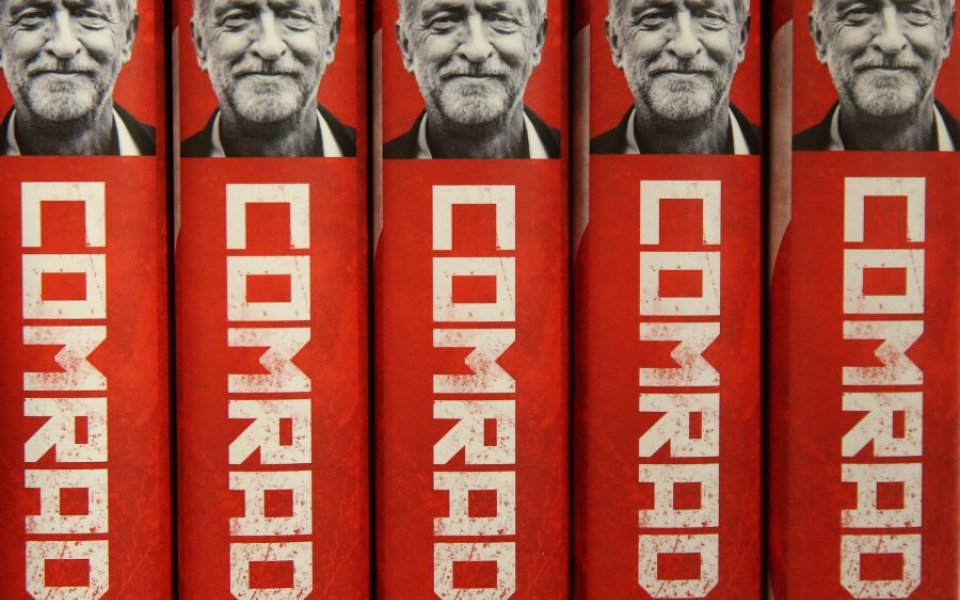

Jeremy Corbyn could already be harming your investments

Corbynmania may have reached a crescendo with the election of the Labour leader last year, but the ructions caused by this political phenomenon have not gone away. With Jeremy Corbyn taking an increasingly firm grip of the Party, reshuffling the shadow cabinet and looking to change Labour procedures to enable party members to have more influence over policy, what should investors make of the Labour leader and his shadow chancellor John McDonnell?

Corbyn and McDonnell have clearly set out their stall as wanting a more command economy and greater redistribution from the “haves” to the “have nots” as a matter of principle. Personal investors, meanwhile, are actively involved in supplying capital to British business. A recent ONS report, for example, showed that 30 per cent of Aim companies’ share capital is held by personal investors. Hundreds of thousands of investors control their own investments through self-select stockbrokers and millions more have a direct stake in UK plc through their pensions. So by being owners of capital, personal investors may consider they have much to fear from Team Corbyn.

We have identified three areas where we believe the Labour leadership could already be having an impact today.

Renationalisation

The new Labour leadership has a stated desire to renationalise certain industries and this could include plans to reverse the planned privatisation of Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS).

Markets set prices based on a number of factors. One of those is risk – higher risk typically being reflected in a lower price or a discount. If the market perceives that there is a risk to publicly-traded enterprises from enforced renationalisation, it is reasonable to expect this to be reflected in the price. The scale of that discount depends on the likelihood of the risk materialising. If the market believes the electoral prospects of a Corbyn/McDonnell-led Labour Party are improving and victory is more likely, that discount could become significant.

In the near term, George Osborne has indicated that he plans to reprivatise RBS. Arguably, if the market perceives there is a risk of that sale being reversed by a subsequent Labour administration, this may impact the price Osborne can sell RBS for as the market prices in the risk of those assets being renationalised in the future.

Union action

When they were elected to lead the Labour Party, Corbyn and deputy leader Tom Watson both spoke of the umbilical link between Labour and the trade unions. That link had weakened under Tony Blair – and even arguably under Ed Miliband, most evidently through the changes to the voting rules in the leadership election itself, removing the union’s block votes.

Corbyn won the leadership by setting out a different agenda to the other candidates, galvanising the leaderships of the trade unions and energising sections of the population normally disaffected from politics.

A re-energised trade union movement, emboldened by greater visible support in Parliament, may become more militant. With the government legislating on new strike laws and welfare curbs, as well as maintaining a tight control on public sector pay, this will likely result in a significant increase in co-ordinated strike activity.

This could have a direct impact on the performance of those businesses with highly unionised workforces, including companies such as Royal Mail and G4S. It may also have an impact on businesses which supply into the public sector, should the requirement for those services or the ability to deliver them be impacted by any strike action.

Capital Taxes

Finally, Corbyn desires to see more vigorous redistribution of income and wealth. Policy detail has already included indications of higher income tax rates for higher earners, at the very least including the reinstatement of the 50 per cent top rate band of income tax. On corporate taxes, policy is less clear, with statements focused on getting corporates to pay the taxes due rather than specifically raising rates.

But the obvious place for those seeking redistribution to turn is capital taxes, in particular capital gains tax or broader asset-based taxation. We saw this at the last General Election, with Liberal Democrat proposals for a “mansion tax”. It is not unrealistic in the context of Corbyn’s avowed intention around redistribution to suggest that this could see the Isa limits and regime challenged, reduced tax incentives or increased taxation of pension contributions and savings, and capital gains, stamp duty and other asset related taxes increased.

This may cause personal investors to reconsider their appetite for investment and make equity investment significantly less attractive.

The openness, honesty, and principles of the Labour leadership are refreshing and clearly appealing to many.

But personal investors have much to be wary of. They provide critical capital flows which are helping to support British business, return the economy to steady growth, and provide new jobs and employment for many. Policies based on renationalisation, increased unionisation of the labour market and redistribution of wealth are all going to be of concern.