Hinge: the dating app that wants you to log off

At a time when most technology platforms are doing everything they can to keep you scrolling, Hinge has built its strategy around doing precisely the opposite: disappearing from your phone altogether.

Relaunched in its current form back in 2016 and now under the umbrella of Match Group, Hinge has positioned itself as the antidote to swipe culture.

With a minimalist interface, curated prompts and now-iconic tagline – “the app designed to be deleted” – Hinge has carved out a niche for seeking relationships in the digital era.

Its growth trajectory has been steady and strategic, with the app reporting double-digit expansion over the past year in the UK, US and Europe.

For Brits, it is now outpacing Tinder in install growth, according to mobile analytics firm data.ai – a notable feat given the rival’s longstanding market dominance.

“Our job isn’t to keep you on the app”, Hinge’s chief marketing officer, Jackie Jantos, told City AM at South X South West London. “It’s to get you off it”.

But in an era marked by waning trust in Big Tech, rising user fatigue and a broader reassessment of digital dependency, how does a platform that’s most successful when it’s no longer needed keep on growing?

The fall of the app economy

The decline of the once-dominant app economy became official in the latter half of 2024.

According to Ofcom’s recent ‘online nation’ report, for the first time in years, the use of all major dating platforms like Bumble, Tinder, and indeed, Hinge, declined.

While Hinge dropped 131,000 UK users, its rivals Tinder and Bumble lost 600,000 and 368,000 respectively.

Match Group, the US parent firm behind all three, has already felt the squeeze, announcing a six per cent global workforce cut last July, citing rising costs and waning user growth.

It blamed a generational seismic shift: Gen Z, it claimed, wants a “lower-pressure, more authentic way” of dating.

That’s been reflected in behaviour, with a survey of US students by Axios and Generation Lab revealing that 79 per cent of Gen Z use dating apps less than once a month.

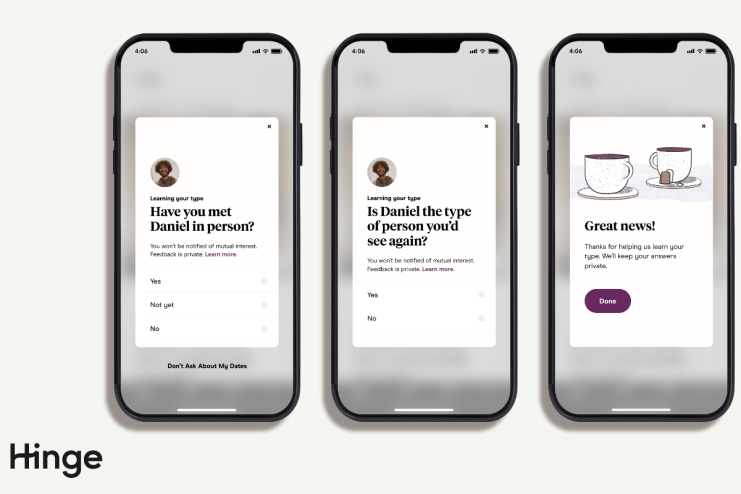

Whilst Tinder pioneered gamified swiping, Jantos claimed that Hinge leans on structured prompts, longer profiles, and a more “intentional onboarding experience”.

“It’s slow by design”, Jantos told City AM. “That friction is what gives people pause to reflect. It deters fake accounts and makes people think more deeply about how they present themselves”.

Hinge’s trust dilemma

Still, beneath Hinge’s more human interface lies the same algorithmic scaffolding which powers the rest of the industry.

Critics have argued that such systems, no matter how well-intentioned, often reinforce existing social hierarchies, from racial preferences to aesthetic biases and class-based patterns.

Yet, thankfully, in a podcast last year, Hinge founder Justin McLeod said that AI should not be used to replace people in the dating process. “This world of having AI bots as emotional companions,” he said, “I think is territory we really don’t want to go down.”

Most people, one hopes, would agree with him, but the appeal of AI is there. More than three-quarters of Gen Z dating app users report feeling emotionally, mentally, or physically exhausted by dating apps, according to a Forbes survey in July.

AI tools could help ease the burden of ‘datemin’ (dating admin) – the administrative drudgery of dating.

While such functionality could lighten the cognitive load, it also risks further automating intimacy in a context where authenticity is increasingly hard to come by.

Making dating profitable

For all off its “delete us” branding, Hinge is an exponentially lucrative business.

The app generated $550m in revenue last year, according to Match Group earnings- a 38 per cent year on year increase.

Its monetisation model, like many apps in the sector, relies on optional enhancements in the form of premium subscriptions and in-app upgrades.

Still, critics argue that the entire sector suffers from a commercial contradiction – the longer Hinge’s users remain single, the more revenue they generate.

In the US, Match Group is facing a class-action lawsuit alleging that its platforms are “intentionally addictive”, reported The Guardian.

The parent firm was blamed for engineering its apps to maximise engagement rather than outcomes. Yet, the company has strongly denied the claim.

Hinge, for its part, insists that its growth is sustainable – even if its users churn by design.

“What we have learnt is that trust builds long-term value”, claimed Jantos. “Our growth is a function of people telling their friends that it worked”.

Still, the rise of generative AI, coupled with increasingly vocal demands for greater transparency, has amplified questions around identity verification and platform accountability.

Jantos acknowledged the need for adaptability in this “fast-moving” space.

“We tailor safety efforts to each market,” she says, noting differences between UK and US frameworks. “There’s no one-size-fits-all solution.”

Hinge’s evolution

In the UK, Hinge’s evolution is also entwined with an escalating loneliness epidemic among younger demographics.

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), nearly one in four 16-29 year olds in London have reported feeling lonely “often or always”.

That sense of social isolation, amplified by the residual effects of the pandemic and the digital era, has created fertile ground for platforms that promise more than just a virtual connection.

To mitigate its effects, Hinge has launched its $1m global initiative in London for the first time, ‘one more hour’, that finds interest-based community events aimed at nudging people into real world activities.

In its UK pilot, it partnered with grassroots organisers to run its sessions.

“We want people to be spending more time dating and less time doom scrolling”, said Jantos.

However, unlike Bumble, which has expanded into friendship and business networking to broaden its scope, Hinge remains steadfastly focused on romantic relationships—a choice that could either become its core strength or a missed opportunity.