Inflation: ‘Relief’ for Reeves or a ‘temporary reprieve’?

Rachel Reeves could be forgiven for breathing a sigh of relief after this morning’s inflation figures.

Inflation figures always attract a lot of attention, but the stakes were sky high for the Chancellor after a week of turmoil in the gilt market.

The market consensus was for inflation to remain stuck at 2.6 per cent, but the risks were very much tilted to the upside. And if there had been a big miss, some commentators feared that the sell-off in gilts could have turned ugly.

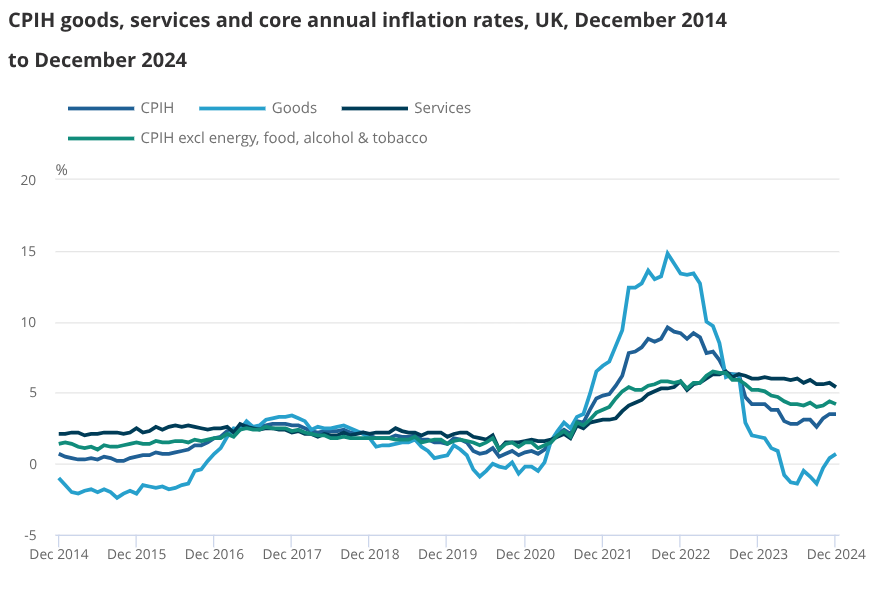

As it happened, the headline rate fell to 2.5 per cent. Services inflation, perhaps the most important metric of inflationary persistence, slumped to 4.4 per cent, its lowest level since March 2022.

Equities surged in response, led by housebuilding stocks, while gilts also recovered from their bruising start to the year.

“I think you can hear a sigh of relief coming out from Downing Street, the Bank of England and across financial markets as a whole,” Michael Saunders, a former rate-setter told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

But there was another word that some economists preferred: reprieve.

Put another way, Chancellor Rachel Reeves might not be out of the woods yet. So why were some commentators reluctant to join the collective sigh of relief?

The main reason for caution on this morning’s figures is that the sharp drop in services inflation was driven by the typically more volatile parts of the price basket, in particular airfares.

Last month’s 16 per cent rise in the price of airfares was the third lowest increase in the month of December since monthly prices were first collected in 2001, the ONS said.

“Part of the reason for the lower-than-usual growth may be because the return date for the European flights in this month’s index was Christmas Eve and the return date for long-haul flights was New Year’s Eve,” it suggested.

In other words, the ONS collected prices on days when demand is traditionally weaker, suggesting that the change in prices was driven as much the quirks of data collection as by changes in the underlying economy.

This single movement explained “about half” of the fall in core inflation, according to Pantheon Macroeconomics.

Hotel prices, which can also be very volatile (think back to Swiftflation) fell 1.9 per cent in December.

“The MPC will focus on measures of underlying services inflation that strip out hotel prices and airfares as well as other volatile CPI components to judge the underlying trend,” Rob Wood, chief UK economist at Pantheon said.

A number of economists think that inflation will rise to three per cent in the coming months, driven by a combination of a weaker pound, rising energy prices and the impact of the Budget.

“The dovish news today is a temporary reprieve,” Wood said.

Nevertheless, there was still plenty of good news in December’s inflation report.

Even excluding the erratic components, services inflation eased faster than many in the City had expected.

Analysts at Nomura said current rates of services inflation were compatible with meeting the two per cent target, even without the downward drag from airfares.

Similarly, HSBC pointed out that the monthly increase in core inflation was actually below the 2010-19 average for December, and would only have been “marginally above” when stripping out airfares.

So it looks as if things are slowly going back to normal, and most analysts predicted that the Bank of England would cut rates again next month.

“Bottom line, the Bank of England will likely feel emboldened to continue its easing cycle in February,” Sanjay Raja, chief UK economist at Deutsche Bank said.

The big question looking further ahead is how firms will respond to the Budget. Surveys suggest firms are planning to raise prices, which would slow the pace of rate cuts going forward.

But firms may struggle to pass on higher costs if demand in the economy continues to weaken, which would enable more aggressive rate cuts.

As Kallum Pickering, chief economist at Peel Hunt, said: “If the cause of the softer momentum in prices during December is that a sudden drop-off in demand has sapped firms’ pricing power, the risk to watch now is that incoming data on the real economy surprise to the downside”.