Job title inflation: When will it end?

While less is more when dressing for work, that same logic hasn’t yet reached corporate uplifts

MARK Zuckerberg is guilty of it. So were the tieless bunch of world leaders who assembled at the G8 summit last June. Yet the much-criticised phenomenon of successful people dressing down – eschewing shirts, ties, suits, and proper shoes for whatever falls out of their wardrobe – apparently has some justification. A recent study from Harvard Business School asked luxury shop assistants in Milan what they thought of people walking in wearing gym clothes. The noncomformists, particularly when their behaviour was seen as a form of conspicuous consumption, were perceived as of higher status and greater competence.

But if less is more sartorially, why does job title inflation show little sign of abating? In 2012, the Resolution Foundation released We’re All Managers Now, and confirmed what many already knew. An increasing number of people with “senior sounding job titles” earn middle ranking wages. In retail, for example, the proportion of managers earning less than £400 a week rose from 37 to nearly 60 per cent during the 2000s.

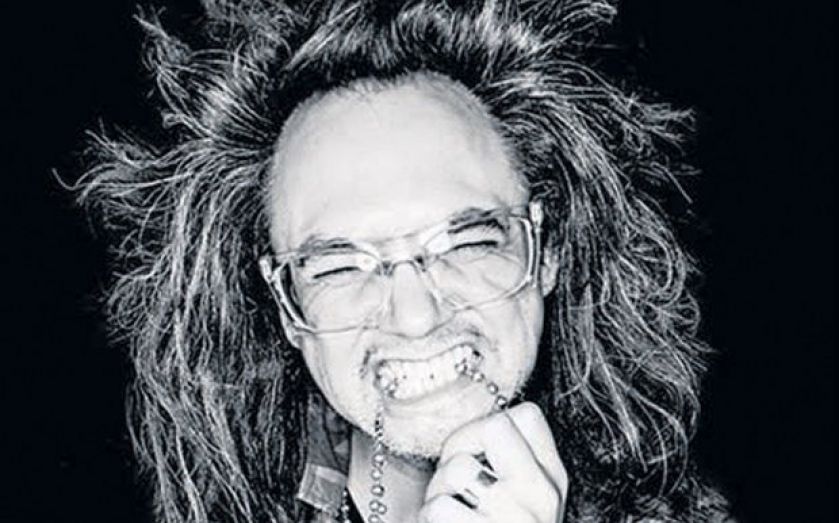

And in big corporates, the situation is surely even worse. For all the fuss about new culture secretary Sajid Javid being Chase Manhattan’s youngest vice-president, Goldman Sachs now reportedly has 12,000 of them. On the JP Morgan operating committee, there are no fewer than five chief executives. And the tech giants win all the prizes for job “fluffing” creativity: David Filo, Yahoo’s co-founder, is also its chief Yahoo; Microsoft has a chief envisioning officer; AOL’s digital prophet is called Shingy.

What has driven this? Some think companies use title “uplifts” as a way of hanging on to staff during difficult times – an alternative to a pay rise. Others, including professor Betsey Stevenson, have argued that it’s a consequence of flattened hierarchies: if the corporate ladder is no longer so steep, yet employees still think they should get a promotion, firms hand out better titles to make staff feel valued.

Wharton’s Peter Cappelli says job title inflation originated in the 1970s, in the sorry era of wage and price controls. Companies couldn’t give employees a pay rise higher than a centrally-determined level, so souped up role descriptions took on some of the heavy lifting. Firms even use titles as a form of signalling. When you have a chief diversity officer and a chief learning officer, we know you really care.

Like those corporate empire-builders in hoodies, however, some have rowed back against the vicious circle of competitive up-bidding. Google has even been criticised for the crime of job title deflation. You can see why it might want to pop this particular bubble. It’s a problem when no one knows what you do, no one knows which jobs they can apply for, language is brutalised for the sake of keeping staff happy, and titles effectively become meaningless. Yet perhaps it’s wishful thinking to expect our “directors of first impressions” to suddenly become receptionists again.

But in the cause of revealing some of the greatest sinners, and courtesy of the Plain English Campaign, here is a small selection of the worst – possibly apocryphal – culprits, along with their definitions:

■ Space consultant: estate agent.

■ Ambient replenishment controllers: shelf stackers.

■ Foot health gain facilitator: chiropodist.

■ Knowledge navigator: teacher.

■ Head of verbal communications: secretary.

App to protect your secrets

My Secret Folder

£0.69

If you use your iPhone or iPad for work, fear theft or even just allow your children to use your devices, My Secret Folder may be for you. It allows you to store contact details, notes, and files secretly and securely behind the app. And if anyone attempts to get past its sophisticated password protection, your device snaps a picture of the culprit.