Regulators beware: Why capitalism needs crisis

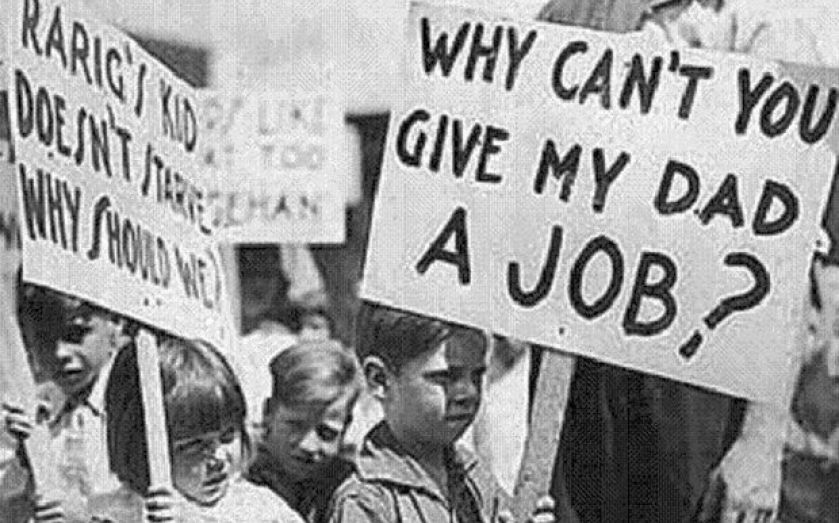

WE LIVE in a world riddled with black swan fatigue, and this piece does not propose to add to it. Still, the recent financial crisis and its continuing implications have invited hyperbolic comparisons, most notably with the 1930s. That decade is seared in cultural memory as the Great Depression – a traumatic time of economic distress and mass unemployment. Yet it was also one of the most successful eras for entrepreneurs in US history, with more fortunes created than in almost any other comparable period. Among the companies founded were Motorola (1928), KFC (1930), Tampax (1936) and Hewlett-Packard (1939).

This conundrum reveals some important truths. First, no country ever went bust forever. In the middle of even the most troubled economic environment, there are embers waiting to spark into life and produce future growth. Second, innovation is in our blood. Capitalism is a continual process of creative destruction, where markets periodically clear out the old and replace it with the new. This agnostic dynamism is fundamental to our ability to adapt to a changing environment and find ways forward.

In short, economies are dynamic pools of exchange beset by continual paradigm shifts, thanks to the inconsistent behaviours of their human constituents. These shifts may be good – innovation and booms – and may be bad – over-extension and busts. Common to both is the complex web of money and credit that binds us together.

On the one hand, this can help society to grow faster by accelerating change, enhancing trade and raising the quality of life. Yet these flows of capital are also driven by human bias and crowd behaviour. By unconsciously following the incentives laid out before us and the advice of others, we create herds that – given enough good fortune – will choose to invest not just in productive assets but also in unproductive assets.

The implication is that boom and bust are part of our socio-economic DNA.

This is not surprising. The entrepreneur and financial speculator are two facets of the same human nature. The blinkered taking of risks, the relentless focus on the here and now, the ability to persuade your peers of your vision – these are all qualities we extol in entrepreneurs for growing economies. Yet we deride the same in speculators as vices that cause financial contagion and strain societies. The delineation is merely the result of taking snapshots of the same person at different times.

History concurs. Progress is often linked to the capacity for error. Speculation may cause bubbles if unchecked, but taking imprudent risks also leads to advances. The rise of the internet spawned an infamous dotcom bubble. However, that same bubble also financed a paradigm shift in the global exchange of information and social interaction that defines our world today.

In 377 BC, 10 out of the 13 Greek city-states linked to Athens defaulted on their loans from the Temple of Apollo at Delos. It was the first recorded financial crisis. Over the prior century, a complex network of trade, military alliances and credit had fuelled remarkable growth, outstripping the Malthusian constraints of the harsh Greek terrain.

The result was a golden age with a pervasive influence. This was the stage for famous thinkers such as Socrates, Plato and Sophocles. Hippocrates, the father of medicine, was born. The Acropolis was built. The foundations of democracy and the proto-welfare state took shape.

Plentiful money and growth allowed Athenians time for leisure and encouraged closer interaction with enormous benefits. But this web of money binding society was also capable of transmitting negative shocks and eventually led to the first known sovereign default.

The golden age of Ancient Greece and the first financial crisis were twin sides of the same evolving complexity. The complexity that powered innovation and boom also accelerated contraction and bust.

Today, policymakers are united in their desire to see sustained growth and financial stability. They have failed to understand that the two cannot coexist and their dogged pursuit achieves neither. Rather, they have only evolved a new complexity that is ridden with misplaced incentives and is far more fragile, as evidenced by the worrying confluence of a property boom and banks that are too big to fail.

Our understanding of how an economy works must be rebuilt. Short of disowning progress, we cannot remove change. Even then, we cannot excise the ebb and flow of emotion that resides within us. But by understanding these human drivers, we can prevent the inevitable next recession from becoming something far more scarring.

Dr Bob Swarup is a fellow at the Institute of Economic Affairs and author of Money Mania: Booms, Panics and Busts from Ancient Rome to the Great Meltdown (Bloomsbury, 2014). swarup@camdorglobal.com.