| Updated:

In praise of solitude: What does time alone mean to you?

Our phones never stop ringing. Emails flood our inboxes. Meetings are an integral part of our working lives (not to mention pre-meetings and de-briefings). Smartphones keep us connected with our friends and family during the day and our bosses when we’re at home at night. In 2015, most of us can quite honestly say they we are never truly alone.

But we’re a species descended from nomads, creatures who were once upon a time engulfed in darkness and solitude as soon as the sun set. What is this unprecedented level of connectivity doing to our psyche? Is it one of the crowning achievements of the 21st century, or a psychological poison slowly corroding our brains? We asked people from various walks of life, from artists to psychologists, what “solitude” means to them.

Additional reporting by Alex Dymoke and Melissa York

ROBERT J COPLAN

PROFESSOR OF PSYCHOLOGY AND EDITOR OF ‘THE HANDBOOK OF SOLITUDE’

The idea that solitude is detrimental can be traced back to biblical times: “the Lord God said ‘It is not good for the man to be alone’ (Genesis 2:18)”.

There is support for this view in modern psychology: neuroscientists think loneliness is not only bad for our well-being, but also takes a toll on our physical health; developmental psychologists say excessive solitude in childhood can lead to lasting emotional issues; social psychologists say human contact is a basic need.

But solitude can also be a context for self-discovery and self-realisation, a restorative haven for the mind (and soul), and a unique venue for solving problems and fostering creativity.

Whether we experience solitude in a positive or negative way, of course, depends on the individual. People who are shy often desire social contact but fear and self-consciousness prevent it, which can lead to solitude tinged by loneliness and worry. Introverts may enjoy a night out with friends, but such experiences can trigger a subsequent retreat to solitude to “recharge”. Conversely, extraverts may have difficulty tolerating time alone and seek the company of others to bolster their energy reserves. A key factor is agency. When imposed, solitude usually comes at a cost. When chosen, it can be desirable, an experience that affords us a variety of benefits.

Many questions surrounding solitude are still being answered. Does it have different implications at different points in a person’s life? Does its meaning and impact differ across cultures? [note: the short answer to both of these questions appears to be a resounding “yes”]. Finally, although we may at times find ourselves alone in a crowd, alone with nature, or alone with our thoughts, rapidly evolving technological advances intend to connect all of us – all of the time – to social and informational networks. This leads to the question as to whether any of us will ever truly be “alone” in the future.

Adapted from The Handbook of Solitude: Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation, Social Withdrawal, and the Experience of Being Alone, New York: Wiley-Blackwell

No.2, a shot of the moon taken by Josh Shinner

JOSH SHINNER

ASTROPHOTOGRAPHER

I think a lot of people need to counteract the frantic nature of life in London by occasionally escaping, whether it’s to the seaside, the hills or, in my case, the moon. Exploring space through a telescope on my roof in North West London is my way of balancing out the busy days. Looking at the moon, a lifeless rock a quarter of a million miles away, you can almost feel the solitude being reflected back at you through the lens. It makes London seem quieter, gives you a chance to think.

In my day job I photograph models, actors and musicians. There’s a whole team involved, and it’s very much a collaborative effort to get to the final shot. Photographing the moon is a stark contrast – there’s no brief, no shot list, no pressure. It’s relaxing, almost therapeutic. Don’t get me wrong, I love my day job, but occasionally stepping away from it and losing myself in space helps me focus. The other reason, of course, is that it’s frowned upon to drink whiskey on set, whereas it’s practically essential in astrophotography, which is a chilly business.

On my wall I have a print of one of the first moon shots I ever took; it’s a nice reminder that one’s little world isn’t everything and that sometimes you need space to get a little perspective.

Limited edition prints are available at mainlythemoon.com

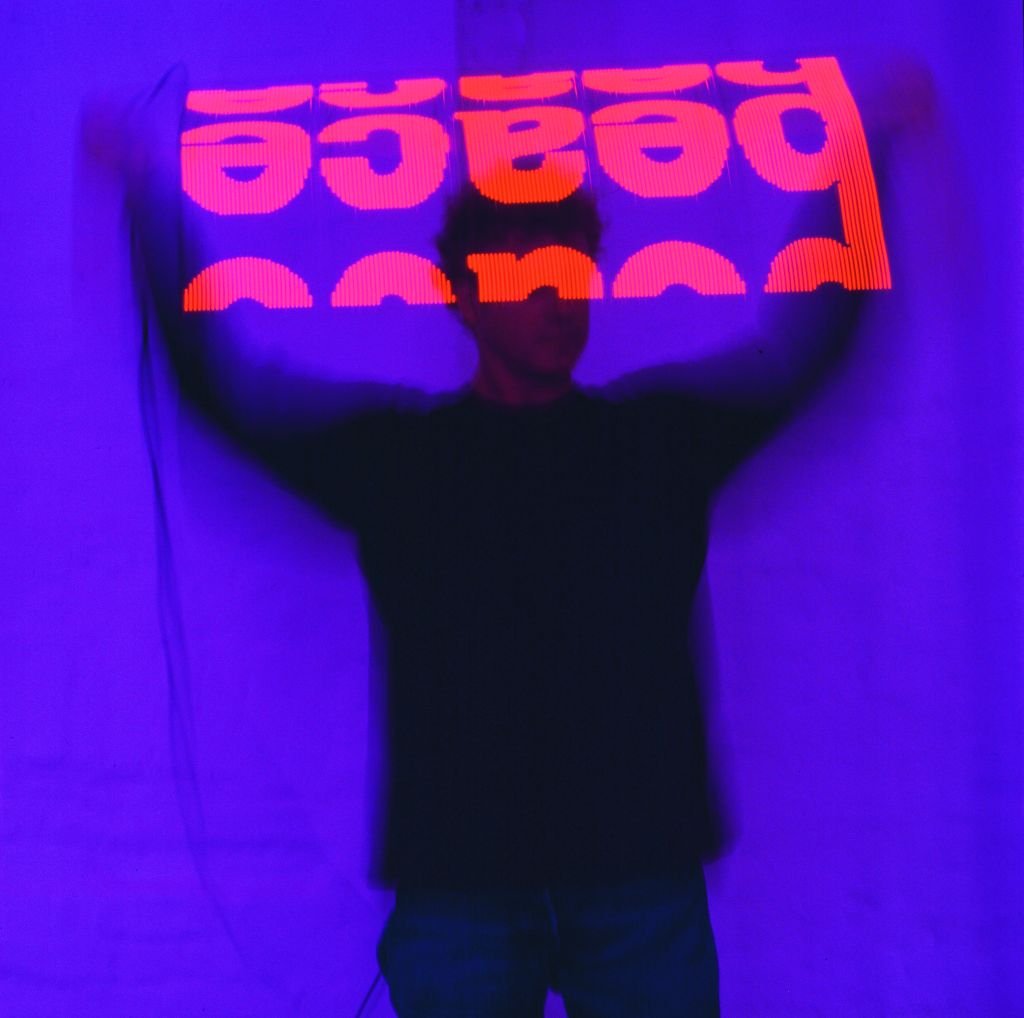

A piece by artist Chris Levine, who creates installations and portraits using light

CHRIS LEVINE

ARTIST WHO USES LIGHT TO CREATE PORTRAITS AND IMMERSIVE EXPERIENCES

Inventor and electrical engineer Nicola Tesla – one of the greatest minds that ever lived – said his best ideas came out of stillness. This is something I can relate to; some of my best ideas have come to me in the serenity of meditation.

There was a time when I would fantasise about solitude. I used to imagine a locked, white box and at times of high stress I would retreat there from the noise of the world and my own thoughts. Away from everyone and everything, I found I could accept the world how it is, instead of wrestling with how I wanted it to be.

These days, I no longer need the box. Over the years I learned how to meditate. I found a sense of peace, an internal field of awareness; anyone can access it, simply by learning some basic techniques. Meditation allows you to access a stillness where your body recalibrates and accepts what is. It’s a beautiful, serene place and a creative one, too, somewhere ideas and perspectives flow and take form.

Stillness is something I actively try to induce with my artworks. In my latest show, The Geometry of Truth at The Fine Art Society in London, I invite the viewer to step out of life’s noisy kaleidoscope using light installations. The work is a meditation on colour and its power to evoke a kind of silence, enveloping the viewer in an immersive and meditative environment. From a position of solitude I believe we evolve into more productive beings.

The Geometry of Truth is at The Fine Art Society from 24 April – 23 May

Endurance runner and long distance swimmer Sean Conway

SEAN CONWAY

ENDURANCE RUNNER AND THE ONLY MAN TO SWIM LAND’S END TO JOHN O’GROATS

I don’t actively look to spend time alone. Solitude is a by product of the solo adventures I do. People always ask me, “what do you think about when you spend months at a time on the road or in the ocean?”

The answer is complicated because I think of everything and nothing at the same time. It’s hard to explain; I go into a kind of trance, flowing from conscious thoughts about food, where I’m going to sleep that night, who I’ve met and who I might meet, to unconscious thoughts about life, the universe, the reason for existence. It sounds deep and meaningful but no single thought ever really has time to register before my brain has moved on to the next thing.

At first I used to fight it, to force myself to think about specific things, often to justify why I’m face-down in the water hundreds of miles away from my friends and family: “This is all to ‘find myself’ or to question lifestyle stereotypes”. Now I just let it flow; some of what goes on in my head is useful but most of it is nonsense.

This isn’t to say I don’t appreciate solitude: I find the time and space away from everyone and everything therapeutic – I can let my imagination run wild. It’s a detox of the mind and although I’m unlikely to find the solution to world peace, I’m always a lot happier when I get home, and isn’t that what it’s all about? I often become introverted after large chunks of time alone but I don’t let it worry me. I’ll happily go to a pub, sit in the corner and keep myself to myself, just peoplewatch and listen to music. When I’m in this mood I rarely feel the need for company.

Sean Conway: Running Britain will be broadcast on Discovery Channel early this summer as part of the channel’s Make Your World Bigger campaign

SVEN EHMANN

CREATIVE DIRECTOR AT GESTALTEN, PUBLISHER OF ‘THE NEW NOMADS’

People often think of “solitude” as disconnecting from society, hiding away with nothing but your thoughts. But technology means it’s now possible to distance yourself from certain aspects of modern life – especially office-based, urban life – without becoming a hermit. You can have physical solitude without psychological solitude.

I’ve followed the rise of the “new nomad”, a generation of professionals who are establishing a new standard of independence. They usually work freelance or run their own businesses, they use digital tools and work predominantly online; it doesn’t matter whether they’re sitting in a cubicle in Manhattan or a beach in Bali. I don’t think these people are retreating from society in general, but rather the classic idea of society. In fact, their mindset is often open and very social.

You can be an entrepreneur in a souped-up caravan on the coast of Chile or a modernist glass chalet on the side of a mountain. It does, however, open up some interesting questions: if there is no longer a place you call home, where would you vote and what would you vote for? Would you invest time and energy in social causes or would you only care about your next yoga session?

I think we’ll see this kind of lifestyle become more and more popular. Just getting away from densely packed urban spaces is a very appealing thought.

The New Nomads, published by Gestalten, is out now priced £35; shop.gestalten.com