Anne Stevenson-Yang on China, audit reform and why she’s unsure about Yorkshire

City A.M. sits down with the co-founder of activist short-selling firm J Capital Research to discuss China, its companies and whether they require closer inspection

Where exactly is China heading? It’s a question asked endlessly by senior politicians and business chiefs alike.

Anne Stevenson-Yang knows the country all too well, and, like so many others, is not optimistic about its direction of travel.

China’s economy has failed to properly bounce back from the pandemic and Xi Jinping shows no sign of releasing his perennially tight grip on power.

“I’m afraid I have a fairly dark view,” she said. “Let’s hope it doesn’t just shrink and become a closed, dark kingdom, the way it was in the 1970s.”

Stevenson-Yang started her career in China in the 1980s as a “foreign expert” at a government magazine, before returning in the 1990s with the US-China Business Council, witnessing the ups and downs of China’s economy and politics up close.

She later moved into investment research, however, co-founding activist short-selling firm J Capital Research.

She says she developed investigative skills during her early years working as a journalist – “scraping it together as journalists do”, as she puts it.

“I like finding the gap between reality and reporting, and that’s something that the big banks generally don’t do,” she said.

“There are plenty of people who analyse the published financial statements, but if you can go visit the factories and take pictures of the offices and talk to competitors and things like that, that really provides a difference,” she said.

“There are plenty of people who analyse the published financial statements, but if you can go visit the factories and take pictures of the offices and talk to competitors and things like that, that really provides a difference.”

Anne Stevenson-Yang

In another 2021 interview, Stevenson-Yang said that as a short seller she was primarily motivated by “moral outrage”.

But is that still the case?

“It is… I would really like to make a lot of money too, although that never really happens,” she joked.

Chinese firms

While not exclusively focusing on Chinese companies, her encyclopaedic knowledge of the country and fluent Mandarin are useful assets when it comes to probing Chinese firms.

“Very often, it’s Chinese firms that are reporting more than they really make, so that’s something that we have focused on,” she said.

Stevenson-Yang was one of the first to call out Evergrande, the gargantuan Chinese real estate developer that eventually collapsed earlier this year.

“Evergrande is really the poster child for this property explosion and the property mania,” she said, noting that the future of fellow property developer Country Garden hangs in the balance.

However, there’s one Chinese company that is causing a stir here in the Square Mile: Shein.

The fast-fashion giant, which was founded in China but now headquartered in Singapore, is reportedly preparing to list on the London Stock Exchange.

While a £50bn debut on the City exchange would be a crucial boost for the struggling bourse, claims of poor working conditions in its factories and use of cotton made in the Chinese province of Xinjiang, where thousands of Uyghurs have been detained in Labour camps, has meant not everyone is quite so thrilled by the news.

Stevenson-Yang said that while she understands the impulse to get the company to list here, companies like Shein have, unfortunately, earned the suspicion of investors because “so many companies out of China have turned out to be misreporting their results”.

Audit reform

The dearth of listings in London has sparked sweeping reform efforts in the hope that a series of regulatory changes will breathe life back into the exchange. City minister Bim Afolami famously said that regulators “need to realise that if you’re regulating a market, in any area, there’s no point having the safest graveyard”.

“I mean, I love the quote, but it depends on whether your regulatory focus is on the exchanges themselves, and the companies that are trying to list, or on the individual investors,” she said.

But Stevenson-Yang thinks the way we do corporate audits should not only be bolstered to properly safeguard investors, but completely overhauled.

She proposes that companies should pay into a fund, administered by people like the US Securities and Exchange Commission or the Financial Conduct Authority here in the UK, for example, and then they should audit companies.

Why? “Because the whole incentive for auditors right now is to capture more contracts, not to really complete great audits,” she said.

“The whole incentive of auditors right now is to capture more contracts, not to really complete great audits.”

Anne Stevenson-Yang

Auditors will correctly argue they are not investigators, she said, but “you need some investigators”. However, she is not expecting the idea to be implemented anytime soon.

Visiting the UK

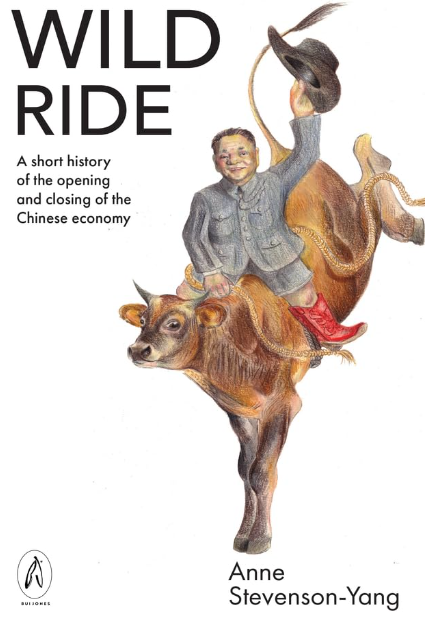

City A.M. spoke with Stevenson-Yang as she passed through London promoting her latest book ‘Wild Ride: A short history of the opening and closing of the Chinese economy’.

She said she first came to London in the 1970s when you could only get “famously beige” English food and “there weren’t a lot of non-white people around”.

“Now, it’s much more diverse, much more interesting… [and] there’s better food,” she said, adding that cities like London and Manchester are great places to visit.

“I’m not quite so sure about, you know, Yorkshire,” she said, however. “I’ve watched too much Happy Valley.”