Brits’ living standards drop at quickest pace in over a decade

Brits’ living standards are falling at the fastest pace in over a decade caused by historically high inflation outstripping pay, reveals official figures published today.

Take home pay, accounting for price rises, dropped 2.2 per cent over the three months to April, the steepest fall since 2011, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The figures underscore the scale of pressure households’ budgets are under from a cost of living crunch driven by soaring energy bills, tax hikes and rising petrol prices.

Despite trailing price rises, nominal wage growth of 4.2 per cent “was above the pre-pandemic norm and… will probably give a majority on the [monetary policy committee] the green light to raise bank rate this week,” Martin Beck, chief economic adviser to the EY Item Club, said.

The Bank of England is expected to lift rates by at least 25 basis points to 1.25 per cent this Thursday. Some investors think governor Andrew Bailey and co will go further and hoist them 50 basis points.

Higher rates will tighten the screw on a British economy that is in the teeth of a slump, primarily caused by households cooling spending in response to rampant living cost jumps.

Output has not grown since the first month of this year and contracted in March and April 0.1 per cent and 0.3 per cent respectively.

The cost of living climbed to nine per cent in April, the highest rate since the 1980s, but is forecast to top 10 per cent later this year.

The UK is suffering from higher inflation compared to the US and eurozone due to extreme tightness in its labour market and exposure to European energy prices that have surged since Moscow sent troops into Ukraine.

Analysts have warned strong upward wage pressures caused by tension in the jobs market may result in high inflation being embedded in the economy over the long-run.

Workers tend to demand pay bumps amid price rises, prompting firms to hike prices and, in turn, sparking more pay increase demands. This process is known as a wage/price spiral.

However, today’s figures suggested tension in the labour market may be unwinding.

Joblessness jumped to 3.8 per cent in April and economic inactivity dropped for the first time since last October.

This rise in the number of available workers should, in theory, keep a lid on wage growth by weakening workers’ bargaining power.

“It is possible that this is the very first signs that the weakening in economic activity since the start of the year is filtering through into a slightly less tight labour market,” Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said.

Although easing the inflation outlook, early signs of softness in the jobs market will strengthen fears the UK economy is headed for contraction this quarter and may even tip into recession – defined as two consecutive quarters of contraction – this year.

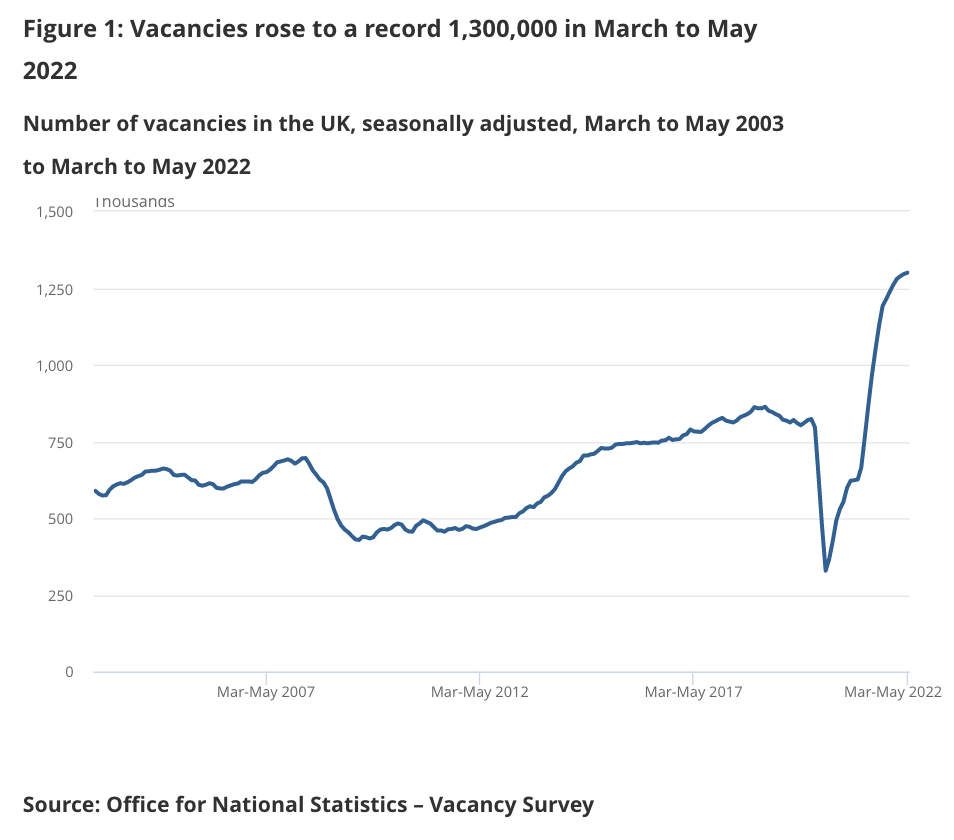

Demand for workers remains extremely strong, with vacancies jumping to another record of 1.3m, while the ratio of vacancies to every 100 employee jobs also remained at a record high over the three months to April.

Businesses are struggling to find workers amid a shallower labour market, prompting them to curb activity. This could weaken UK growth by hamstringing firms’ capacity to step up production to meet demand.

“There is not yet any sign of the economic slowdown affecting the jobs market, but if we don’t address the fact that there are not enough people looking for work, this could put another dampener on the UK’s economic growth,” Neil Carberry, chief executive of the Recruitment and Employment Confederation, said.