Iran nuclear crisis: The sharks are circling and war is not impossible

IF THE conventional wisdom of the mainstream press could sum up the current state of the Iranian nuclear talks in one headline, it would absurdly read “Optimism as talks fail to end”. Even by their standards, this fails to pass the laugh test analytically. Instead, an alarmed pessimism must be the correct response. For after 12 years, including the last nine months of increasingly intense discussions, the Iranian nuclear crisis has hit a brick wall.

With a deal out of reach this week, both the Iranians and the P5+1 (the US, China, Russia, the UK, France, and Germany) have agreed to continue disagreeing about two major stumbling blocks: the number of centrifuges allowed in the future Iranian nuclear programme and the speed with which, after an accord, sanctions on the Islamic Republic would be lifted.

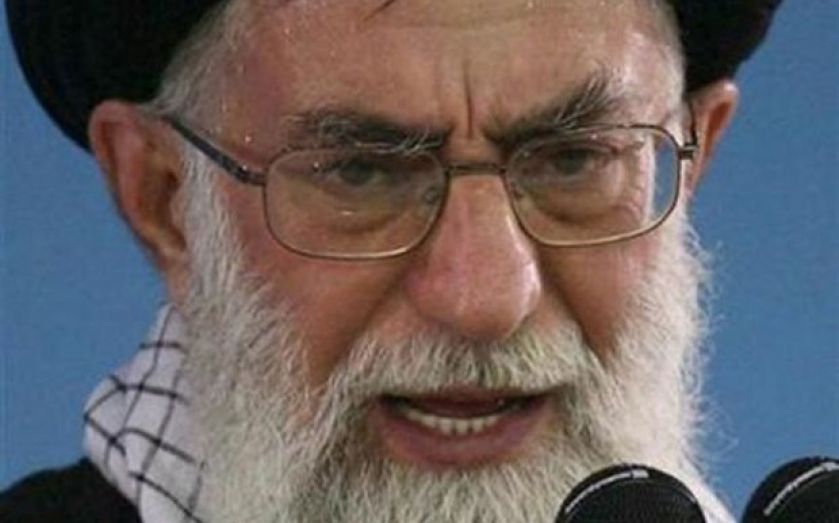

These substantive problems standing in the way of a deal are far from trivial. First, Iran (as was clearly stated by Grand Ayatollah Khamenei in July) wants the ability to develop a large, civilian nuclear capacity. Khamenei reckons this will require more than 200,000 of the current IR-1 centrifuges; the West’s counter-offer is that Iran will be allowed to possess a mere 2,000. So the negotiators, over this absolutely central point, are off by a factor of 100. This is a canyon-sized difference.

Second, the West wants any final agreement to stretch on for up to 20 years, with sanctions being repealed in bite-sized, incremental stages. Contrarily, Tehran expects the majority of sanctions to be suspended – by executive order, in the case of the US, as the new Republican-controlled Congress is highly unlikely to go along – almost at once, and for the whole process to be wound up in just five years. The two negotiating positions remain far apart.

Cheering on this failure, both Iran and the US have very strong vested interests – centred respectively around conservative religious clerics and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards (IRG) and irreconcilable hawks in the US Congress – who will not favour a deal under any circumstances that might be palatable to the other. For example, senator Bob Corker, the incoming Republican chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, stated in June that he would personally back new economic sanctions on Iran should a deal not be reached. Failure to solve the Iranian nuclear issue would immediately lead to a full-blown geopolitical crisis, with war a quite possible outcome. The stakes could not be higher.

And after a forest of false deadlines, the real sort is at last in view. This week, both sides agreed to keep the talks going until 1 March 2015, when a political framework deal ought to be in place. This is the real end game. For following the past few days’ failure to nail down an accord, the sharks are circling, particularly in America. The new Congress (which convenes in January 2015) probably has a veto-proof majority inclined to impose new sanctions on Iran should a deal not be imminent. Tehran has made it clear that any new US sanctions would end the talks. As such, the White House probably has one more chance to make a deal work, ahead of a hawkish Congress wresting the diplomatic initiative away from a weakened President Obama.

In other words, theoretically a deal can be done by March, but only just. But this much is for certain: the odds of such an accord are long. Failure, with all its ghastly consequences, must now be contemplated.