The Interview: A hacker vigilante who could break the Internet

Elena Siniscalco interviews Chris Wysopal, a friendly neighbourhood hacker who also happened to crack into Microsoft back in the ’90s

Chris Wysopal smiles warmly and speaks fast. You could easily mistake him for a friendly, slightly nerdy dad. You certainly wouldn’t think he was one of the most famous hackers of the ‘90s. You wouldn’t imagine he stood up in front of the US Senate and said he could shut down the Internet in 30 minutes.

Wysopal grew up in bustling Boston, where he found food for his curious mind in the form of a rising interest in computers and hacking. A young, tech-savvy man, he started joining monthly meet-ups of the independent magazine “Hacker Quarterly”. After a year of coming to these meetings, he found his people.

Before L0pht came into formal existence, two of their number were simply looking for a space they could store their computers – and a place to meet that wasn’t the local pizza shop. This was the 90s and computers weren’t skinny, shiny things, they were great hulking pieces of technology. The end result was an odd mish-mash of milliners and hacker vigilantes.

It all started from there: young friends trying to be smarter than the big guys. Soon enough, one of them came up with the idea to hack Microsoft – then a tech behemoth with few competitors. Apple, Meta, and Google were still in their infancy.

It was almost a game: Wysopal and his friends simply wanted to see how vulnerable Microsoft was to different hacking techniques. “You could figure out ways to take over that software, compromise it, come up with these vulnerabilities and exploit it”, he says. Unlike most modern day fraudsters, they were more like cyber vigilantes, and once they got underneath the hood, they reached out to Microsoft to tell them where they were exposed.

Wysopal insists they weren’t the “bad guys” and never used the information they found for personal or commercial gain. Part of it was tech voyeurism, a mix of camaraderie and bravado. “I’ll admit it, as a young person it’s kind of fun to go against the bad guy”, he says. The L0pht used to call it “pulling their pants down”.

Thankfully, these guys who thought themselves so clever were also conscious of how serious the problem was. Wysopal was worried if he could hack into Microsoft, bad actors could as well, and believed it was the tech companies’ responsibility to develop safe software.

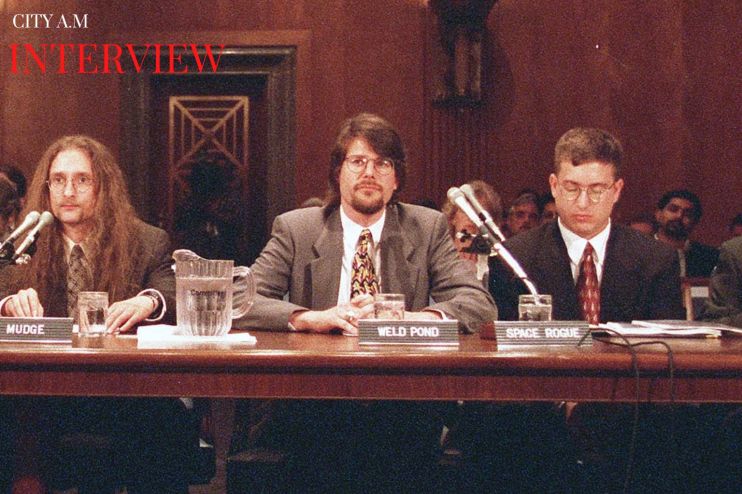

And that’s how the seven of them ended up testifying in front of the Senate 25 years ago. No hacker before had been in front of the Senate. Pictures from the time show the L0pht members in suits, sitting with their hackers’ names written on plaques in front of them. They didn’t use their real names for fear of repercussions; Wysopal was “Weld Pond”.

“They wanted to get our viewpoint, which I found was a huge turning point in how governments and businesses thought about cybersecurity”, says Wysopal. They told the Senate the only way to secure governments and companies on the Internet was to “use offensive, adversarial techniques on yourself”. In the same way car companies do dummy car crash tests, so should governments and companies attack themselves to spot their vulnerabilities. If you don’t, someone else will, the hackers told the Senate.

Fast forward 25 years, and some of this has finally made it into the mainstream. We now call it “secure by design”: it means companies aim to release software that’s been tested for its safety before it’s released, rather than after. This model is central to new laws, set to come in next year, which govern safety of all consumer products connected to the Internet – everything from your Peloton bike to your iPhone. The government hopes everything which uses an Internet connection will be “secure by design” in the next five to ten years. “I just wish it happened five or ten years ago”, says Wysopal.

He tries to be optimistic, saying we’ve learnt a lot in the past 25 years, but you can tell he doesn’t fully mean it. He has the resigned look of a Messiah who was only partially listened to.

It’s complicated: when it comes to governments, there are “haves and have-nots”. Cyber security is expensive and not every country can afford to heavily invest in it. But even within governments, most of the funding goes to protecting the military or intelligence offices. Hospitals or schools get less funding, and that’s how hackers get in: through MRI machines connected to the Internet, or through schools’ software. The infamous “WannaCry” attack on the NHS in 2017 left 50 health trusts exposed. More recently in May, two of the major hospitals in Milan were attacked and had to switch to paper-only data sharing for days.

Wysopal is not a hacker anymore; he calls himself a “vulnerability researcher” and has founded a company, Veracode, which automates what he was doing back in the ‘90s. “We make the software that tests the software that Microsoft or eBay or other companies are making”, he explains with his grown-up/good-guy hat on.

If predictions are true, some of us will have around 25 devices connected to the Internet in our homes in the next 5 years. We’ll need a lot of people like Wysopal who can guide governments and companies in the right direction. When I point that out, he smiles humbly and says the zenith of security will be reached when these people are not needed anymore.