Move over, US: time for a new stock market leader?

The US has dominated stock market returns globally ever since the Global Financial Crisis. But nothing lasts forever…

Dominance in almost any walk of life goes in cycles. Just ask Manchester United fans or MySpace users…

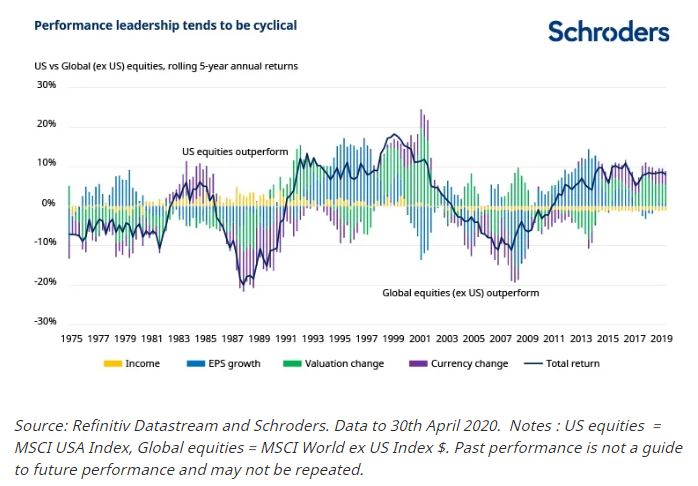

Well, the same can be said of markets. They also go through periods when certain regions (or companies) seem to have an insurmountable advantage. Most recently, it’s been the US – whose stock market has dominated the past decade.

Since the Global Financial Crisis, the annualised return from US equities has been a hefty 13%, far outstripping global equities’ 6% annualised return (as measured by the MSCI USA Index and MSCI AC World ex US Index respectively, in US dollar terms).

Even in the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak, this trend has remained intact, leading some investors to question whether they should even bother owning any shares from outside the US at all.

However, those who expect this trend to continue over the coming decade could be disappointed. After all, the winners and losers, both within and across markets, fluctuate over time. This time shouldn’t be any different.

A shift towards non-US equities is arguably long overdue. And while timing this inflection point is difficult, all the signs suggest that gravity will eventually bring US equities back down to earth.

For more:

– Video: Why do markets rise when economies slump?

– Read: Which stock markets look ‘cheap’ after the rapid rebound?

US profits advantage has disappeared

The main reason US equities have done so well is because of their superior profit growth. For example, US earnings-per-share (EPS, a company’s profits divided by the number of its outstanding shares) grew at 17% per year. Outside the US this figure was just 7%.

The problem is that this earnings growth advantage has pretty much disappeared. Since 2015, US equities haven’t outperformed because their profits have continued to be superior. In fact, nearly all of the relative outperformance has been driven by investors being willing to pay ever higher valuations for stocks, combined with dollar strength. Valuations and the dollar can always climb higher, but not indefinitely.

Markets have justified this valuation premium because US firms have been able to reinvest their profits at increasingly higher reinvestment rates. That is, they’ve become more efficient at generating income using their shareholders’ capital. However, the secular forces supporting this trend such as globalisation, lax anti-trust enforcement and international tax arbitrage have either stalled or are reversing.

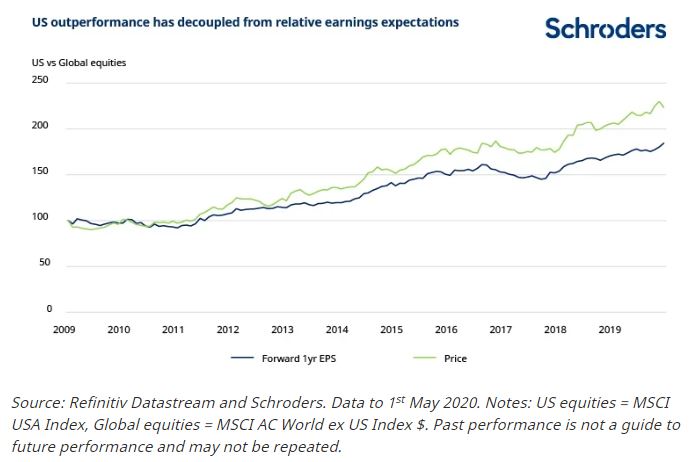

Share prices are no longer in sync with earnings

For most of the post-crisis period, US outperformance has moved in tandem with expectations for their future profits. However, recently the gap between relative returns and earnings expectations has widened significantly.

This is not sustainable. At some point, earnings expectations will need to catch up or US stock prices must correct.

The price you pay matters for future returns

One consequence of this is that valuations are stretched to levels which would have historically foreshadowed low returns for US equities versus the rest of the world.

For example, US share prices trade at 25 times their cyclically-adjusted historical earnings (CAPE) compared to only 13 times for global equities. This widely-used valuation measure divides a stock market’s value or price by all the companies’ average profits over the past 10 years. A low number represents better value.

The long-term outlook for the US relative to other markets no longer seems so attractive.

The winner’s curse

The US is home to some of the most successful companies in the world, including firms such as Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, Google and Facebook. Together, they have delivered significant profit growth and technological innovation.

However, these companies have become so large that they are essentially driving the market. Their combined weight (as measured by their market cap – the value of all their shares) has more than doubled from roughly 8% of the S&P 500 Index in 2015 to nearly 20% today.

A market this narrow should give cause for concern. The bigger they get, the harder it becomes for them to replicate that performance. This is because once a company dominates an industry, it can only grow as fast as the market size grows.

The only way they can continue to justify the expectations placed on their growth is by developing other game-changing products, or using their existing resources to branch out into other services. But there is no guarantee they will succeed.

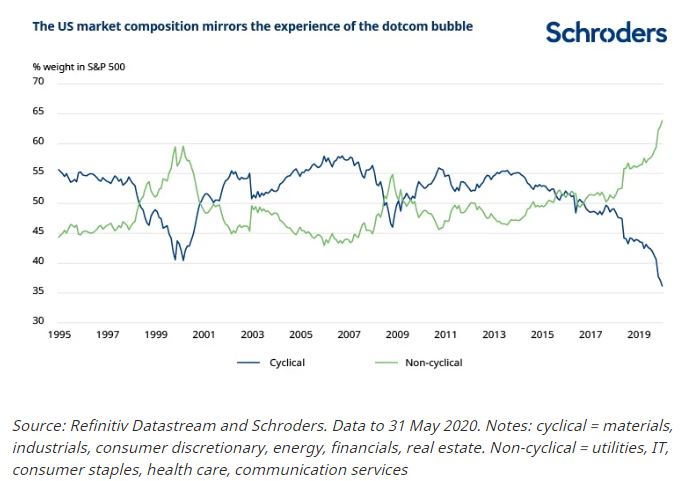

Cheaper exposure to an economic recovery sits outside the US

Global equities are especially attractive now given their higher economic sensitivity. For example, as at 31 May 2020, cyclical (economically sensitive) stocks represented 58% of the MSCI All-Country World ex US Index, but only 36% of the S&P 500 Index.

Typically, cyclical stocks perform best after the economic cycle bottoms, so a lower relative weighting in this segment could limit the rebound in US equities once global growth recovers.

Avoid putting all your eggs in one basket

The last decade has belonged to the US, but as we mentioned at the beginning, history shows that winners and losers go in cycles.

Although we can never really claim to know in foresight, the way we do in hindsight, why and how these leadership cycles shift, we do know that conditions in markets are ripe for a reversal.

This means investors in equities may be wise to look beyond the US’ borders for the decade to come.

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.