Why the Bank of England and Fed could welcome Credit Suisse and Silicon Valley Bank failures

There’s been reams and reams of wild predictions about whether we’re slipping into another financial crisis, triggered by the collapse of US tech lender Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Credit Suisse’s arranged marriage with its crosstown rival UBS.

Blackrock chief Larry Fink even warned in his annual letter to shareholders we’re slipping into a slow burning financial meltdown. Crikey.

It’s tough to know what happens next. When Lehman Brothers failed, there was a couple weeks of calm in markets. Then everything exploded.

Last week, European banks clawed back some of their losses, then tumbled again. Debt markets were choppy. US regional banks sank. The tea leaves are sending mixed messages.

Now, the underlying dynamics that led to SVB and Credit Suisse’s failures are different from those that took down Lehman.

SVB did what every bank does: borrowed short and lent long, but on a herculean scale. By piling cash into US government debt, it exposed itself to what financial gurus call “duration risk”.

Once customers came knocking for their cash, the assets SVB held to meet those demands couldn’t be sold off quickly enough and even if they were, their price had plummeted. Its demise had nothing to do with the credit worthiness of its customers. Poor risk management was the poison.

Credit Suisse was the victim of a confidence spiral. It’s looked shaky for years and was the obvious target for investors to punish.

So, crisis or one-offs? Examining the profile of the banking sector as a whole indicates the risk of another financial meltdown is slim.

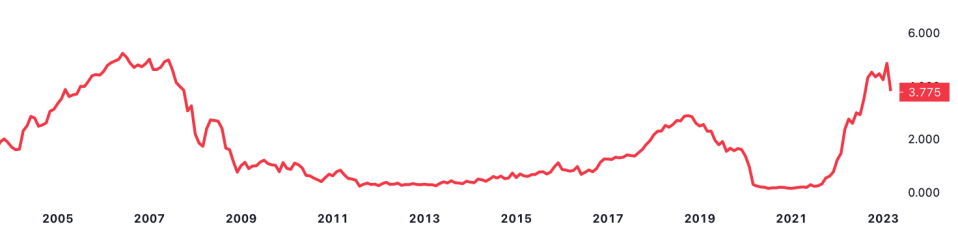

Banks are harbouring unrealised losses…

Rules put in place after 2008 have tightened lending standards.

That has pushed down the share of people who would struggle to repay their debts if rates rose suddenly – the “subprime” mortgagors of 2008 – sharply lower.

A big chunk of homeowners in the UK, US and Europe will need to remortgage this year on much higher rates. If the regulatory regime of the last decade or so has worked, then defaults should be limited.

Families now are also much less indebted than they were before 2008, so they have greater capacity to absorb higher mortgage bills.

But that event illustrates banks have capital readily available to sacrifice if losses emerge.

Let’s park the plumbing of banks and financial markets and focus on what’s coming down the pipeline.

Lots of people are still confused as to why the financial crisis sparked such a long drawn out recession that the global economy is still recovering from now.

Ignore stock markets tumbling. They, in the main, have little impact on the real economy. The issue that choked growth was the credit crunch that came after the high-profile bank collapses.

Banks stopped lending to each other. Money dried up. Families and businesses couldn’t get ahold of capital. Economic activity stalled for years.

That dynamic could unfold in the coming months.

Right now, banking executives will be worried about one thing: being hit by people suddenly pulling their cash.

To prevent being caught with their pants down in such a scenario, they will be drawing up plans to tighten lending standards to retain money within the organisation.

… caused by a surge in government debt yields

Just like SVB, many lenders are probably concerned about not being able to raise enough cash to cover the demands, strengthening incentives to hunker down.

This makes sense, from their point of view.

If every bank does that, then economies are in for a bumpy ride.

Businesses that would hire an additional person won’t be able to source the money to do so. Young families with good credit profiles and high deposits won’t be able to buy a house.

Scarce credit supply is one of the main factors that tips economies into recession. It is also one of the toughest problems to fix.

There is a silver lining hidden within this scenario (should it play out). Private sector banks would do some of the heavy lifting for the likes of the Federal Reserve, Bank of England and European Central Bank by chilling economic activity.

Fed chair Jerome Powell acknowledged that point in his post rate decision press conference last week.

It’s worth remembering what central banks are trying to do: sledgehammer households and firms with higher interest rates to tackle inflation.

If household name banks do that for them, then maybe, just maybe, Powell and his counterparts could park some of the blame for the coming economic hardship with somebody else.

WHAT I’M READING

The Bank of England is done with raising interest rates, pretty much every economist in the City now reckons after last Thursday’s eleventh rise in a row to 4.25 per cent. Everyone except Barclays. They bumped their peak rate forecast higher to 4.5 per cent, mainly because underlying inflation is still pretty high.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s widening of childcare support at the budget earlier this month was roundly welcomed. It will help a lot of people with what have been steeply rising nursery bills. But there’s a catch. Earn a £1 over £99,999 and you’re cut off from government help. The Centre for Business and Economic Research reckons 55,000 will be caught in that net.