Argentina in default: What happens next?

Argentina may be in denial, but pretty much everyone else (including several ratings agencies) thinks the South American country is in default.

What happens next is fascinating, as John Hartley explains for Forbes.

In a show of popularism, the Argentine president, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, claimed on television that the nation was not in default: that it had paid the requisite funds ($539m) to the trustee of its bondholders, Bank of New York Mellon, and that it was the truculence of US judges that had prevented interest payments reaching its creditors, not Argentina.

Argentina may even, according to Bloomberg, have found a way out of default altogether – by posting cheques to intermediaries between BNY Mellon and the actual investors, without having to pay a penny to holdout creditors that did not agree to previous debt haircut deals.

De Kirchner argues that her country wanted to pay its debt – just not to the holdouts, which it thought were seeking to take advantage of Argentina after its last default in 2001.

US judges disagreed and ended a decade-long struggle at the end of June. After a 30-day grace period, Argentina was ordered to pay all bondholders, including the few holding out for payment under the original terms (negotiated the last time Argentina defaulted). Under the so-called pari-passu clause, they said, you can't pay one creditor without paying them all.

New York judge Thomas Griesa froze the $539m in the vaults of New York Mellon.

Argentina's problem, is that 90-odd per cent of bondholders may have agreed to take a haircut on what they were owed when Argentina defaulted in 2001/2, but some didn't. These handout creditors now include the likes of NML and Aurelius Capital.

The payment being claimed by these so-called 'vultures' (NML et al) is only $1.5bn, though, so why not just cough up? This graph explains why Argentina was loath to do so:

On the left is the $1.5bn that Argentina would need to pay NML et al. The problem is that there is a clause (the future offer clause) that says Argentina can't give some of its creditors improved payment conditions without offering them up to everyone.

The $1.5bn goes up to $15bn if Argentina has to pay other holdout investors and $120bn if it has to pay all its creditors at the improved rate. This, it says, is not possible and would bankrupt the country.

Starting to feel sympathy?

There is an argument that Argentina is being hard done by. It goes that if you take a gamble on the bonds of a nation in the throes of a default then you get great rates because the risk is high. You accept that if everything goes wrong you might lose. Taking those rates, losing the gamble and then holding out for the big payday anyway is a bit disingenuous, not to mention sneaky. This argument has been made by Martin Wolf in the Financial Times.

The counter argument is that as a country, you can't call out for help from the global markets, receive it, and then not pay up. Especially because if one country does that then investors may start to see sovereign bonds as less than trustworthy.

Argentina behaving badly

The other issue is that Argentina is not considered to be the most economically transparent nation around. There are whispers that not all bondholders would enforce the conditions of the future offer clause and that if Argentina had negotiated with them, instead of playing a heady game of brinkmanship, the possible payout might have been much less.

What is more, Argentina angered many involved by not engaging in face-to-face discussions with NML until the last possible minute.

Then there is Argentina's other game: many commentators have alleged that the official CPI inflation figures are deliberately lowered, and that GDP may not be entirely accurate either. This doesn't exactly make Argentina a pin-up for investors.

You cans see graphs for the estimated disparity in CPI here.

What's next?

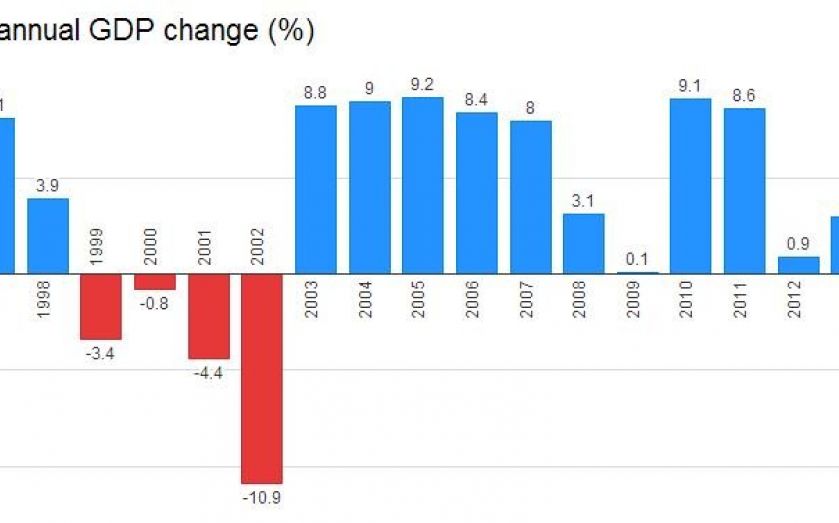

Default for Argentina in 2001 was precipitated by recession as you'd expect, but the 10.9 per cent drop in GDP that followed was brutal. For a country that many people think is running an inflation rate of close to 25 per cent and is overestimating its GDP, a default is not what the doctor ordered.