Napoleonic cellars and Peaky Blinders: How the old merchants of St James’s Street are fighting to stay relevant

Reserved, polite and unashamedly old-fashioned, the shop-owners of St James’s Street do not offer many similarities with the brash retail bosses we so often see in the news.

Unlike Mike Ashley or Sir Philip Green, they are not waging takeover wars or stirring up corporate controversies.

They are cautious in their ambitions, and conservative in their tastes.

But just like every other high street boss, these merchants of the West End are now faced with new threats to their survival.

From higher business rates to a rise in online shopping, major shifts are putting new pressures on London’s oldest retailers.

As a result, the need to branch out beyond their small but loyal base of well-heeled (and often aristocratic) customers has become more critical.

But that means entering markets with new trends, new tastes and new demands – a process that the old stalwarts of St James’s are currently trying to navigate.

“We try to keep moving” laughs Edward Rudd, a third-generation family member of Berry Brothers and Rudd.

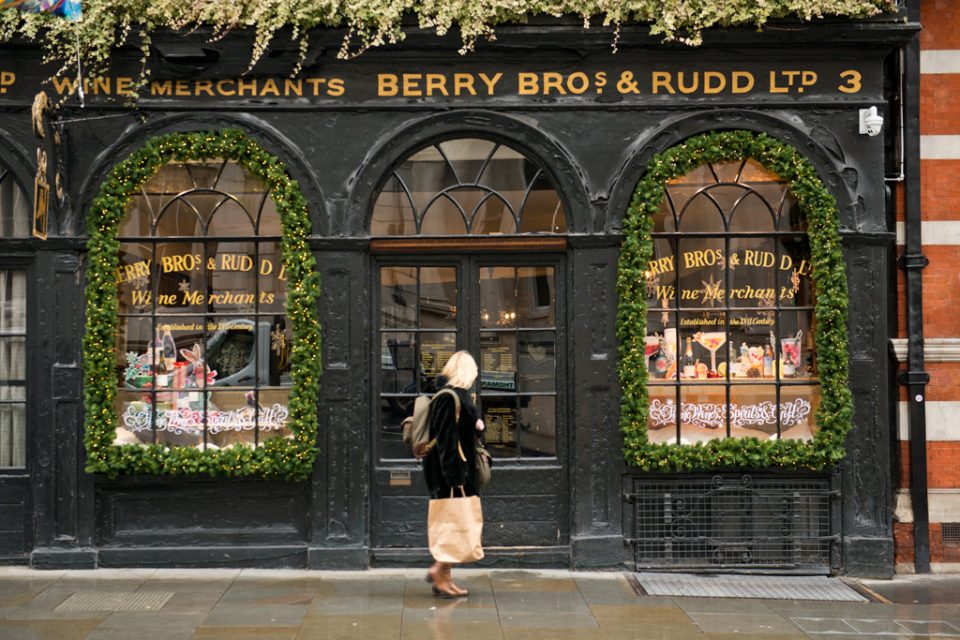

Having traded from the same shop since 1698, Berry Brothers is Britain’s oldest wine and spirit merchant.

It boasts two royal warrants, provides wine for the Royal Opera House and counts William Pitt the Younger and Lord Byron among its past customers.

But underneath centuries-old wooden ceilings, Rudds and Berrys are thinking more about the future than the past.

“People want to drink less now. There’s definitely a no-and-low alcohol trend among millennials”

How the hell does a wine merchant cater to a new generation of health-obsessed teetotallers?

“We’re looking at dipping our toes in the non-alcoholic market” says Rudd as we take a seat in the firm’s parlour, a cosy room used by former generations as a hideaway from customers.

Rudd also echoes what many in the wider retail industry are noticing: younger buyers want more than a product – they want an experience.

These experiences, termed by Berry Brothers as ‘events and education’, have become an increasingly important part of the business.

The firm hosted wine tastings and dinners for over 25,000 people last year, many of which were held in its dimly-lit Napoleon Cellar (where the future Emperor Napoleon III held clandestine meetings to plot his return to France).

Rudd also claims the business saw another major trend that has since rocked the retail industry: the coming of the internet.

“We were the first wine business in the UK to have a website…and at one point we were the oldest company in the world be on the internet” he says.

Read more: A peak inside Goldman’s London HQ

Yet the company has not been able to deal with every headwind coming its way.

“Brexit paralysis has been really tough.

“The biggest effect of all is the exchange rate. We’re hedging as much as we can but that is the most painful part of it – in terms of buying wine from Europe, the exchange rate hurts. The margins on fine wine are not big so the swing of a few per cent makes life really tough.”

After leaving Berry Brothers I head up the road several doors and step inside world’s oldest hat shop, where a British TV drama series is the current cause for celebration.

“We call it the Peaky Blinders effect,” says Roger Stephenson, deputy chairman and a 7th generation employee of Lock & Co. Hatters.

According to Stephenson, the Peaky Blinders series is causing a boom in tweed flat cap sales.

Revenues have also been boosted by a comeback of the bowler hat, once worn by City gentlemen working in finance but now popular among Shoreditch hipster-types, he says.

Having been founded in 1676, Lock is one of the oldest of the old on St James’s Street, but its focus also appears to be entirely on the present.

“When I started it was a much older market of clients, but now, because of things like style influencers, we see much younger people thinking about hats that help to finish off their look”, says Stephenson, who reckons that the average customer has fallen from over 50 to over 30 in the last three decades.

Inside the Berry Brothers and Rudd shop

Master Hatter Jayesh Vaghela

A conformateur

A bootmaker at John Lobb

John Lobb on St James’s Steet

Gone are the days when the family-owned business can rely on a steady influx of aristocratic types.

Instead, the group is branching out: selling a quarter of its orders online, often to customers abroad, while also hoping to attract more interest through its products being worn by celebrities on red carpets and in films.

After leaving Lock I pay a visit to its nextdoor neighbour, John Lobb, the bespoke bootmaker where shoes typically go for £5000 a pair.

Even by the West End’s conservative standards, Lobb feels particularly cautious when it comes to embracing change.

“We haven’t yet embarked on the social media front” admits Jonathan Lobb, the firm’s softly-spoken fifth-generation manager, whose desktop computer looks almost as old as the wood-panelled premises.

With its cosy red carpets and old cabinets of Wellies and Oxfords, there is hardly a trace of modernity in the shop.

Perhaps that is why it appears to be so popular among Japanese clients, whose tastes for tradition seem to be evident in almost every shop on St James’s Street.

Compared to Lock, Lobb feels far more reserved when it comes to chasing business; there is no talk of an Instagram boost or film-related sales, and not much time for online services as a whole.

Rather, Lobb says the firm is hardly operating any differently to how it has done in past generations: “You need to be able to see the customer”, he insists.

Amazon doesn’t seem to think so.

But then again, Amazon has not been around for hundreds of years.