony Gormley retrospective feels like the artist’s unified theory of everything. The works are drawn from four decades of output, but feel so indelibly fused with the famous halls of the Royal Academy you can barely imagine them elsewhere.

Gormley bends and shapes the gallery to his will like a potter at a wheel; you worry that it might never be the same again. One room has been torn apart by monstrous cubes that seem to make the walls bulge; a ceiling looks ready to collapse under the tremendous weight of the art; one gallery is flooded.

A recurring theme is the impossible weight of existence, often expressed through a literal impossible weight. Apples bigger than cars hang inches from the ground, pregnant with the expectation of an impact that never comes. One room has tonnes of metal mesh dangling from the ceiling like the skeleton of a bombed-out building. Standing beneath it you can feel the awful power of gravity bearing down on you, unseen but tangible, held back by nothing but a few slender cables.

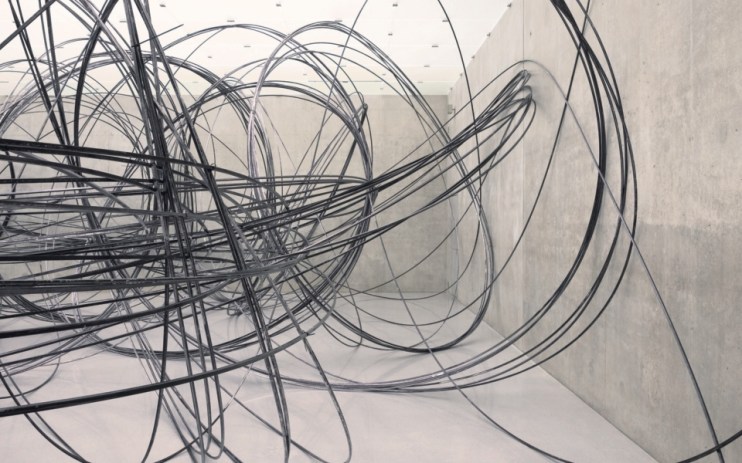

Gormley plays with three dimensions the way a graphic designer manipulates a flat surface, relishing the power of a single unbroken line. A series of cables whoosh around the gallery. One room contains just three bisecting metal lines (a real palate cleanser after the chaotic minutiae of the Summer Exhibition) – another is filled an angry scribble of coiled wire, like someone desperately trying to get their biro to work. You have to stoop to make your way through it, and on the far side, isolated in a room on its own, stands a single figure built from blocks.

The artist has lost none of his fascination with the human form. The first room features piles of blocks that take human form after you stare at them for a while; a jagged heap becomes elbows and knees and noses. Later there are jumbled pieces of clay that look like dismembered bodies placed clumsily back together.

Then there are those famous nude self-portraits that gaze dolefully out to sea at Crosby beach. Here they’re clustered together in a single room, jutting unnaturally from the walls, hanging from the ceiling, the same penis repeated a dozen times, defying gravity. Gormley seems desperate to find some essence of what it is to be human, some shared property that might make sense of it all.

If this sounds a bit maudlin, it’s really not. Gormley knows how to play to the crowd. One piece has you crawling through metal blocks that make up the insides of a giant, fumbling your way through the dark, searching for the light. An existential crisis has never felt so invigorating.

• Antony Gormley at the Royal Academy is supported by BNP Paribas