Day two of shutdown

■ Almost 1m workers on leave as the deadlock enters a second day

■ US risks default on debts if a deal is not reached by 17 October

■ Dollar slumps but traders keep their cool to calm markets

HUGE swathes of US government services were shut down yesterday after politicians failed to agree a budget for the new financial year.

Leaders now have just over two weeks to strike a deal before the US will hit its debt ceiling, run out of cash and default on its debts – an unprecedented crisis that would send shockwaves around the global economy.

More than 800,000 federal workers running everything from national parks to food safety inspections have been sent home on unpaid leave as the state could not pay the bills for the non-essential services. The shutdown is hitting the economy to the tune of $771m (£476m) per day, according to Oxford Economics.

Despite the damage and the fear of a default, US markets edged up on the hope that several small concessions offered by Republicans yesterday were the early signs of a solution. The S&P 500 rose 0.8 per cent and the Dow Jones was up 0.4 per cent. But the dollar hit a nine-month low of $1.62 to the pound.

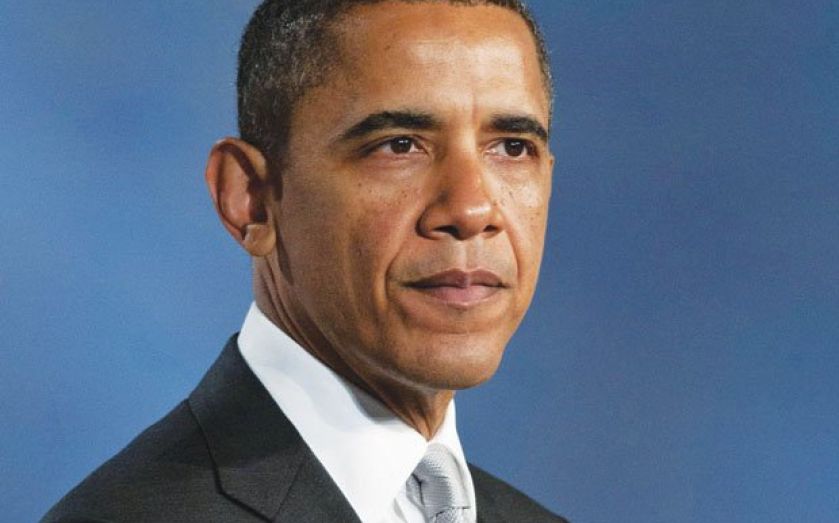

President Barack Obama stood firm in a speech yesterday, telling Republicans he will not back down on his healthcare plans, the key sticking point in budget talks.

“Congress, generally, has to stop governing by crisis. I’m not going to allow anybody to drag the good name of the United States of America just to refight a settled election or extract ideological demands,” said Obama. “If they go through with it this time, and force the United States to default for the first time in its history, it would be far more dangerous than a government shutdown. It would be an economic shutdown.”

Treasury secretary Jack Lew said last night that his department has started using “final extraordinary measures” to pay the nation’s bills, though this does not alter the 17 October date that the US is expected to reach its debt ceiling.

Credit ratings agencies said any default would automatically remove the US’s strong rating – in turn forcing huge numbers of investors to sell bonds, hitting American borrowing costs and creating a flood of cash into other assets. Firms and pension funds invest heavily in US government bonds and risk being badly burned if the state defaults.

“Investor confidence in the full faith and credit of the US would be undermined in such a scenario,” said Fitch. “This faith is a key underpinning of the US dollar’s global reserve currency status and reason why the US triple-A rating can tolerate a substantially higher level of public debt than other triple-A sovereigns.”