Screenshot: Is the Super League the biggest PR disaster of all time?

This week

**Media Moment of the Week: Radio loses a legend

**Is the Super League the biggest PR disaster of all time?

**Is Netflix’s pandemic party finally over?

Media Moment of the Week: Radio loses a legend

For many Brits, radio has been a much-needed source of entertainment (and company) during the pandemic. But long before anyone had heard the term ‘social distancing’ there’s always been one DJ in the ears of a generation of music fans.

After 17 years at BBC Radio 1, Annie Mac this week announced she will hang up the headphones for the final time in July. It’s the end of an era for British radio, but Mac is promising podcasts and more fiction following the publication of her debut novel Mother Mother next month, so watch this space…

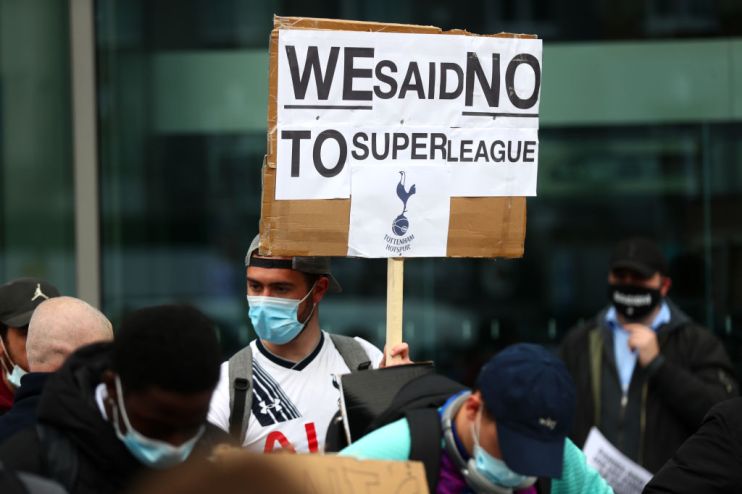

Is the Super League the biggest PR disaster of all time?

In April 1991 Gerald Ratner was flying high. The businessman had grown his family’s small retail chain into the biggest jewellery group in the world, making himself a fortune in the process. Then, for reasons known only to him, he threw it all away. In a now-infamous speech, Ratner described his products as “total crap”, adding that one set of earrings was “cheaper than an M&S prawn sandwich but probably wouldn’t last as long”. The company’s value plunged by £500m and Ratner was swiftly ousted. It’s often cited as the biggest PR disaster of all time, but fast forward 30 years and we have a new contender: the calamity that was the European Super League.

As the dust settles on the ruins of the ESL — a project so toxic that it healed British divisions better than clapping on doorsteps ever could — another question emerges. How could a group of football clubs so flush with cash make such a mess of the launch?

At the heart of the problem was a complete lack of consultation with fans (or even players and managers), something PR consultant Andy Turner describes as fundamental to any kind of strategy change. “They either have zero idea what they’re doing or were just so arrogant they felt they could do what they liked,” he says. Then there was the shambolic announcement itself. News first leaked out through a Sky report before being followed up by a late-night press release that was heavy on the mooted financial benefits of the project — a focus that only fuelled fans’ anger about corporate greed — but light on details (where, for example, were the broadcast deals — the main source of revenue?). The member clubs issued insipid facsimile statements before apparently being sworn to omerta until the capo finally snuffed it 48 hours later.

Scrutiny has naturally turned to the PR firm behind the league and Inhouse Communications, run by Theresa May’s former spin doctor Katie Perrior and once described by Boris Johson as the “Fortnum and Mason of communications” (ironic, given the PM this week described the Super League as a “cartel”), was soon outed as the guilty party. But according to an Open Democracy report, Inhouse was hired just hours before the press release was published. Given discussions must have been underway for months, the total lack of planning is astounding and the blame, you feel, cannot be placed entirely with the flaks.

The botched launch has sparked speculation that the Super League was little more than a bluff designed to give UEFA a whiff of the clubs’ power ahead of planned changes to the Champions League. But this still would not explain the shambolic communications. With a well-planned campaign, the Super League could have sown doubts over UEFA’s grip over world football and presented its project as a fan-friendly alternative. Maybe then it would have worked. Instead, it merely cemented owners’ reputations as money-grabbing, blustering billionaires.

Despite some self-righteous claims to the contrary, the piety of football fandom is such that supporters are hardly likely to abandon their clubs over this controversy. But that’s not to say the teams will emerge unscathed. The Super League saga has already claimed the head of Man United boss Ed Woodward, and the rebel clubs could reportedly now be facing sanctions from both the Premier League and UEFA. The biggest takeaway from all this, however, is the value of good PR. The Super League clubs thought they were too big to fail, but their complacency simply proved a shocker of an own goal.

Is Netflix’s pandemic party finally over?

There’s always speculation about Netflix’s subscriber numbers, but first-quarter figures this week still came as a shock. While analysts were expecting a slowdown in growth as lockdown restrictions began to ease, the platform’s 4m new subscriber additions lagged well behind forecasts of 6m and were half the number it added in the last three months of 2020. The lacklustre figures sparked an 11 per cent fall in Netflix’s share price, wiping $25bn off its market value.

An end to Netflix’s bumper pandemic trading has been in the offing for some time, but it’s only now that we’re seeing evidence in the numbers. Aside from the obvious point that the gradual return to normal life will reduce the time spent binge-watching TV shows, Netflix has also struggled with delays in the production sector, which have in turn hit its content slate.

The quarterly numbers show the slowing growth came primarily from Netflix failing to add new customers, rather than existing ones cancelling their subscriptions (known as ‘churn’). In a sense this is good news for the company, showing people are not deserting the platform. But, as media analyst Ian Whittaker puts it, it also suggests that the “pool of new subscribers is drying out”. Add to this the fact that competition is heating up from rivals such as Disney Plus, which is forecast to take the crown of largest streaming service by 2025, and it seems Netflix is at something of a crossroads.

Content is, as ever, king, and victory in the increasingly crowded market will go to whichever platform consistently delivers the best shows. Yet there is also a question of how to fund this programming amid a budget arms race that’s pushing up production costs. Netflix has said it no longer needs to rely on external cash raises to fund its operations and has instead been slowly lifting its prices. But with more players in the game, there’s a limit to how much more consumers will be willing to fork out.

Instead, the Silicon Valley giant could look to find new sources of revenue. Analysts reckon foreign language content will become even more important, both as a way of attracting subscribers in new markets and due to the surprise lockdown success of hits such as Call My Agent and Lupin. It could also explore a new offering, with gaming and audio slated as the most likely candidates.

Netflix remains the most dominant power in the streaming market, and it’s not going anywhere. Besides, some of the challenges it faces are also hurting its rivals. But the latest figures show that if the streamer gets complacent, it could well catch a chill.

The algorithm recommends

- It’s been a good week for fans of litigation. Tiktok is being sued for billions over its alleged misuse of children’s data, while the Daily Mail has filed a lawsuit against Google over claims the tech giant unfairly pushed its stories down search rankings.

- The government has intervened in Nvidia’s $40bn takeover of British chipmaker Arm on national security grounds. Why? Find out here.

- Apple has taken another step forward in its noble quest to make the computer disappear. It seems hard to justify having a desktop computer these days, but when you see the pictures of the new iMac you’ll see what all the excitement is about.

Got a story? Drop me a line at james.warrington@cityam.com or on Twitter