Vampire films never get old… or do they?

FILM

ONLY LOVERS LEFT ALIVE

Cert 15 | By Steve Dinneen

Three Stars

ONLY Lovers Left Alive is a movie with vampires in it, but it’s not really a vampire movie. It hemorrhages introspection and indie sensibility rather than horror panache. There’s hardly any blood in it. If I were the kind of writer who used bad puns, I might say it lacks bite. But it doesn’t suck.

The action – and I use the word in the loosest possible sense – is split between Tangier, home of Tilda Swinton’s bohemian intellectual Eve, and the abandoned, decaying ghost-town of Detroit, where Tom Hiddleston’s jaded rocker Adam resides.

They are members of an undead elite, which has wielded a silent influence over the greatest artistic and scientific achievements of the last millenia. Adam once penned an adagio for Schubert and the curmudgeonly old Christopher Marlowe, another member of their coven, is still hacked off at Shakespeare for getting the credit for his work. They used to hang out with Byron, but he was a nasty piece of work. These days Adam lives in a crumbling tenement building, recording rock ‘n’ roll funeral dirges, with only his back-combed hair for company. He’s in bad shape – ready to give up the ghost, or at least the vampire. Thankfully his very, very old flame Eve picks up on his existential angst during a Skype chat and hops on the first night-flight Stateside.

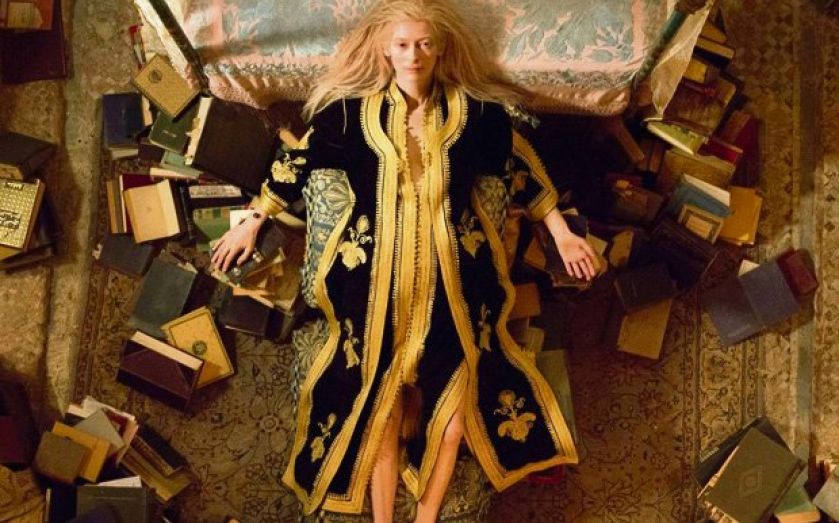

If it sounds a tad pretentious, that’s because it is, but it’s also very pretty. Director Jim Jarmusch paints with a murky palette of grey, umber and burgundy – both the rotting post-industrial cityscapes and claustrophobic Moroccan alleys have a wistful, vacant beauty. The aesthetic is unabashedly neo-gothic, with the undead characters displaying a stereotypical predilection for vintage robes and gilded hardback novels.

Thematically, Only Lovers offers nothing groundbreaking – the vampire-as-rockstar was imagined by Anne Rice in 1976’s Interview with the Vampire, and the idea of a global sect of artists and scientists communing echelons above the hoi polloi is a furrow well ploughed in Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. The often-drawn parallel between vampires and drug addicts isn’t exactly new, either; Jarmusch underlines it a few times for good measure, with the act of drinking blood – out of gothic goblets, of course – soliciting dilated pupils, rolled-back eyes and moans of heroin-esque ecstasy. Even the sourcing of good, clean “O-negative” from hospital blood banks (“we can hardly throw them in the Thames with the tuberculosis floaters these days, can we?”) has been done before.

But rather than collapse into self-parody, the adherence to clearly signposted vampire motifs allows Jarmusch to focus on grander ideas. The languid approach that’s characterised his filmmaking career – from Broken Flowers to Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai to the taciturn Coffee and Cigarettes – puts the dialogue front and centre, and the blood-sucking element becomes a vehicle to explore the futility of life and the alienation that comes with age.

Swinton is astutely cast – her ethereal looks and mantis-like frame make her a fine vampire, and Hiddleston’s intelligent eyes and thespy delivery are perfect for the detached, maudlin Adam. Together they provide enough chemistry to pull you through the film’s more self-indulgent moments. Only the normally-excellent Mia Wasikowska disappoints, with a rather hackneyed take on the spoiled, sybaritic younger sibling.

Occasionally Jarmusch spreads it on a bit thick – the fetishisation of analogue technology, for example, brought to mind the vomitorious scene from Seeking a Friend For the End of the World in which Keira Knightley riffs about her parents’ vintage record player. But there’s a knowingness with Only Lovers, a sense that we’re all in on the joke, usually signified by Hiddleston’s slightly arched eyebrow.

Like most of Jarmusch’s work, his latest film will polarise opinion. It’s slow and often navel gazing. It is weighed down by a sense of its own importance, but a wicked sense of humour simmers beneath the surface. It’s unlikely to win Jarmusch many new fans but those who appreciate his lethargic pacing and pensive disposition will find a lot to like here.

FILM

STALINGRAD

Cert 15 | By Melissa York

Four Stars

HOW do you immerse an audience in the horror of one of the bloodiest battles of human history? No amount of techno wizardry can accurately replicate the experience but filming it in 3D for IMAX is probably a good start.

Stalingrad, Russia’s entry for the Best Foreign Film category at the Oscars, is the first non-American film to be released for the giant screen (unless you believe, as BAFTA does, that Gravity is British). The result is an epic spectacle where the sound of every gunshot rattles through you and every bomb-blast makes you jump. Its a bleak world, coated in a thick layer of ash that lingers in front of your eyes. One million men died in the battle for Stalingrad, which was arguably the turning point of the Second World War. Surprisingly, the film doesn’t dwell on battle scenes, choosing instead to occupy itself with human relationships that are destroyed by war and, in turn, destroy a soldier’s desire to fight.

Soldiers are shown shooting civilians indiscriminately in the street – or even burning them as a sacrifice before battle – while those who stop to form relationships are seen as weak. The Russian soldiers say they don’t “need” civilians around because their presence is a distraction from the emotional disconnect they need in battle. Similarly, as soon as Nazi officer Peter Kahn falls in love with a Russian woman, he loses his focus on the battle and is never able to regain it, much to the disgust of his commanding officer.

While IMAX has already offered us a glimpse of the future with films like Prometheus, Stalingrad proves that it can also be a breathtaking way to relive the past.

THEATRE

1984

Almeida Theatre | By Steve Dinneen

Four Stars

George Orwell, or at least his seminal novel 1984, is referenced so often in popular culture that it’s collapsed into cliche. So how do you adapt it for the stage without giving your audience the feeling they’ve seen it all before? Creators Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan’s solution is to recreate protagonist Winston Smith’s paranoia, his creeping feelings of insecurity and isolation, and to put the audience in his place, rather than to simply retell his story. It opens with Winston sitting around a table with an group of unfamiliar people who seem to talk through him. He may be there with them, or it might be a memory. Or it might be something altogether more sinister.

Icke capitalises on the fact that most of his audience will be aware of the novel’s key concepts, and there’s a nagging doubt running through the first act that Winston may already be trapped in the infamous Room 101 (a torture chamber where a person’s worst fears are realised). As the play gathers pace, scenes begin repeat themselves, with ever bigger cracks appearing in both the narrative and the set itself. The lights cut out, actors freeze, disappear and swap places. Piercing blasts of static cause your ears genuine pain. Parts of the action are filmed live from off-stage and beamed onto a projector, putting the audience in the place of the novel’s voyeurs screaming at the Daily Hate. And Big Brother is always watching – peering from behind the set or flashing up on a giant screen.

One of the big reveals is impeccably staged – I won’t give any more away – and the torture scenes border on the gratuitous. It’s brash, bravado theatre, and it certainly never feels old.