Academics tried to rank the best of finance Twitter and made three huge mistakes in the process

Two academics have set out to find the best of the best of financial Twitter.

In their new paper, "How to measure the quality of financial tweets", Cerchiello and Giudici note that data from the social network "may be very useful".

They suggest that it could be used to "predict financial tangibles, such as share prices, as well as intangible assets, such as company reputation".

But Twitter can be a confusing and noisy place. The authors suggest that a quality index may overcome these issues.

Sadly, in attempting to create one, they hit three big stumbling blocks along the way.

Bizarre language

It's clear from the off that the writers don't really use Twitter. Firstly, individual users are not called "twitterers", and their plural is not "tweeterers".

That's deprecated terminology at best. "Tweep" or "tweeps" is preferred, while "tweeter" may also be acceptable when referring to a single user.

Language shouldn't be prescriptive, and it's not the specific error that's the problem, but what it suggests. The authors don't seem to be familiar with the platform.

Questionable samples

The authors had to start somewhere, but the list of users they've employed is clearly outdated.

They claim they've used a 2013 Financial Times piece that lists "the top fi nancial tweeters to follow", something a search of the FT's website reveals no results for.

It seems more likely that they've used this list from Financial News, published last May.

Wherever it's from, many names are conspicuously absent from the list, while other accounts that are included are now inactive (EconomistHulk hasn't tweeted since last June).

Methodological nonsense

For all the mathematical talk used in the paper, the rankings boil down to some very crude metrics, with an emphasis on retweets of content.

This is almost as bad an idea as Niall Ferguson's Blogviation index, which assesses the quality of a Twitter user by their followers-to-tweet ratio.

Just as poor users of Twitter often have a large following, as a result of their offline fame, tweets often get a lot of retweets because they included something really daft.

That the users of this paper haven't factored in potential hate retweeting, where messages are shared in order to draw attention to an error or to mock, is another sign that they have little practical experience with the platform.

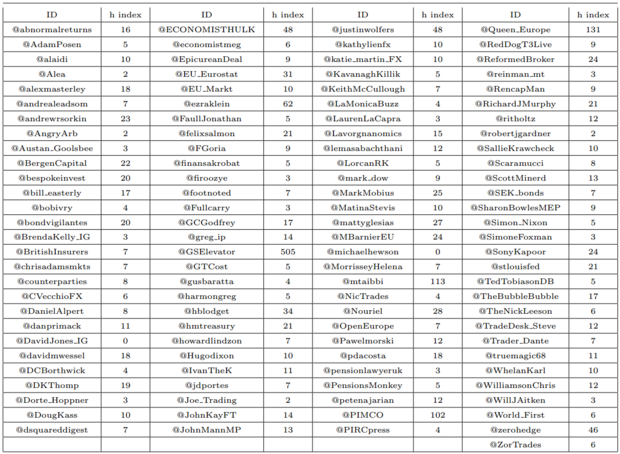

Here's the final ranking, by what the authors call the "H index" of each Twitter account they looked at: