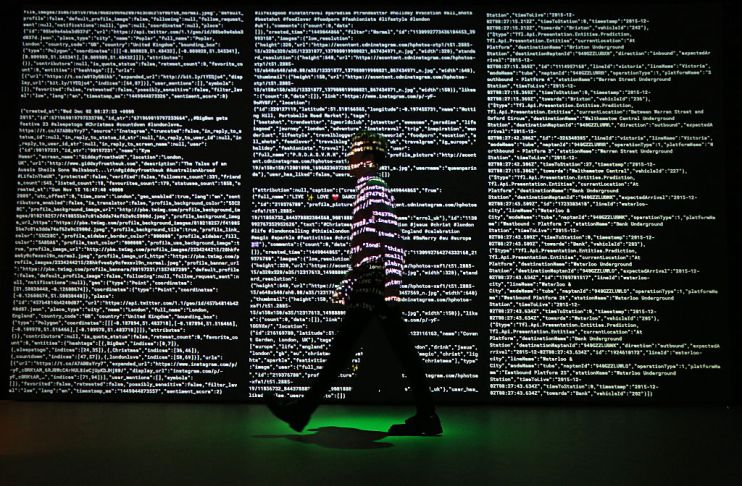

It may not be edge-of-your-seat, but preventing the AI dystopia starts with good data

The power and dangers of AI dominated conversation in 2023, but we won’t get anywhere without focusing on data, writes Nigel Shadbolt

Last year was the year AGI, or Artificial General Intelligence, became mainstream. Some of us tried out generative AI to help with homework, summarise text, or create social media posts. The technology was even featured in the King’s Speech. Yet a prevailing dystopian narrative often overshadows its benefits.

AI’s rapid deployment is far outpacing legislative and ethical frameworks, resulting in Big Tech companies being accused of ‘marking their own AI homework’. The US responded by getting tech giants – including Amazon, Google, OpenAI and Microsoft – to sign a “landmark” voluntary agreement which allowed independent security experts to test their latest models. In the UK, Rishi Sunak has announced his intention to set up the world’s first AI safety institute which will assess national security risks associated with the technology. Just in the past week US, UK and more than a dozen other countries unveiled an international agreement on how to keep artificial intelligence safe from rogue actors, pushing for companies to create AI systems that are “secure by design”.

Governments around the world entered an unofficial race to see who could place themselves at the forefront of AI regulation. A coup for the UK was hosting the inaugural AI Safety Summit at Bletchley Park. The gloomier aspects of the technology were discussed at length with the Prime Minister (PM) quoted as saying AI could pose a risk to humanity on the scale of a nuclear war. For many, though, the most concerning thing was the exclusion of communities likely to be the most affected by AI – those whose jobs could be displaced, or who could be negatively affected by algorithmic decision making on things like insurance, bank loans or benefits.

Governments around the world entered an unofficial race to see who could place themselves at the forefront of AI regulation. In the UK, Rishi Sunak explained the UK’s strategy by posing a question about how we could “write laws that make sense for something that we don’t yet fully understand”. I discussed this conundrum at the Open Data Institute Summit in November with my co-founder, Tim Berners-Lee. Our conclusions were that transparency in AI models and the data they use is essential to be able to evaluate them. Furthermore, AI needs to be scrutinised by people who understand it, and it’s likely that these individuals do not work in politics.

Public concern has continued, especially in relation to the potential impact of AI on employment. Such fears helped fuel a 146 day strike from the Writers Guild of America and a Getty images lawsuit against Stability AI. Yet, this industry had already adopted generative AI to produce outstanding imagery, and even award winning fine art. As generative AI grew, new tools emerged to protect originators’ interests such as Nightshade, which could ‘poison’ data connected with human work and confuse AI art models – eroding their ability to generate meaningful images.

Also hitting the headlines was a concerning undercurrent about data literacy. An annual survey of Fortune 1000 companies plus global data and business leaders showed that “data, analytics, and AI efforts have stalled — or even backslid”. The UK’s digital and data skills shortages were highlighted by the Open Access Government as becoming an urgent problem and the civil service was flagged as having a particularly significant gap according to consultancy Global Resourcing.

Looking ahead to 2024

I’ve long said that there is no AI without data and there is no good AI without good data. AI’s power comes from data, and a solid data infrastructure is essential for safety. The data AI uses must be well governed, reliable and come with clear provenance.

With a General Election beckoning, I’d like to see the party manifestos acknowledging data as the feedstock of most recent technological developments and committing to collecting and distributing it responsibly. Equally important will be commitments to keeping human decision-makers in the loop when AI is used to make choices. If an algorithm has decided – even if only in part – the outcome of a loan application, an insurance claim or a recruitment process, there must always be a human with the expertise and the capacity to hear an appeal against that decision.

OpenAI’s leadership battle towards the end of last year showed the challenges that arise when seeking to develop AI at pace – challenges that include appropriate management and oversight. AI learns from human feedback and needs diverse and talented people to work with it. Schools and universities will be key to this. The education system is beginning to see AI as a lifelong tutor for everyone on the planet rather than a plagiarism enabler that must be outwitted. Hopefully, 2024 will see a data-literate generation blooming who can tell fact from AI-fiction and gather the skills to staff the job opportunities that will emerge in an AI augmented world.